As images emerged this week of Syrian prisoners being freed from Assad's notorious prisons, Syrian Jews who escaped to Israel decades ago were reminded of their own traumatic experiences under the regime. While welcoming its collapse, they say the documented atrocities barely scratch the surface of the systematic persecution they endured.

Even today, S. hesitates to tell everything. He's even afraid to identify himself. Years of terror under Assad's regime left deep psychological scars and persistent anxiety. His body also bears physical marks from the torture he endured while imprisoned in Syria. This week, Syrian Jewish emigrants in Israel welcomed the regime's fall, but their harsh memories from decades of tyranny under the Assad dynasty – both father and son – remain vivid.

"Life in Damascus was like living in a ghetto," S. recalls. "You couldn't leave the neighborhood without permission. For any purpose, you had to go to the Mukhabarat (intelligence) headquarters in the neighborhood and get approval. Assad Senior, may he rot in hell, made our lives miserable. Leaving the country was forbidden, especially for Jews. Anyone who spoke against the government was thrown in prison for decades, with no one knowing their fate. There was an atmosphere of constant fear."

Born in Damascus in 1947, he left at age 40. "I made aliyah through an unconventional route. We crossed the Syria-Turkey border on foot – 27 hours of walking without food or water, my family and another family, 17 people in total."

Did you believe you would live to see this regime fall?

"Honestly, no. After decades, you stop believing it could end like this."

The era that ended this week began in 1966 when Hafez al-Assad became defense minister in the Baath government. In 1971, he appointed himself president. After his death in 2000, his son Bashar inherited the position. This week, he fled with his family to Moscow as rebels advanced.

S. watched all the disturbing videos this week showing prisoners being freed from Syrian jails. "I know those places well – I'm a Prisoner of Zion. I spent a year and three months in Mezzeh prison."

At 22, married with a daughter, S. first attempted to cross the border into Lebanon. Near the border, the family was caught. "Jewish ID cards had 'Musawi' (follower of Moses) written in large red letters, impossible to miss. When we were caught, they told me to get out of the car. They took my wife and daughter out, removed the Muslim driver, and beat him severely. Blood was flowing everywhere. They released my wife and child but took me to prison. I have marks all over my body from that time – on my fingers, hands, feet, back. When I remember that period, everything goes dark," he says quietly.

When I apologize for perhaps stirring unwanted memories, he says the scars don't let him forget anyway. "I'm reminded of that time whenever I shower. Such torture in that prison, such torture. May their names and memory be erased."

Even with the slim possibility that it might now be possible, he has no interest in visiting where he grew up. "I can't look at Damascus – as far as I'm concerned, let all of Syria burn. I suffered there. I always told myself I didn't want my children to suffer like I did. When we left, we abandoned everything–- decades of work. I left my shop, my home. Within the Jewish community, we had it good, but with the regime? No, no, and no. I hope this regime disappears completely, but it still has roots there – this isn't over yet."

The peak of persecution against Jews in Syria under Assad came during wars with Israel. Arabs who fled Israel after the establishment of the Jewish state became particularly hostile neighbors. When the Six-Day War broke out, S. was visiting his fiancée's house. "We heard planes bombing; my brother-in-law and I went to look. We climbed onto the roof and watched the sky. The Palestinian neighbor went to neighborhood intelligence and reported us. Three or four armed intelligence officers came. We came down from the roof, and suddenly, they were pounding on the door, an iron door. They knocked the entire door down out of sheer hatred for us. The neighbor pointed us out. They took us, removed our belts from our pants, tied our hands behind our backs, and marched us through the streets – us and others they gathered from the neighborhood, 10 or 12 Jews. As we walked, all the Palestinian neighbors spat at us, cursed us, and then we faced interrogations at intelligence headquarters." The suspicion spread by neighbors was collaboration with Israeli fighters or paratroopers.

"In '73, when the war began, we were in synagogue," S. continues. "When they heard there was war with Israel, people left the synagogue and went home, afraid. You always knew regime officials could come whenever they wanted and do whatever they wanted to you."

He sighs deeply, hesitating whether to share another story. "I worked various jobs there. I was also in the burial society. Once, they came from intelligence on Friday night, saying, 'Come with us.' Where? 'To the cemetery.' What's at the cemetery on Friday night? 'We'll tell you later.' They took me from the synagogue on Friday night by car. We arrived there; they brought four coffins. And those coffins, I don't want to tell. Things have been hidden for almost 40 years. Secrets of 40 years. Still hard to tell."

What S. witnessed firsthand was the tragic story of four Jewish girls who were caught in March 1974 trying to escape Syria, were severely tortured, murdered, and their bodies mutilated. The event deeply shook the Jewish community.

