Climbing the paths leading to the summit of Gellert Hill is no simple task on January mornings. Though we're ascending on a day that isn't particularly cold by Central European standards, the ground is covered with a thin layer of ice that accumulated during the night, causing members of our group to occasionally slip. At some point, these falls become a semi-comical and semi-bonding activity. Eventually, we all arrive safely at the peak to discover that the panoramic view entirely justifies the effort.

Dr. Yoav Sorek gathers us and begins explaining what we're seeing. Unlike the vast majority of Israeli tours in Budapest that focus on the Holocaust period before moving on to the Communist years and ending with the present day, Sorek takes the group 150 years back in time. He speaks about Austria-Hungary – the powerful kingdom that existed until World War I – and about the unique development of Hungary's magnificent Jewish community, a chapter that has been almost entirely pushed aside and forgotten from Jewish history. The names of influential and important rabbis who somehow escaped the spotlight of consciousness float in the air. Chief among them is Rabbi Moshe Shmuel Glasner, the hero of Sorek's doctorate – a figure who, had he not encountered fierce and uncompromising hostility, might have changed the fate of the country's Jews. It's evident that our tour guide is determined to restore the lost honor of Hungarian Jewry, and the horizon-expanding explanation we're hearing on this beautiful hill overlooking the Danube is just one way to do so.

"While writing my doctorate, I fell in love with Hungary's story and its symbiosis with the Jews," Sorek explains to me later. "For me, it was a lost and fascinating continent. I found a story about a culture that arose and revived itself in national awakening, and within it embraced the Jews, who in turn saw it as paradise. Add to that the good relations that exist between the peoples to this day, and I find it fascinating."

Many Hungarian natives live in Israel, but Hungarian culture has been marginalized and barely exists, certainly in Religious Zionism. Why?

"I have a theory that I can't prove. Many in Religious Zionist circles have Hungarian roots, but when looking at this movement's history in Israel at the institutional and consciousness level, we see that in the first generation there were Yekes (German Jews), then Jews from Russia and Lithuania, like Rabbi Moshe Zvi Neria and Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, while Hungarians only became Zionists en masse after the Holocaust. Many survivors immigrated to Israel, so Religious Zionism has a strong Hungarian foundation, but it lacks an ethos and figures. What people know about Hungarian Jewry is mainly connected to Satmar, meaning the zealots. There is a zealous element in Hungarian Judaism, but it certainly wasn't the majority."

A Coup is Just an Excuse

Israelis love Hungary for its cost of living - because it is the opposite of Israel's. Even in kosher restaurants, typically one of the most expensive aspects of traveling abroad, you won't pay more than 120 shekels per person for a full meal, including dessert. Western brands in malls and shops will cost you almost the same as in Israel, but local brands are much cheaper. To calculate the cost, take the price in Hungarian Forint, remove two zeros and subtract another 10%, and you'll have the amount in shekels. 10,000 Forint, for example, is about ninety shekels. This calculation seems complicated at first but will become second nature after your fifth bottle of water.

In the historic city center, near the Great Synagogue, there are two relatively high-quality kosher restaurants: 'Hanna' and 'Carmel'. Right next to them, two cafes and several fast food stands together provide kosher infrastructure for a few days' stay in the city. In the restaurants, you'll find goulash and nokedli, symbols of Hungarian cuisine, which is based on meat, potatoes, and eggs. Or as my Hungarian grandmother often said, "to be satisfied, you don't need to complicate things."

