The morning air in Sarachane Square carries a confusing mixture of scents. Tear gas from last night's demonstrations mingles with the aroma of simit, the Turkish bagels sold at every street corner for breakfast. The spots where protesters burned tires yesterday remain visible on the black asphalt, but the square is mostly quiet now, with passersby making their way to work.

Sarachane district, which simply translates to "saddle makers," is one of Istanbul's oldest quarters. The square where demonstrations take place is adorned with an aqueduct built during Roman Emperor Valens' reign – an ancient architectural marvel standing in stark contrast to the massive complex facing it. Istanbul's city hall and municipal services center is an enormous concrete structure inaugurated in the 1970s that once symbolized the city's march from its glorious history toward a modern future. This imposing government building has become the focal point for the massive protests filling the square.

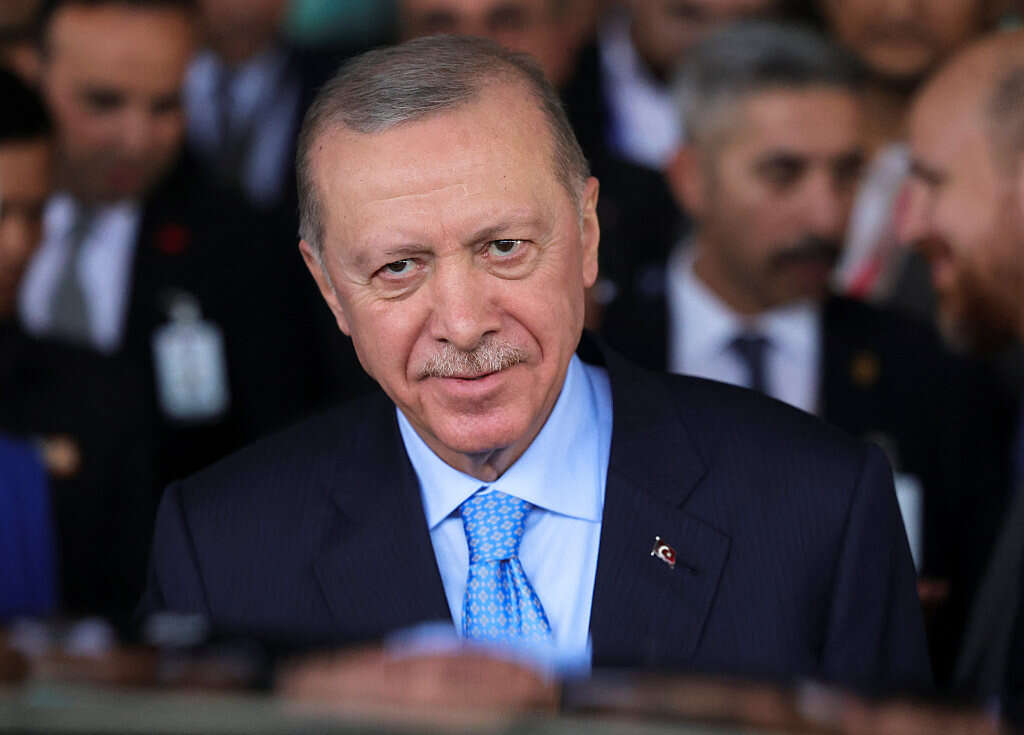

Two protest shifts, continuing through the night hours, stand near the building where Ekrem Imamoglu worked as Istanbul's mayor before his arrest. Imamoglu is the main rival of the country's president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The first group comprises black-clad, masked teenagers – supporters of the Besiktas soccer team who have aligned themselves with protesters demanding the opposition leader's release. These young fans shout patriotic slogans at full volume, some dating back to Mustafa Kemal, Turkey's legendary leader who transformed the country from a defeated religious empire into a proud, secular nation-state.

The black-clad patriots' chants gladden another group of protesters – middle-aged women wearing expensive clothes who have also remained at the site overnight, trying to keep the protest spirit alive. One approaches the young people and offers them and me warm pastries – a peculiar fellowship of protesters at odd hours. Selen, a protest activist among these women, explains why they stood in the cold night calling for Imamoglu's release: "It's not just him behind bars; we're all in a kind of prison because of the government's conduct." Minutes later, she and the other women depart for their workplaces, promising to return to the square in the evening with the masses.

Ekrem Imamoglu, whose arrest has become the rallying cry of the Turkish opposition and whose portrait now adorns the square, resembles a polite, smiling bank clerk more than an opposition leader who fills the government with fear. Yet, with his conciliatory approach, traditional background, and dedication to transparency and rule of law, Imamoglu has managed to defeat Erdogan's candidates in three consecutive mayoral elections. According to some national polls, he stands a chance of defeating the Turkish president in a head-to-head contest. That's precisely why the ruler in Ankara understands that the battle for Sarachane Square could easily transform into a battle for his very rule, and his loyalists are responding accordingly.