A two-and-a-half-year-old prisoner

In his book "Escape from Damascus," attorney and CPA Jack Blanga describes the history of Syria's Jewish community and his family's escape across the border to Israel. Born in 1968, he arrived in Israel in 1980. He and his parents, Azur and Rachel Blanga, had a previous escape attempt that ended in capture and imprisonment. The father was imprisoned separately and endured hardships, while the mother was held with her son. In Israel, Blanga received a Prisoner of Zion certificate for the period he was detained with his mother when he was just two and a half years old. The detention conditions for the toddler, imprisoned with a group of women, were harsh. Water and food were barely provided, and hygiene was impossible. His release after several weeks came following intervention by international human rights organizations, who protested the imprisonment of a toddler.

Blanga is disappointed that the dictator managed to escape: "It's unfortunate they couldn't get their hands on Assad this week. After the atrocities he committed against his own people, he deserves punishment." In his book, he describes how, as a child,d he watched his father being forced to vote in Syria's unfree presidential elections, with an intelligence officer making it crystal clear to his father that there was no avoiding entering the polling station, nor avoiding marking "yes" on the ballot to support Assad's continued rule.

The horrific images from Syrian prisons distributed this week are just the tip of the iceberg, he says. "What they showed is very little. Many people simply disappeared over the years. They dissolved them, with all that implies. For us as Jews who grew up there, and also for the State of Israel, the regime's fall is definitely good news."

In 1992, following American pressure, Syria allowed thousands of remaining Jews to leave. "Syria needed US aid then, and as part of the pressure applied, they allowed Jews to leave. Their property had to be left behind. Very few have remained in Syria since then. In the early period in Israel, we had few means, and integration wasn't easy," says Blanga, who later became vice president of the Institute of Certified Public Accountants in Israel.

As an active community member here, do you have connections with the Jews who remained?

"A little, through social media. In recent days I've written to them but haven't received responses yet. These are elderly people, and it's hard to know if they're afraid or under pressure and, therefore, are not answering or if there's another reason. I hope everything is alright with them."

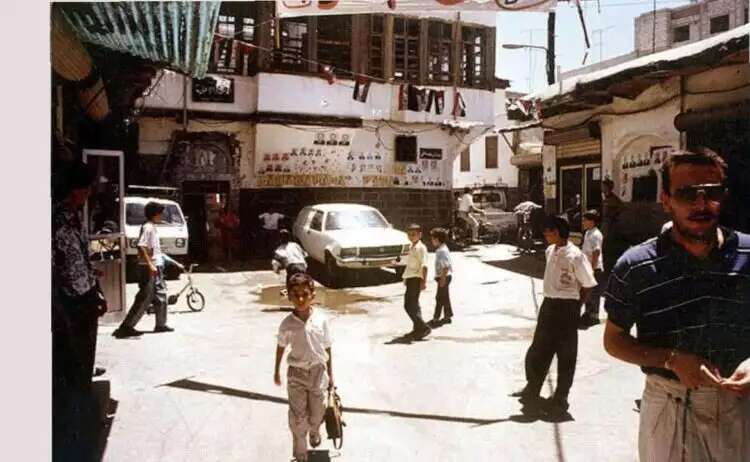

He, too, has only bad memories from his birthplace. "It's not easy growing up in a place you're forbidden to leave. We were prisoners there. You couldn't walk with a kippah in the street because they would throw stones at you. From the house where I lived in Harat al-Yahud, the Jewish Quarter in Damascus's Old City, we could see the Syrian Mount Hermon. It made me happy this week to know that our soldiers are now sitting there looking down at Damascus from above."