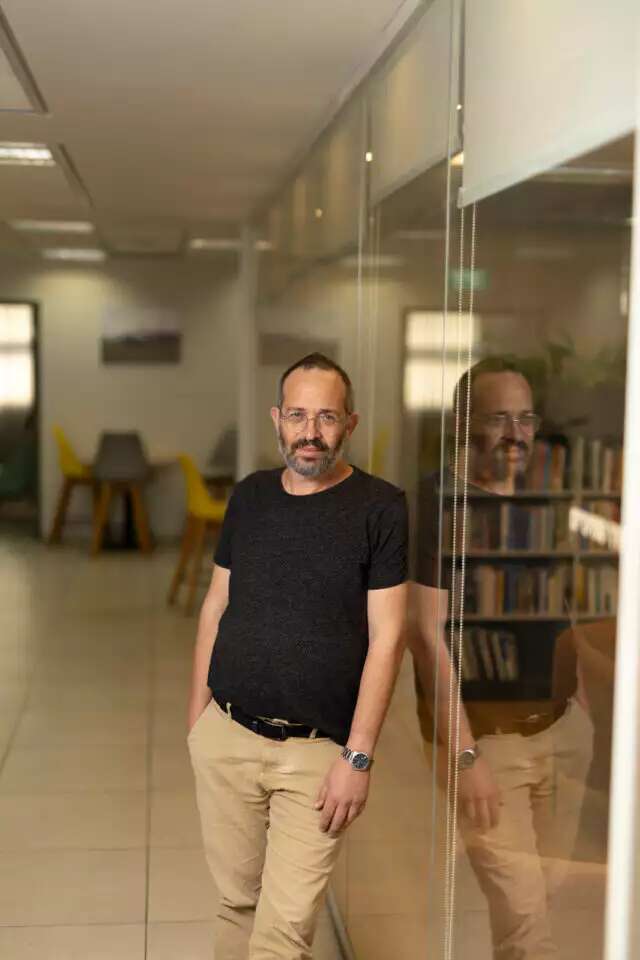

Over a steaming bowl of goulash at one of the kosher restaurants, I sit with Shorek to hear how he rediscovered the history of Hungary and its Jews. He is one of the well-known intellectual figures in the religious-Zionist sector in recent years. Among other things, he founded and edited the 'Shabbat' section in Makor Rishon, and the journals Segula and HaShiloach. Today he is the chairman of 'Lechatchila - A Home for Israeli Torah.' His connection to Hungary seemingly begins at home: both his parents were born in this country. His mother was orphaned during World War II, immigrated to Israel at age five, and grew up in Youth Aliyah institutions. His father was eight when he arrived in Israel on an illegal immigrant ship. "Hungarian culture wasn't celebrated in our home," he recalls. "My parents spoke Hungarian only when they wanted us not to understand something, or when communicating with the previous generation, and when I was 14, that entire generation was no longer alive."

What led you to delve deeper into the history of Hungarian Jewry?