Turkey's interior minister, Ali Yerlikaya, announced earlier this week that 1,418 protesters have been arrested since the protests began. Some were detained in their homes after facial recognition cameras identified them at demonstrations. Others were arrested merely for criticizing the Erdogan regime on social media. It's no wonder that protesters repeatedly express their fear of living in what they describe as a "prison of thoughts." The prospect of being arrested in one's home simply for participating in protests – or even expressing support for the movement – dominates the fears of young demonstrators while simultaneously spurring them to action.

On the other side of this divide, in a small café meters from the square, a group of young police officers sit in late morning, smoking cigarettes, drinking tea, and eating breakfast, ignoring accepted Ramadan customs. One officer named Osman invites me to join them. He seems eager to defend the honor of those in uniform: "We would never attack our own people; you'll see for yourself. People are free to protest and be angry and speak, but there are a few who choose violence, and we have no choice but to deal with them." Osman is a municipal police officer whose regular duties involve maintaining public order, not riot control. "I have quite a few friends and family members who go out to protest; these aren't strangers to me," he insists while holding his small tea glass.

Echoing familiar voices

The further one moves from the protest epicenter, the more Istanbul – that mighty, cosmopolitan, tourist-friendly metropolis – seems to continue its normal rhythms, at least on the surface. Near the Hagia Sophia mosque, tourists gather to marvel at the historical wonders of the ancient city, while shops and food stalls overflow with goods.

"Don't be fooled; it's a beautiful day outside, so the street looks nice, but we've taken a hard hit here," says Ferhat, who owns a small restaurant not far from the historical heart of the city. "First the inflation, then the lira crash two years ago – I lost a lot of savings. And now the number of tourists has dropped to almost zero; it breaks my heart," he laments. When I ask if he supports the protests, his eyes immediately light up. "Of course, there's something so basic here – defending the rules of the game. If someone who was democratically elected can be arrested, then we can all be arrested. We cannot allow that," he says passionately.

On Istanbul University's campus, just hundreds of meters from the protest epicenter, classes continue normally. Students in the nearby café hesitate to speak with a foreign journalist – they've learned that even small comments in the wrong place could lead to arrest. Eventually, the reporter is invited to join a table where students discuss the political situation in English.

Zeynep, a young marine biology student wearing a hijab who came to Istanbul from Anatolia, expresses frustration with the government. "They don't care about us in any way. I saw the neglect in my hometown. While Erdogan built himself a palace, my parents struggled with inflation and wage erosion. Every time something inconveniences them, they change the rules – this arrest exemplifies that," she says.

Elin, sitting nearby, defends the government: "I don't understand the fuss. There were elections recently, and this is what people chose." The discussion echoes familiar political debates. "People also voted for Istanbul's mayor – that's exactly the point," counters Johnny, who willingly identifies himself. "When convenient, it's democracy, when it's not – everyone should be quiet." Minutes later, the group shifts to discussing "The White Lotus," and the amused reporter continues on his way.

Rights, law, justice

As twilight falls on Sarachane Square, protesters begin streaming in. Religious demonstrators hold their Ramadan iftar meal on the grass in the adjacent park, while secular protesters smoke cigarettes and buy souvenirs from omnipresent vendors who've quickly adapted their merchandise to the movement. Near the local government building's entrance, protesters have already gathered.

The reporter meets Asla, Tuba, and Jiran – three young female students who traveled from the suburbs for their first-ever protest. "You'll see all shades of Turkey here – secular, religious, elderly, students. We can't allow this to become our country's future. We must win this struggle."

Near the stage where the Republican People's Party leader will soon speak, older protesters have gathered. Some wear party pins, appearing more like retirees on an outing than participants in an existential struggle for their nation's future. When one hears English being spoken, he approaches with a serious expression. Though he knows no English, Ahmet Akci, an Istanbul pensioner, uses Google Translate on his smartphone to communicate. "I don't like what this country has become in recent years," he types.

Unlike younger protesters, Akci freely shares his full name. "Erdogan just quarrels with everyone – the opposition, the world – meanwhile, our cities are dirty, everything is expensive, and our best young people, like my grandchildren, seek jobs abroad," he writes. As our unusual digital conversation continues in the bustling square, he touches on foreign relations: "I don't understand why we must quarrel with Israel. Want to help Palestinians? Fine. But we'd have more influence with Israel if we weren't constantly arguing with them," he notes through the translation app.

During this conversation, the square has filled dramatically as waves of people emerge from the nearby metro station, which reopened after days of closure imposed by the governor, a staunch Erdogan supporter. The atmosphere transforms with these fresh arrivals, taking on a carnival-like quality. Thousands of young people arrive wearing various masks – evidence of their fear of police surveillance cameras. The rallying cry "Law, rights, and justice" dominates, appearing on numerous creative signs.

"Yes, sex is great, but rights, law, and justice are the best," reads a sign carried by Inara, a young protester attending one of her first demonstrations, with surprising seriousness. "A good slogan attracts attention, and it's nice to get looks from guys for being bold, but our situation is so difficult that no joke really helps," she explains.

Dinosaur in the square

The protesters have embraced another satirical theme: an abandoned dinosaur-themed amusement park where financial irregularities were discovered during construction. The park was built by an Erdogan associate, and the president himself attended its grand opening in Ankara. Beside a sign reading "I also escaped from Erdogan's park" stands Ana, a 23-year-old student in a dinosaur costume that draws chuckles from passersby.

