For an archaeologist, uncovering the lost tomb of a pharaoh is a career-defining moment. But finding a second tomb in the same research expedition? That's the stuff of dreams.

Last week, British archaeologist Piers Litherland announced what he called the discovery of the century: The first rock-cut pharaoh's tomb uncovered in Egypt since Tutankhamun's in 1922.

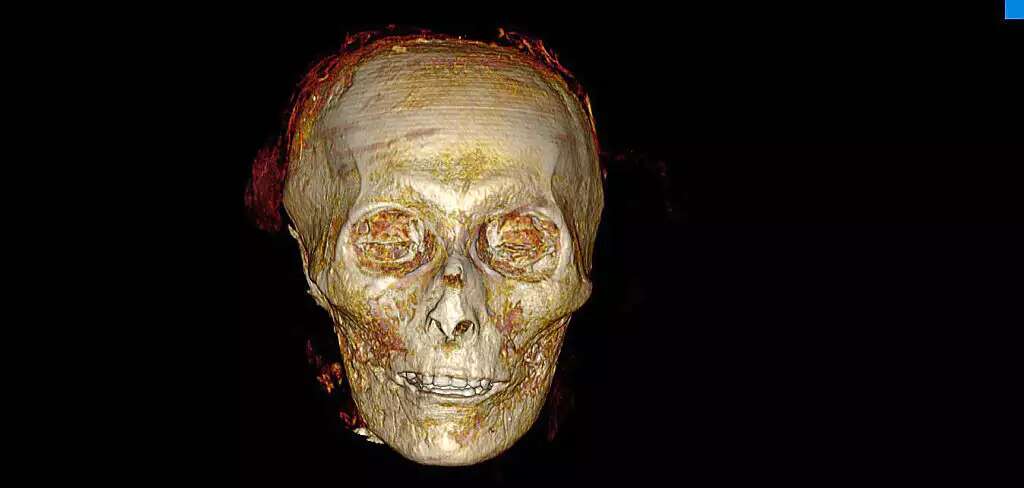

His team located the burial site of Pharaoh Thutmose II beneath a waterfall in the Theban hills of Luxor, a few miles west of the Valley of the Kings. The tomb was found almost completely empty except for debris. Researchers believe it was flooded and looted within six years of Thutmose II's death in 1479 BCE.

Now, Litherland has told The Observer that he believes he has identified the location of a second tomb belonging to Thutmose II—one that he suspects still contains the young pharaoh's mummified body, along with the burial treasures typically entombed with Egypt's ancient rulers.

Archaeologists believe this second tomb has remained hidden for 3,500 years, buried beneath 23 meters of limestone flakes, rubble, ash, and mud plaster, making it indistinguishable from the surrounding mountain.

"There are 23 meters of man-made debris piled over a specific point in the landscape where we believe, based on corroborating evidence, that a burial monument is concealed beneath these layers," Litherland said. "Given the scale of effort involved, the best candidate for what lies beneath this massive heap is Thutmose II's second tomb."

While searching near the first tomb for clues about where its contents might have been moved after the flood, Litherland discovered an Egyptian memorial inscription buried in a pit alongside the remains of a sacrificial cow. The inscription suggests that the burial goods were relocated by the pharaoh's wife and half-sister, Hatshepsut—one of Egypt's greatest rulers and among the few women to govern in her own right—to a second, as-yet-undiscovered tomb nearby.

Researchers are now attempting to tunnel their way toward the burial chamber, but massive boulders and unstable layers of rock pose a significant risk to the excavation team. Progress has been slow, requiring workers to carefully dismantle the rocky layers by hand.

For Litherland, whose fascination with ancient Egypt began in childhood, a month of manual labor is a small price to pay for the chance to uncover Thutmose II's final resting place. "For me, it's like a dream—like winning the lottery. I never imagined this would happen to me," the archaeologist admitted.