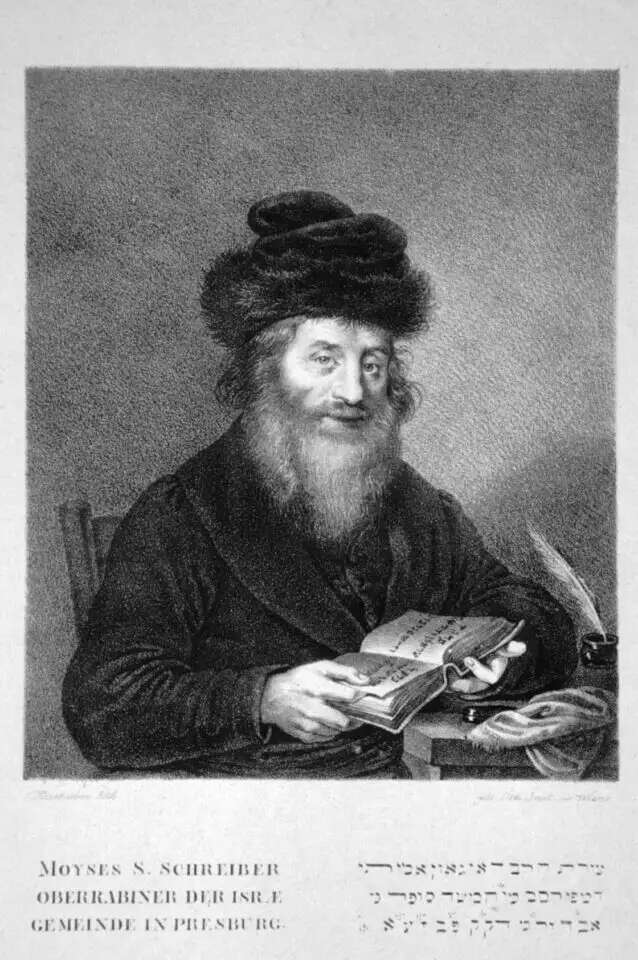

"Both of my parents' families are rabbinic dynasties with long genealogical lines. A kind of elite, if you will, especially on my mother's side, where you find disciples of the Chatam Sofer (Rabbi Moshe Sofer, one of the greatest Jewish legal authorities of the 19th century and a leader in the fight against secularization and reform). They also had an indirect family connection to Rabbi Glasner, but I never heard his name in my childhood.

"I had a certain interest in Hungarian rabbis out of simple sentiment, but I didn't expect to find among them someone who wrote in the style of Rabbi Kook or Rabbi Reines. At one point, I traveled to the US and was invited to the home of distant relatives named Glasner. We descended upon them with seven children for the first days of Sukkot, in the home of a relatively small family. They asked what I was doing, and I said I was about to write a book about the renewal of Torah in Israel. The host got up and pulled a small bound booklet from the shelf: a collection of Religious Zionist thought, an offprint from a forgotten book of the Rabbi Kook Institute published in the 1960s. This section, translated from German, was called 'Zionism in the Light of Faith,' and its author was Rabbi Moshe Shmuel Glasner, the host's great-grandfather."

Sorek began leafing through the booklet, reading and becoming excited. "I was even shocked. I realized that the author of this text was a distinguished Torah scholar who had confidence and broad shoulders, and what he wrote was in some ways exactly what I was supposed to write in my book. He states, for example, that the Torah of exile must make way for the Torah of the Land of Israel, and that there's no place for separation between Orthodox and non-Orthodox. You see things that Rabbi Kook wrote from depth and complexity, Kabbalah and literature, and with Rabbi Glasner everything comes from simple rabbinic intuition. These two figures came from completely different places. Hungarian Orthodoxy was a world unto itself, and Rabbi Kook came from Lithuania and had strong connections with the Hasidic courts around him. They lived more or less in the same period, and more or less the same number of years. They even met briefly in Jerusalem and had previously exchanged some correspondence.

"Rabbi Glasner says things simply. You read something written a hundred years ago, but anyone with a bit of Torah education will understand it as if it were written yesterday. The impressive rhetorical ability, the clarity of thought – all this made me fall in love with Rabbi Glasner's character. I told myself that if one day I pursue a doctorate, and want to study a subject seriously and dig into it completely – I'll choose him. And indeed, a few years later that's what I did." The doctorate Sorek wrote in the History Department at Ben-Gurion University became the book "From Pressburg to Jerusalem" (published by the Zalman Shazar Center). "It took some time to convince the advisors that this unknown figure warranted a doctorate. Initially, it was agreed that the topic would be 'Rabbi Glasner and His Era,' but I'm sure that in the end they too understood that he could carry the work on his own."

Before we get to know Rabbi Glasner, what actually distinguishes Hungarian Jewry from other diasporas?

"First of all, it was a very large community. A significant portion of European Jewry in the 19th and 20th centuries was Hungarian Jewry. It included about a million Jews around 1900. In Budapest alone, about a quarter million Jews lived then – making it the largest 'Jewish city' in Europe after Warsaw. This is a very important community, but it hasn't received the honor it deserves in history and public consciousness. Not much has been written about it, not much research has been done, and therefore not much is known about it. The reason is that Hungarian Jewry was somewhat insular, outside the general European-Jewish discourse. This is the only country that had both Western European Jews, what's called 'Oberland,' German-speaking and educated people, and on the other hand Jews from Galicia and Moravia, the 'Unterland.' In other words, within the same space there are very different Jewish cultures – people who dress differently, eat different food, barely intermarry with each other."