Atas, Ana's partner, expresses grave concern for his fellow protesters. "I've been here daily since the protests began. From the start, they tried to suppress this movement, but so many people came that the police adopted new tactics. They let people 'blow off steam,' gather and give speeches, and then they charge, beat, and arrest. My friend was arrested and beaten until he nearly lost consciousness," he says, visibly worried. Looking directly at the reporter, he pleads: "Promise me when the speeches end, you'll get out of here. The police are coming to kill us; they don't care if we die." His words land with shocking force, impossible to reconcile with the friendly policeman's morning assurances.

The paranoia among some protesters is palpable. On the demonstration's edges, young people don protective vests and face coverings, preparing for confrontation. The reporter photographs a young man wearing a "Grey Wolves" armband – a nationalist, antisemitic movement that previously supported Erdogan but has splintered, with some violent supporters joining the protests.

This proves to be a mistake. Within moments, several large men surround the journalist, demanding in broken English that the photo be deleted. Though the reporter complies, one man grabs the phone. "What the hell, brother," he says, noticing unfamiliar text. Thinking quickly, the reporter claims, "It's Navajo, a Native American language." The men look confused. "You Indian?" one asks clumsily. "Brother! We're not called that anymore. It's not cool. It's not right," the reporter responds, leaping to defend his invented heritage.

The men nod in agreement, and the phone is returned with an apologetic look. As the reporter begins walking back toward his hotel, stun grenade explosions sound from the square's northern edge. Families with children, elderly people, and casual protesters head toward the metro station while masked youths continue arriving, beating drums and shouting battle cries. The reporter decides against witnessing the imminent clash – an Israeli journalist's arrest in Turkey would be problematic even for someone accustomed to conflict zones.

Power is still with Erdogan

"I really hope you're not eating at Burger King or something like that," says Anwar (pseudonym), an Istanbul-born businessman, in a reproachful tone as the reporter joins him at a café overlooking the Bosphorus Strait. The culinary patriot seats his guest at a table loaded with traditional Turkish breakfast delicacies after thoroughly interrogating him about every meal consumed during the Istanbul visit.

They last met in the border town of Silopi in 2015, after the reporter's return from Iraq during the final stages of the anti-ISIS campaign. Anwar remains sharp, energetic, and patriotic, but one thing has changed dramatically: once a prominent member of Erdogan's Justice and Development Party who prospered in eastern Turkey through government connections, recent years have completely transformed his political outlook.

The serene waterfront café atmosphere contrasts starkly with the previous night's protest scenes, yet Anwar's words echo the same frustrations: "You can't prosper without a functioning legal framework. Turkey's legal framework has become a hollow shell. Corruption and nepotism have always existed here, but slowly everything else that worked has disappeared," he explains with evident concern.

The businessman recalls his years supporting Erdogan: "This man transformed Turkey from a poor country into a regional power, especially economically. My children were born into a hopeless Turkey where the military interfered in politics, and national pride was at rock bottom. The Justice and Development Party brought industry, infrastructure, and a world-class airline. I live secularly, but their religiosity didn't bother me because I saw people committed to Turkey's success."

When asked what changed, Anwar sighs: "Remember when we met in the east and you asked if I feared ISIS? I told you they had no chance against Turkey. Indeed, ISIS collapsed, and internationally, Turkey is stronger than ever. But internally, Erdogan fragmented our society. The gaps between secular and religious, rich and poor, have never been wider. The government pushed religious institutions everywhere, and if you were not in those circles, you no longer mattered. No wonder both left and right are dissatisfied," says the formerly optimistic man, now visibly disheartened.

"Three days ago, I did something unprecedented in my life," Anwar confesses. "I joined a protest. I left my family at home and went alone to Sarachane Square. I never imagined protesting alongside Republican People's Party members, but it was the first time I'd breathed freely in three years. Seeing young people with that determination in their eyes, knowing our country has a new generation willing to fight for it – it gave me hope."

Despite his emotional connection to the movement, Anwar's political analysis remains coolly pragmatic: "These protests are merely a show of force; they won't topple the government alone. The scales haven't decisively tipped toward the opposition, but Imamoglu's figure could unite them in a way that brings Erdogan's defeat in future elections, even if Ekrem remains imprisoned."

Having met Imamoglu several times, Anwar explains the opposition leader's appeal: "True, he resembles Harry Potter – this good boy image – but his charisma is undeniable. He's honest, hardworking, and accessible. His determination is extraordinary. I'm certain that despite his imprisonment, he's already planning a hundred moves ahead," he says with a knowing smile.

Returning to Sarachane for another evening of protests, the reporter contemplates Imamoglu's portrait. One can't help wondering if Turkey has finally found its hero who will free it from the Justice and Development Party's grip and lead it toward a better future – one distinct from Erdogan's Ottoman imperial dreams. Or whether, like the Gezi Park protests and subsequent opposition movements, this revolution too will fail to achieve meaningful change.