Meeting former October 7 captives evokes a profound sense of respect. There's an unspoken code about what to ask and not to ask. You want to hug them, surround them with care, while also respecting their privacy. You embrace them from every angle because there's no right way to relate to someone who was in a safe room one moment, and in a basement with terrorists the next.

Photo by: Efrat Eshel

Some prefer not to talk, keeping their experiences to themselves, their families, or in closed notebooks. Others have made telling their stories their life's mission. Hen Goldstein Almog, who was kidnapped with three of her children from Kibbutz Kfar Aza and released in November after 51 days of horror, is one of them.

"I'm kind of working on telling our story," she says confidently to the camera. Her hair is tightly pulled back in a ponytail, her posture is straight and composed, as if trying to gather the broken pieces inside. "I understand that telling our story is part of the journey, and it also helps me process things. We went through so much in a short period of time, and I need to look at it several times a week to grasp it and digest it. It's exhausting, telling our story, but it's very important to me."

Walking a Timeline

"And today, today we are okay," she takes a deep breath when asked the simple question, "How are you?" "We are working on living. The grief and pain are always with us. They are ours to carry. And we have to work hard to live well. But it's important for me to build our lives as a family - a missing family, but a family that lives and hopes to live the best life we can. It's also very important to me to commemorate Yam and Nadav. We will not let October 7 define us."

Photo: From the family album

Does time passing make a difference? I ask carefully, and Hen answers firmly: "Absolutely. I walk along a kind of timeline - on one hand, not long ago, we were a whole, strong family together. On the other hand, a lot of time has passed. The one-year mark is approaching, and we are still in pain, still in the midst of the event. We are still trying to cope with what we went through and the fact that we have living and dead captives to bring back. You're constantly in this whirlpool - one step forward, two steps back."

Hen and Nadav's love story, set to mark her 50th birthday this month, began in high school. Nadav was a well-known triathlete and VP of business development at Kfar Aza's "Kfarit Industries." Over the years, they built their home in the kibbutz, where they raised their four children: Yam, 20, who was brutally murdered; Agam, 18; Gal, 12; and Tal, 9. In August 2019, they moved into a new house in the kibbutz, where they created countless cherished memories - until October 7.

Photo by: Efrat Eshel

Early that morning, when terrorists overran the kibbutz near the border, Hen and her family locked themselves in the safe room. "A deathly fear," Hen described the feelings of that horrific Saturday in previous interviews, including in this newspaper. It was a terror from the gunmen who murdered Nadav and Yam, kidnapped Hen and her three surviving children with threats and screams. A fear of death.

For 51 days, Hen and her children were held by Hamas. They were freed on the third day of the hostage exchange deal in November. Now, the four of them are starting new lives. When Hen talks about Yam and Nadav, she allows herself to give in to tears. They are everywhere - inside and out. Their smiling faces greet visitors at the entrance to the temporary house where they now live. It's a different home but feels comforting. Hen keeps the location private, unable to shake the fear of the killers' promise that they will return in the thousands next time.

Photo by: IDF Spokesperson's Unit

"I still live with the absence of Nadav and Yam, and the loss of our home. I found myself saying that 'longing' is too gentle a word because you can fondly look back on longing, but I'm still in the stage where Nadav and Yam were taken from me in a horrific way. And I need to deal with that absence, that nothingness, that loss. Now, for example, we need to decide whether to return to the south. These are decisions I always made with Nadav. Now I trust the kids, and we will make the right decision together."

Silence: The Word Hanging in the Air

"Nadav was the love of my life, my anchor. For 34 years, I admired him. He even wrote it down - he wrote a book in the past year where he said I was the love of his life, and sport was the mistress we never talked about. It was part of his essence - his dedication to sports and his work. He was self-taught and volunteered as a lecturer at Tel Aviv University, mentoring students who came to 'Kfarit.' He was a father in every sense of the word. He mastered the art of being present, even with the limited time he had at home."

Photo by: AP

She brushes her fingers across a photo of Yam on her phone. "Yam made me a mother," she says softly. "It was the happiest time of my life - becoming a mother. She was an amazing baby, spoke very early, understanding and active and joyful. She grew into an energetic child, full of confidence, then a teenager, and at 20, a woman. I felt that Nadav and I were managing the family and the children like a project together. And that fulfilled me."

"She was a lively child. Every Sunday when she went to the army, she would ask where we were eating on Friday. She was also very organized and planned her weekends, dividing them between home and her time with Tomer, her boyfriend."

What would she say now?

"Wow." She pauses. "If she were here and Nadav wasn't? We would grieve together that Nadav wasn't here. Nadav was seriously injured in a bike accident a few months before October 7, and she took care of him in an inspiring way. She took leave from the army to care for him, and we were gifted with her presence during that time."

"It feels good to talk about her," she wipes away her tears. "And she is so missed. Yam was so dominant, noisy. She left behind so much silence."

Silence. The word lingers in the air. A word repeated in many stories of mothers kidnapped or held captive with their children. A word that brings Hen back to the darkest days.