"Secondly, Jews in Eastern Europe were then engaged in struggles between enlightenment and orthodoxy, Zionism and anti-Zionism, socialism and nationalism. Jews in Hungary had an exceptional symbiosis with Hungarians, and most importantly, they had it very good. Therefore, other Jews in the world simply didn't interest them. They conducted their own internal conversation, in Hungarian."

Speaking of Hungarian, you write that it's the only European language that can still be heard today in Hasidic concentrations around the world, besides Yiddish of course.

"That's right. In Brooklyn and Williamsburg, you can still find elderly Jews speaking Hungarian. Among the ultra-Orthodox, you won't find people speaking Russian, Polish, or Czech, because these are languages of those who want to assimilate. Hungarian, on the other hand, wasn't perceived as threatening or leading to too deep integration with the Hungarian people – partly because it's a relatively small nation, but mainly because Jews didn't see Hungarians as enemies. Hungary gave the Orthodox the security that no Reform Jew would bother them or undermine them. This was an emancipation deal that recognized Orthodox Judaism as another 'official church' in the country. And unlike other European countries, which along with recognition demanded that we reform Judaism a bit – to be less xenophobic, more liberal, to allow mixed marriages – here exactly the opposite happened. The state stood behind Orthodoxy and said: speak Hungarian, study Hungarian core subjects, but other than that, do what you want."

Why did this happen specifically in Hungary and not in other countries?

"The nationalism that developed in Hungary before World War I was multi-ethnic and liberal by definition. This stemmed partly from the fact that Hungarians themselves aren't homogeneous. Not all are Catholic, there's a strong Protestant element, so religious tolerance existed from the start and this influenced attitudes toward Jews. A reporter from the Jewish-American Forward who arrived in Budapest in 1910 reported that this was the true paradise for Jews. And we're talking about a journalist coming from the US, the 'golden country.' Another important factor: the Hungarians needed Jews numerically to stand against the Romanians, Slovaks, and Serbs. The kingdom ruled over many other peoples, and Hungarians were only 45 percent of the population in its territory. The Jews gave them the percentage points they needed to be a majority."

This golden age ended after World War I. "Two-thirds of the territory no longer belonged to Hungary, and in the remaining third, there was a Hungarian majority or Jews. Jews suddenly became a minority that could be hated, and 'paradise' became the first place in Europe to establish quotas for Jewish students in universities. They connected it to the Communist revolution that Bela Kun, who was Jewish, tried to lead, but that was just an excuse. However, it's important to say that between the World Wars, Hungary didn't turn into an antisemitic monster. Jews still had a central place in the country, but they were already hated, and antisemitism began to develop where it had barely existed before."

A congress that's a trap

To talk about Rabbi Glasner, we need to go back to the years before World War I, and away from Budapest to Transylvania – today in Romania, but then part of Hungary. The central city in the region was called Klausenburg, today Cluj. "The state authorities cultivated Klausenburg as a center of Hungarian culture. In 1906, for example, they built the Hungarian National Theater there. You can see this building in today's Cluj, but now it's called the Romanian National Theater. It's amazing to see that even a hundred years after Klausenburg became Romanian, the tension between the two sides still bubbles there. You barely need to scratch the surface for it to show. You say a word in Hungarian on the street, and suddenly a resident hugs you like you're their lost brother because they feel like a persecuted minority."

And there, in Klausenburg that wasn't yet Cluj, Rabbi Moshe Shmuel Glasner served as the city's chief rabbi for a very long time – 44 years. "He was an opinionated, rational personality with a modern spirit. His father, Rabbi Abraham Glasner, was one of the important students of the Ktav Sofer (son of the Chatam Sofer) and was married to the Chatam Sofer's eldest granddaughter. The father delivered his sermons in fluent German, meaning clearly 'Oberland,' like most of the Chatam Sofer's family. They weren't zealots at all, contrary to their reputation."