Following the Madrid Conference

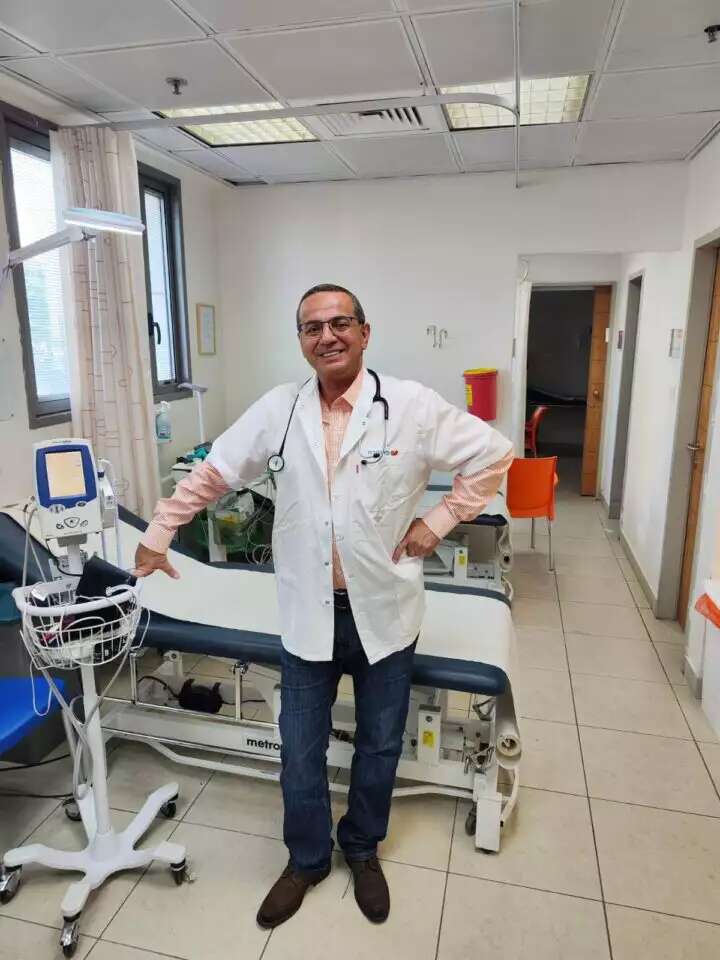

Dr. Nathan Haswa, a family physician, was born in '69. "I was born in Damascus to my parents, Haim and Frida. The Jewish neighborhood then had about 4,000 people and 23 synagogues. The Jews were essentially hostages from '48 until '92. Even before Assad's regime, they were prevented from leaving the country, and under his rule, the situation worsened. Initially, Jews were prevented from buying homes and studying at university. After several years, these prohibitions were eased, partly due to pressure from Henry Kissinger. Jews were allowed to study and hold property. In '79, there was a possibility for the temporary exit of one family member in exchange for leaving a sum of money at the Mukhabarat offices."

For many families, the general desire to escape the harsh life in Syria was intertwined with decades-long forced separation from family members. In 1942, the Jewish Agency managed to smuggle about 1,100 children from Syria to Israel, but when the state was established, the border closed, and their families remained in Syria. Thus, they were separated for decades. "Every Jew in Damascus or Aleppo waited for an opportunity to leave. There were quite a few escape attempts through Lebanon and Turkey. Some were caught at the border," Haswa recounts.

He remembers the shock that gripped the community after the horrific murder of the four girls in '74. "I was a child, but I remember we went on a kind of protest march toward government institutions in Damascus. The young girls wanted to leave the country also because they had no Jewish suitors. At one point, Kissinger asked Assad to allow 100 girls from Damascus to leave for New York. He only gave him 13."

Haswa studied medicine in Syria at Damascus University, graduating in 1991. He describes the international circumstances of the early nineties that led to change: "After the US fought Iraq and the Soviet Union collapsed, the Madrid Conference was held, and within its framework,k Israel requested that Jews be allowed to leave. President Bush Sr. asked to permit Jews to leave Syria and also to release five Jews who were imprisoned in Damascus for wanting to escape the country. They were in very bad condition. At that stage, President Assad was supposed to be 'elected' for the fourth time. Damascus Jews were asked to participate in a pro-Assad campaign in exchange for releasing three or four prisoners. I remember the propaganda signs that Damascus Jews were forced to write, including my brother Marco, saying Assad was our father, that he was a good leader."

"In '92, Jews were allowed to leave, on condition they wouldn't emigrate to Israel. A declaration was made in the Syrian parliament, where Assad said Syrian Jews were free and had full rights to leave, buy, and acquire. I remember my late father paying the government representative 250,000 liras and giving him expensive gifts – carpets and vases – to get a passport. The next stage was going to the US Embassy in Damascus. They gave visas immediately. We flew on an Air France night flight to the US, and when we landed, we were greeted by Syrian Jewish organizations and refugee organizations. I was 24. Many Jews had relatives in the US, and the celebrations at New York's airport were huge. The synagogues left behind were looted, and the houses were looted. In '94, Rabbi Albert (Abraham) Hamra, the Chief Rabbi of Syrian and Lebanese Jews, made aliyah, and Shimon Peres received him. In Syria, 300 or 400 people remained. They wrote then that the era of Damascus Jews' exile had ended."

Haswa watched images of the regime's collapse this week, but no sense of nostalgia arose in him. "The Jews who left Damascus never felt and do not feel that Syria is their homeland or that they belong to the Syrian people. Even if there's longing for school or the Jewish neighborhood, and even if, over the years, some American passport holders went to visit, the general feeling is that no one wants to remember this country. What is there to see? The neighborhood is destroyed, and the synagogues were looted. Also, those who seized power now are not peace-loving people. It's a divided and torn country. I don't foresee a particularly bright future for it. I saw atrocities on television; now they're hanging Assad regime people, acting like ISIS. There's no security there, no government. Thank God we're not there anymore."