Photo: Courtesy of the family

"In Gaza, there was a lot of silencing, especially of the children. People keep asking if we were exploited or abused. No, they didn't beat or sexually assault us. But they mostly silenced the children. And they're kids - they're naturally noisy, playful, talkative, and quarrelsome. There was a young man who would silence them a lot. And I would tell him, 'Is this your only way to communicate with the children? Just to tell them to be quiet?' It was infuriating."

"It was hard. I remember that during the first days in Gaza, I forced myself not to forget the sight of Yam, bullet-riddled. It was so horrific - I saw her for just seconds before I turned to the children. I ran. In my mind, I understood that people were dying in the house, and I was going outside, to the living. It was a terrible sight. And I remember forcing myself not to forget that image."

"It was a kind of self-flagellation - 'You will not forget this, and you will deal with it and be strong.' Fortunately, it fades with time, and I remember her now as beautiful, happy, laughing, and full of life."

Talking, hurting, remembering the absence – and sometimes laughing

Hen is a social worker by training, but focused on motherhood in recent years. She "stole" moments to talk with her children during lunch or bath times, waited for her daughters to come back from outings. When we step outside for photos, we meet Gal, smiling shyly while walking with one of his guides - the boy who witnessed the worst is still able to smile.

"The kids saw their father shot and passed by him, or in some way circled around him. It's tough, but they're very strong children, and their basic trust hasn't been shattered. They give of themselves and open up. They're supported by a multidisciplinary team at school, with psychologists and guides, and I'm very grateful for that. It's crucial for our ability to cope with all these challenges. I also lean on people. I'm surrounded by a team that not only provides therapeutic support but also advises me. I'm learning to listen and decide. I fill my day with sports and make sure my day is full. And if it isn't, I work to make it full."

Photo by: Gideon Markowitz

Hen and Agam, who recently started a pre-army program, talk constantly about what they've been through. They hurt together. They remind each other of the absence. And sometimes they laugh. "There's nothing we can do, it's part of our battle - to be happy sometimes. The boys don't talk to me much, but I hear from others around us that they do open up to them. For example, Gal, who just started middle school, remembered how I told him about Yam's transition to middle school, and he smiled while talking about it."

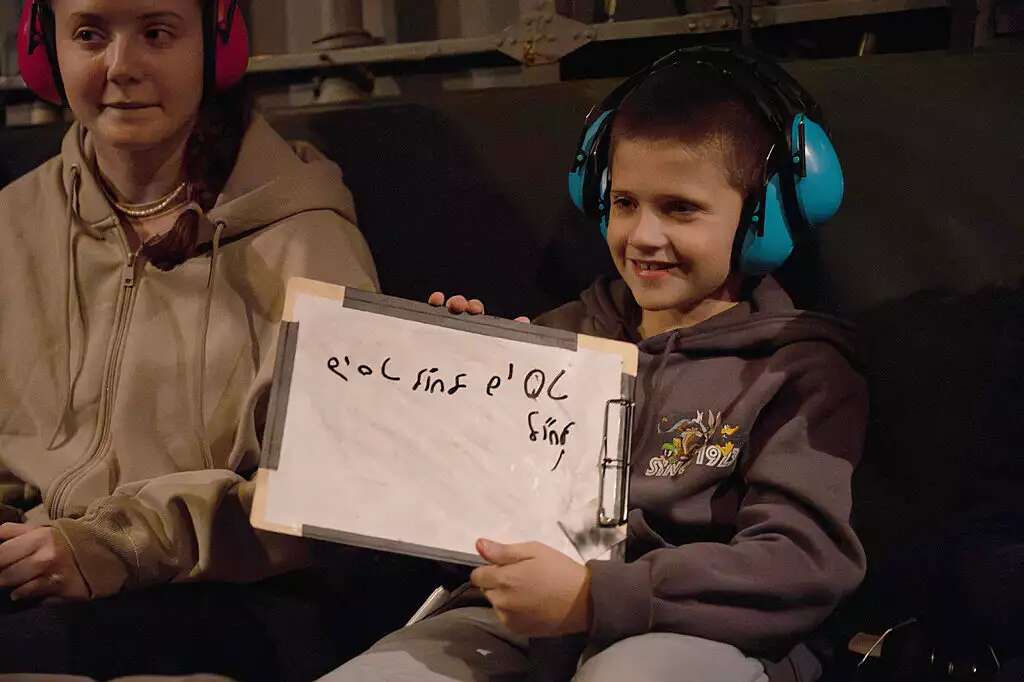

"And there are things they remember from captivity. Tal remembers that during one of the transfers, they didn't let him take a stuffed animal he had found in one of the apartments. He started crying, and a young man shoved the toy into a bag, with its head sticking out. Tal walked half of Gaza with the head of that pink, unpleasant toy poking out. He remembers that they brought a lighter to burn things they had drawn or written. They weren't allowed to write in Hebrew, only in English, or to draw. In one of the houses we stayed in for five weeks, Tal drew pictures of fighting and war. He and Gal tried to sneak the drawings into their pockets, but they were taken out. These are the things they remember. And I constantly thank God that we are here. That we made it out of that hell. We survived October 7. We survived captivity. And we are alive."

"And it was such a terrible thought. If I can say something to the hostages still there, it's important for them to know that their families are fighting like lions for them. They're not losing hope. We will not be able to recover from this event if we don't bring them back."