"After serving in a small Hungarian town, Rabbi Abraham Glasner was appointed rabbi of Klausenburg, then a growing Jewish community. He served in the position for 17 years, and after his passing, the community appointed his only son, Rabbi Moshe Shmuel Glasner, in his place. This happened in 1878. There were also opponents to the appointment – the more modern elements in the community, Jews who would later establish the Neolog movement. They said, 'Who is this young man who goes around with the Hasidic rabbis?' Rabbi Glasner was connected to several rabbis from the area, and therefore was a thorn in their side. The ultra-Orthodox, who became angry with him later on, always mentioned that in his youth he was connected to Hasidic courts, meaning to the good ones. Oberland from home, Unterland from the surroundings."

Rabbi Glasner began serving as the rabbi of Klausenburg at a very young age – a position he would resign from after four and a half decades, following disputes that erupted over his Zionist leanings. "At first, he established a yeshiva and was appointed to the Budapest Rabbinical Council, making him part of the Orthodox establishment. He was also a great expert in the laws of ritual slaughter, as befitting a rabbi of a large city in those days, and maintained good relations with rabbis in the area, even though he was somewhat of a modernist. He often traveled to Budapest for communal affairs and published his opinions on various contemporary issues. His responses reveal the character of a bold and unpredictable person, who often thought differently from the rabbis around him."

In what areas was this expressed?

"Around 1900, when he already had twenty years of experience, Rabbi Glasner spoke out on matters of civil marriage, conversion, and other issues that were then at the center of debates, and his statements are quoted to this day. In a new book by Yeshivat Har Bracha on the topic of conversion, there is an extensive section about Rabbi Glasner, who broke new ground and presented a very important position. Basically, he said that once a woman chooses to abandon her Christian identity, we are less concerned with which commandments she observes: her choice is sufficient for us to accept her conversion as authentic, because she is willing to pay a heavy price for it."

When did Rabbi Glasner's not-taken-for-granted romance with Zionism begin?

"The moment Herzl's 'The Jewish State' was published, around 1896. I discovered this in a way that might suggest there were those who sought to diminish his character. These things appear in the manuscript of his book of responsa. The entire book was printed word for word, except for one response that wasn't printed. I discovered this when I was looking for something else related to a printing error, and for that purpose, I compared the printed book to the manuscript, and had already gone through all of it."

"In the omitted question, a rabbi of one of the communities wrote to him: 'They established a Zionist association in the city and want me to be an honorary member, what do you think?' Rabbi Glasner answered: 'You're probably hesitant because they think about nationalism and not about religion, but ultimately Zionism strengthens people's religious identity, brings them closer to Judaism and the Land of Israel, and distances them from assimilation, and this is a wonderful thing. They say they're not interested in the religious aspect? So they say. The very fact of their choosing religious identity in an era when it's so easy to escape from it, this is the 'beginning of redemption.'' He actually used this term, before the year 1900. I don't know if anyone else in Europe said these words then."

And then came the clash with Hungarian Orthodoxy.

"The first world congress of the Mizrachi movement took place in 1904 in Pressburg – today Bratislava, capital of Slovakia. Rabbis in Hungary organized to boycott the event, and that's where Hungarian Jewry's anti-Zionism was born. It didn't have deep roots; it was a political move against Mizrachi. Rabbi Glasner wasn't part of the boycott: on one hand, he apparently respected it and didn't personally attend the congress, and on the other hand, he published a letter against the boycott, which he said was done without serious discussion and based on false assumptions about Mizrachi. He himself became Mizrachi's representative in Hungary, though at that stage it had no practical significance. Later, around 1920, he gave many lectures and swept all of Transylvania into Zionism, but in 1904 there was no one in Hungary to talk to about the subject. Rabbi Glasner understood there was no point, didn't preach about Zionism, didn't write articles, and didn't advocate. Because Hungarian Jews simply weren't there. As mentioned, they had it good in Hungary, and they didn't want to be considered unpatriotic."

