1.

We seldom, if ever, discuss the enormous American Christian support for Donald Trump, driven by Zionist motives. That's a mistake. In political science and international relations departments, as well as in the Foreign Ministry, relationships with other nations are examined almost exclusively through the lens of economic, security, and political interests. Westerners are taught to think rationally and to regard religious beliefs as either relics of the past or private matters unrelated to state affairs. Similar attitudes exist regarding myths, the founding narratives of nations. Cultural dimensions are relegated to the background in the analysis of considerations that determine policy decisions.

This is not so when analyzing individual personalities. In personal psychology, we account for the subconscious aspects of a person's character, their dreams and desires, relationships with parents, past traumas, and other hidden elements of personality that can be more significant than openly visible traits. So why do we ignore these factors when engaging with other nations? Think of Israel: can one truly understand the State of Israel without considering the core element of Jewish faith, without acknowledging our cultural calling card – the towering textual "skyscraper" we've constructed over thousands of years? Or without recognizing the long history we carry, filled with all the traumas and hopes that inform our collective consciousness?

When I assumed my role as ambassador to Italy, I filled an entire wall in my office with foundational Jewish texts: a Bible with commentaries, the six orders of the Mishnah, the Talmud, Midrashim, the Zohar, Jewish philosophy, ethical works, and halachic responsa – this alongside contemporary Hebrew literature, poetry, prose, and scholarly works. I would introduce these books to my interlocutors – politicians, diplomats, and intellectuals – and explain their contribution to modern-day Israel. The fact that we speak an ancient language and can understand texts thousands of years old is not merely a folkloric curiosity; it sheds light on how we have walked through the "valley of the shadow of death" of history, both in the past and today. I would tell them that, to understand Israel, they must consider – among other things – the incredible historical and cultural heritage that underpins our identity as a society and a nation.

I adopted the same approach in seeking my understanding of my host nation, Italy, delving into its foundational texts, especially Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy, published in the early 14th century and marking the start of a centuries-long journey toward an Italian national consciousness. I studied Italy's unique history, which continues to influence its internal politics and foreign policy. In a broader context, although Europe is largely secular, Christianity remains part of the infrastructure of Western life, not necessarily as a religion but as a culture. The crucifixion is a profound trauma within the European collective unconscious, as is the place of the Jewish people and the Bible. A statesman who approaches the West focusing solely on material interests, without factoring in the cultural elements within the Western collective identity, may draw erroneous conclusions and misunderstand their interlocutors' intentions.

In the US, Christianity plays an even more central role, shaping American society to a far greater extent than in Europe. We must understand this in order to manage our political, military, and diplomatic relations with the US effectively. Material interests, including economic and security interests, are essential, but so too are shared values, faith, and, of course, the foundational narratives that we both share.

3.