Did Hungarian Jews' anti-Zionism stem from extreme religiosity or rather from Hungarian nationalism?

"The public didn't flock to Zionism because they identified with Hungarian nationalism, and Zionism in their view contradicted all that. By the way, Rabbi Glasner was a Hungarian patriot and didn't see Zionism as contradicting this. During World War I, he wrote that it is forbidden to use tricks or 'get sick' to dodge military service, and his son even served as an officer in the Hungarian army. The Hungarian rabbis who led the sharp opposition to Zionism were heavily influenced by propaganda from the 'Black Bureau' in Kovno, which came from the Chabad Rebbe's study hall, the Rabbi of Brisk, and other Russian rabbis who feared the danger of secularization. Hungarian Jews weren't very interested in this because there was no secularization there: you were either religious or assimilated. But in Eastern Europe, secularization was strong, and in the eyes of the rabbis there, Zionism was a way to be Jewish without religion, and it had to be fought against relentlessly. That's why they were shocked when they learned that a Mizrachi conference was going to be held in Hungary, and that the rabbis there didn't understand it was a trap aimed at secularizing everyone. This propaganda was very successful with important rabbis who already had an ultra-Orthodox sentiment, in the sense of fearing anything new. There were quite a few rabbis in Hungary then who thought differently and saw Zionism as wonderful, but they were silenced."

Looking back, it seems Rabbi Glasner's view was quite naive, and the ultra-Orthodox concerns were justified. Most Zionists today are secular, and the Jewish state is secular.

"I disagree with that statement. Mass secularization occurred in Eastern Europe without any connection to Zionism. For those who became secular, Zionism was actually the more Jewish option, instead of becoming Communist-Socialist or just going to America and being secular Jews. Thank God, a large enough part of the Jewish people chose the Zionist path."

Herzl didn't say

The Jewish community here is relatively small, but echoes of its magnificent past are evident in almost every corner. The impressive Neolog synagogue on Dohány Street in Budapest is considered a must-see attraction for tourists from around the world, regardless of their religion. I ask Sorek to talk about these echoes of the past. "The sharp division between Orthodox and Neolog Jews continued to exist in Hungary, both formally and practically, until the Holocaust and even after," he explains. "In the late 1940s, Orthodox synagogues and educational institutions operated in Budapest. Following waves of emigration – after the war, and again in 1956 – and due to the Communist regime's hostile attitude, almost no Orthodox Jews remained in Hungary. But the community officially continued to exist and maintained many properties, even if deteriorating."

One of the interesting proofs of Orthodox Judaism's decline in Hungary can be found in Chabad's central role in everything related to Judaism in the country today. "We classify Chabad members as ultra-Orthodox, and this Hasidic movement was even anti-Zionist, but dividing Jews into Orthodox and non-Orthodox is completely foreign to Chabad thinking. It's a movement that seeks to reach every Jew, and in the diaspora, it's even an Israeli anchor."

Chabad's activity in Hungary in recent decades operated alongside the dwindling Orthodox community, and sometimes there was hostility between the sides. All this changed recently when a person associated with Chabad became the official manager of the community and began a long and fascinating journey to renew its assets and shake off the accumulated dust. He raised enormous sums to restore the Orthodox synagogue on Kazinczy Street and began implementing the project. Simultaneously, he's establishing a museum in the community building's basement that will tell Hungarian Jewry's story from the Orthodox perspective, competing with the famous museum of the Neolog synagogue.

Participants in Sorek's tour get to enter the Kazinczy synagogue, still closed to the public, and also visit the real treasure, at least in history lovers' eyes: an archive in the making that seeks to organize tens of thousands of books, certificates, sacred objects, and documents that accumulated in Orthodox community warehouses and were neglected for decades. These materials come not only from Budapest but also from provincial cities, most of whose synagogues closed in the Communist regime's early years.

I ask Sorek why he presents Hungarian Jewry through Budapest, even though Rabbi Glasner, a central figure in the story he weaves, operated mainly in Klausenburg. "When my book was published – almost three years after completing the doctorate – I thought a launch event is nice, but we could do something cooler: a launch journey. I built a tour composed of Budapest and Cluj, and half the participants were Rabbi Glasner's family members, who were very involved in the book's writing process. Seemingly, why not just visit Cluj, his city? The answer is that you can't understand his story without understanding the Hungarian-Jewish story. Budapest doesn't need Rabbi Glasner, but Rabbi Glasner needs Budapest. The Orthodox community was created in this city. Hungarian liberalism enabled the idea of a separate Orthodox community, and the strong symbiosis between Hungarians and Jews caused Zionism to be delayed years before it took root in this environment. That's why Budapest is very central to the story, while Klausenburg hasn't had Hungarians for more than a hundred years."

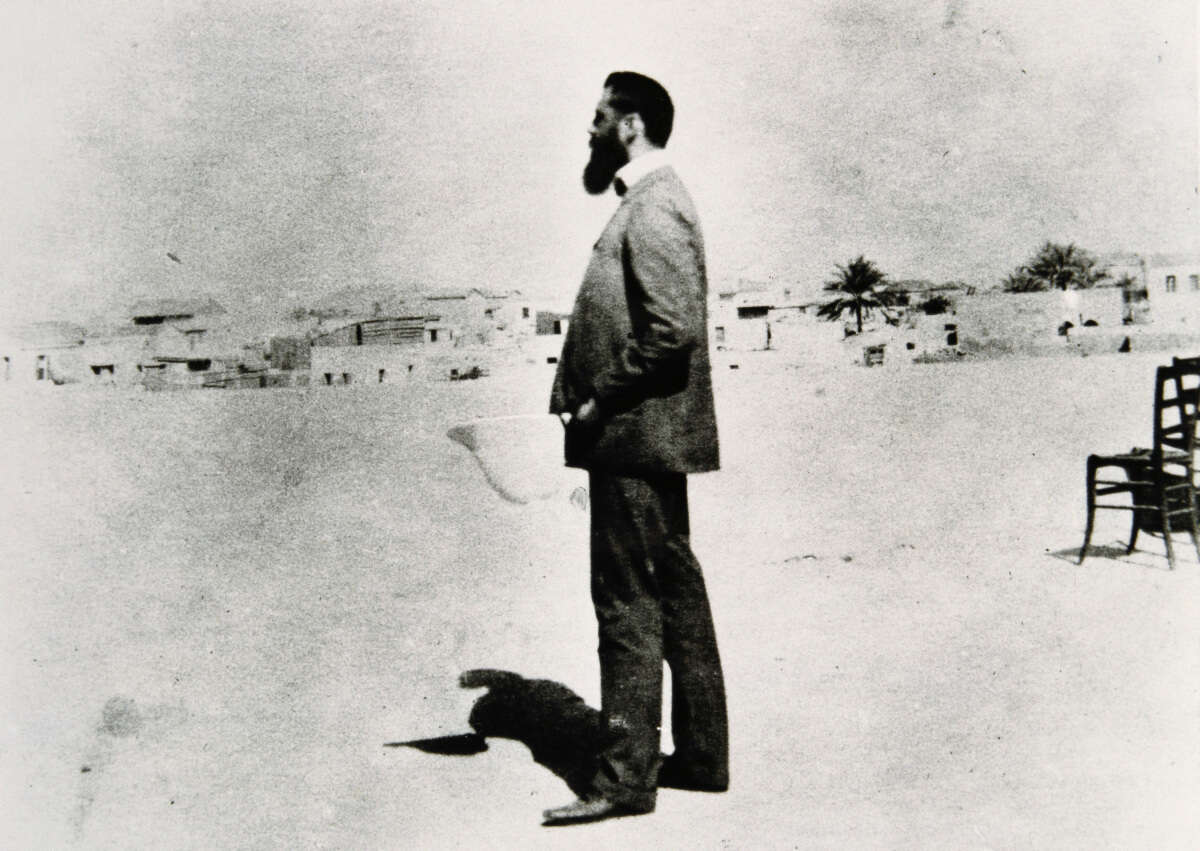

"If you want to grasp the reality of Jewish life, the paradise they had; if you want to understand why Theodor Herzl, a Hungarian Jew, had to find another place to talk about Zionism, knowing that no one in Hungary would listen to him – in Budapest you can see it before your eyes. Beyond that, there's something exceptional about this city. It was built to be an empire's capital in the late 19th century, then went through two world wars and decades of communism, yet if you have the right ears and eyes, you hear and see things. It's like walking through a living museum."

"In Budapest, the Jewish communities also separated. Today we don't see the rift with our eyes, because there are no active Neolog and Orthodox communities here anymore, but you can walk down the main Jewish street and tell how all the Jewish shops were open on Shabbat, and the city's rabbi didn't care because they weren't from his community."

And what about the Holocaust of Hungarian Jews? Almost defiantly, it's not present in your tour.

"Obviously we can't ignore the Holocaust, but there was so much in the period before it. Indeed, precisely because of Hungarian Jews' 'paradise' feeling, what happened here in the Holocaust appears as betrayal. Unlike Poles or Ukrainians, who always appeared to Jews as enemies lying in wait, in Hungary, it wasn't like that at all. The feeling of betrayal is strong and justified, but Israelis – including Hungarian natives – love Budapest very much."