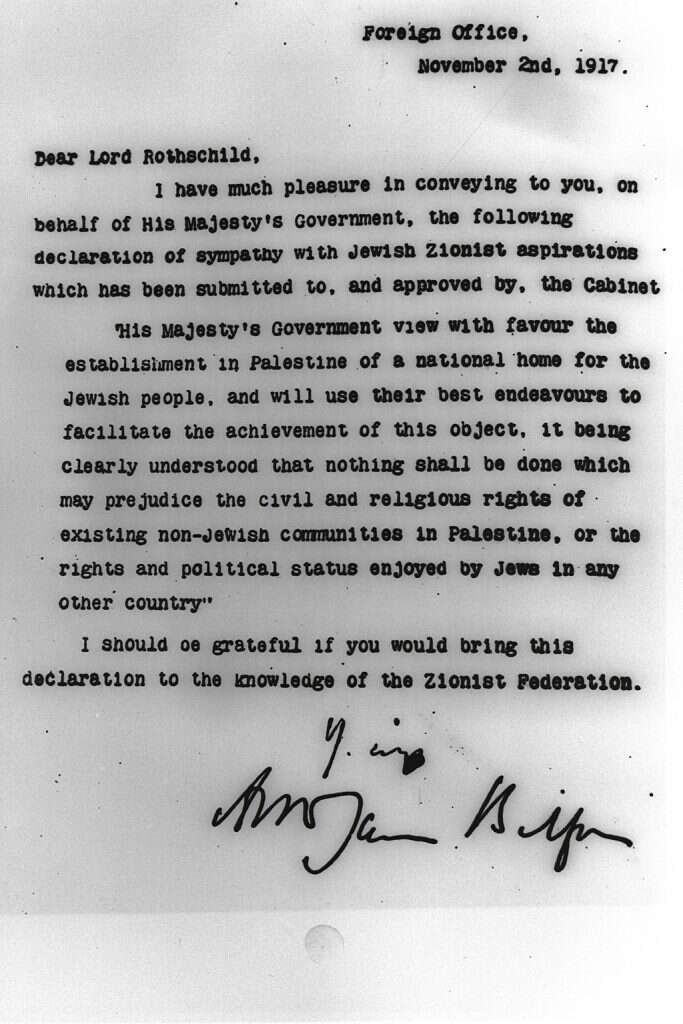

Last weekend we marked 107 years since the Balfour Declaration (November 2, 1917), which called for a national home for the Jewish people in the Land of Israel. When examining the reasons behind the Declaration, many emphasize that Britain sought a friendly presence near the Suez Canal – the gateway to India, then under British rule – and hoped for Jewish support in the US and Russia (with the hope that Jews would encourage the US to enter World War I and prevent Russia from pulling out of the Allied coalition). Another often discussed factor is the significant contribution made Dr. Chaim Weizmann, head of the Zionist movement and a scientist, to the war effort with his work in the field of munitions, which gave him influence to lobby the British and helped secure the Declaration.

However, Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour, a member of the Church of England, and Prime Minister Lloyd George, a Baptist, were also motivated by religious considerations. From childhood, they had been raised on biblical stories, interpreting them literally, unlike the Catholic reading, which saw the Church as the new "Chosen People" following the Jewish rejection of Jesus as the Messiah. Puritanism in the 17th century and Evangelicalism in the 19th century ingrained in British Christian culture a belief in the Jews' return to Zion. Balfour wrote that without the idea of a Jewish homeland, England would never have conceived the idea of a protectorate – or mandate – in Palestine."

Lloyd George acknowledged the strategic and interest-based motivations behind the Balfour Declaration but admitted that the Declaration was also inspired by the fact that "we studied Hebrew history more than that of our own country. I can name all the kings of Israel, but doubt I could remember the names of half a dozen English kings." He recounted how in his meetings with Weizmann, when the Zionist leader spoke of the Land of Israel, he would mention place names "more familiar to me than those of the Western Front."

4.

Balfour's biographer, Blanche Dugdale, who was also his niece, writes that his mother taught him the Hebrew Bible, and he maintained a lifelong interest in Jews and their history. As he grew older, his intellectual admiration and sympathy for aspects of Jewish philosophy and culture deepened. He saw the Jewish problem as being of immense importance. Dugdale recalls that as a child, she absorbed from Balfour the idea that Christian religion and Christian culture owe an "incalculable debt to Judaism," and to their shame, they have repaid it with ingratitude. Every Sunday, Balfour read a chapter from the Bible to his family; he favored the Hebrew prophets, especially Isaiah.

In the face of calls in the British Parliament to reject the mandate, Balfour defended the Declaration. He stated that while it had material benefits, "we have never pretended – certainly I have never pretended – that it was purely from these materialistic considerations that the Declaration of November 1917 originally sprang." He called for a message to be sent to every land "where the Jewish faith has scattered." Christendom, he said, "is not oblivious of their faith, is not unmindful of the service they have rendered to the great religions of the world… and that we desire to the best of our ability to give them that opportunity of developing in peace and quietness under British rule, those great gifts which hitherto they have been compelled to bring to fruition in countries that know not their language and belong not to their race… that is the ground which chiefly moves me."

5.

It was not only the British who were inspired by religious motivations; so too was the American President, Woodrow Wilson. The Zionist movement (and Balfour himself) sought Wilson's support for the Balfour Declaration, as the British depended on American support in the war. They enlisted Justice Louis Brandeis, who was close to Wilson. Brandeis did not argue politically or electorally but instead appealed to the President's Christian faith. A petition signed by leaders from various Christian denominations was presented, advocating for a Jewish state in Palestine. Indeed, about a month before the Balfour Declaration, the president allowed Brandeis to convey his "full sympathy" to Lord Balfour and the British Cabinet regarding the proposal for a Jewish homeland. Later, Wilson was thrilled by the historical opportunity that had come before him, saying that as the son of a Presbyterian minister, it was "a privilege to restore the Holy Land to its rightful owners."