"People are amazed to see that this city symbolized the height of progress in the early 20th century. The subway that ran here was the first in Europe and third in the world, after London and New York. The largest Gothic building in the world is the Hungarian Parliament. There's an interesting duality here – on one hand, it's amusing to see thousands of monuments to national heroes who never won any war. After all, this is a culture that was crushed under German and Russian boots, and never rose to be an economic power, at most it had some sports achievements.

"On the other hand, they survived. Budapest continued to be a large and prosperous city despite everything it went through, and the Hungarian language, which is different from everything around it and seemingly should have disappeared – here quite a few people are chattering in it. Maybe demographically it will end in another hundred years, because it's a small nation that can't reproduce enough, but the Hungarians managed to create culture, science, and poetry in their language. During the golden age of relations with the Jews, you could see a kind of similarity between the peoples, a population of Asian origin scattered among Europeans, an unconscious correlation of shared destiny."

I can't help but ask you about your son Dvir z"l, who was murdered in a terrorist attack in August 2019. Is Budapest for you also a place to escape to?

"I don't feel like I'm escaping from anything. Sometimes I feel a bit uncomfortable immersing myself in other things and not in memorials, although I said from day one that I don't want to fall into a place that perhaps keeps other bereaved parents alive, meaning constantly dealing with memorializing the child who died. Certainly not when I have other living children."

"Dvir was killed when I was completing my doctorate," he adds. "A year passed from then until I finished and submitted the work. After submission, I entered a mental crisis. The shiva days are also a farewell party where you discover what kind of child you raised at home, there are things that sweeten the pain and you don't really understand that he won't be here anymore. Working on the doctorate gave me more time. After I finished came the crisis, and it took me two years to get out of it."

It's not clear if this is one of the tour's goals, but a few days in Budapest with Sorek instills Hungarian pride in anyone with roots in this region – I, the humble one, am among them. A few days after returning home, the dedicated WhatsApp group is still buzzing. Pictures, documents, impressions, and summaries continue to appear one after another. I admit I'm not the type for organized tours and tours where they take me like an obedient sheep from here to there, but this time it was something different. Full of passion and love for Budapest, its Jews, its past, and its present, which is also full of Jews and Hebrew – just ask Franz Liszt International Airport.