Around 3:00 a.m. on October 7, the Southern Command chief, Major General Yaron Finkelman, received a reassuring message: the Nukhba forces have not disappeared.

A short while earlier, on the evening of October 6, somewhere in Ashkelon, in the Shin Bet's southern command, agents noticed that dozens of SIM cards affiliated with Israeli cellular communications companies had simultaneously been activated across the Gaza Strip. These SIM cards were mostly linked to Hamas's elite Nukhba commando force.

A stunning intelligence operation conducted by the Shin Bet had made the tracking of the SIM cards possible. In many ways it was reminiscent of the methods employed in the recent pager operation against Hezbollah. Hamas had no idea that the activation of specific SIM cards in Gaza was seen by Israeli intelligence as a preliminary sign of a limited raid inside Israel. No one in Israeli intelligence had imagined a raid involving thousands of militants.

In hindsight, the information about the SIM card activations seems startling. Yet, at that moment, it was inconclusive, mainly because it wasn't the first time the Nukhba had activated their Israeli SIM cards. Although this time a far larger number of cards were activated across a wider area, past SIM card activations had only turned out to be training exercises. This was the working assumption in the early hours of October 7.

Still, both the Shin Bet and Southern Command were on high alert during those hours. Like most of the command's senior staff, its intelligence officer, Colonel A., was at home at the time. A. had risen through the ranks in the IDF's Military Intelligence Research Division, specializing in Iran's nuclear program, Hezbollah, and the Quds Force. He had previously served as the head of the Palestinian arena before being appointed in late 2020 as the Southern Command's intelligence officer. In between, he had also served as head of research in the Judea and Samaria Division and as the intelligence officer of the Samaria Brigade. He was considered a skilled and promising officer but also had a reputation for being somewhat aggressive. "There is no doubt he argues his case passionately," said one acquaintance.

In the weeks leading up to October 7, A., in his 40s, had been on paternity leave following the birth of his first son. He continued to receive intelligence updates from his home near the Gaza border, which was equipped with a secure phone line, and participated in Southern Command's weekly situation assessments. When A. heard that the SIM cards in Gaza had been activated, he immediately consulted his indicators and warnings model.

An indicators and warnings model is a collection of anomalies or activities that, when appearing together, suggest the enemy's intentions. In recent years, the Southern Command and the Gaza Division, in cooperation with Military Intelligence and the Shin Bet, developed an indicators and warnings model for a Nukhba raid into Israeli territory. However, the key element of this model was not related to the SIM cards but rather to the Nukhba terrorists themselves.

As we reveal here for the first time, Israeli intelligence had closely monitored the Nukhba. The assumption was that if Hamas was preparing for an infiltration, the Nukhba would descend into "approach tunnels" – tunnels enabling them to move close to the border fence undetected by IDF spotters - which would lead to their cell phone signals disappearing. These phones were being monitored.

When Colonel A. contacted Unit 8200 and the Shin Bet, the two parties in charge of intelligence coverage of the Nukhba, he was told that their cell phones were still within range. Both Unit 8200 and the Shin Bet firmly stated that the Nukhba forces had not vanished; on the contrary, they were going about their routine activities. Southern Command's warning model did not indicate a raid or any known action. It was simply spinning into confusion. "I detect that the other side has increased alertness," Colonel A. told his commander, Major General Finkelman, in a phone call in the early hours of October 7, "but I don't understand why."

The sad truth is that during those critical hours, the lower ranks of the Nukhba followed their usual routine. In fact, at that point, even the Hamas terrorists themselves were unaware that within a few hours, they would be launching a war. The order only reached them around 4:00 a.m., during prayers at the mosques. Even then, the Nukhba did not enter the tunnels. Instead, they stormed Israel en masse, above ground, taking with them cell phones with Israeli SIM cards.

"Incredibly frustrating"

Why did Southern Command's intelligence officers miss Hamas' surprise attack? What transpired that night within the intelligence unit of the Gaza Division, which is part of the command and is tasked with physically defending the border? How could these two bodies – armed with advanced intelligence capabilities, connected to every intelligence agency in Israel, located a stone's throw from the Gaza Strip, and busy 24/7 observing and researching Hamas – fail so catastrophically? "I keep asking myself that question," says a former senior IDF officer who served as a reservist in Southern Command during the war. "I don't have an answer, and it's incredibly frustrating."

To attempt to answer this question, we have to go back 50 years. Following the intelligence failure of the Yom Kippur War, a decision was made to rebuild the IDF's intelligence directorate. The realization that the Intelligence Directorate's research division, the primary body responsible for intelligence assessment, had been deeply entrenched in a mindset that left it blind to the enemy's activities on the ground, led the system to place more emphasis on intelligence gathered from the field itself, rather than relying on strategic analyses of various kinds.

One of the key decisions in this regard was to strengthen the intelligence bodies of the regional commands and regular divisions stationed along the borders. "The principle is pretty straightforward," says a former senior IDF officer. "The responsibility of the Intelligence Directorate and its head, who is defined as the 'national assessor,' is to provide strategic intelligence to decision-makers. After Yom Kippur, the system was rebuilt in a way that granted the commands and divisions the authority and responsibility to investigate their own areas at the tactical level. When something unusual happens in the field, the people expected to disregard preconceptions and alert everyone are the command intelligence officer and the division intelligence officer, and more precisely, the head of the command and the division commander. Their job is to confront all the strategists and say, 'Friends, you're talking nonsense. We're seeing something completely different on the ground.'"

"Even if the research division says Hamas is deterred, but the officer in the Gaza Division or Southern Command see indications of preparations for an attack, they are unequivocally supposed to sound the alarm," adds Lt. Col. (res.) Avi Shalev, a former researcher on the Palestinian arena in the research division and author of the book "The only Jew in the room". According to him, "That's precisely the role of the intelligence officers in the division and the command – to question the research division's assumptions."

The decision to transfer more authority and intelligence tools to the commands and divisions was also derived from the fact that, ultimately, it is they, not the research division sitting in the Kirya in Tel Aviv, who are responsible for defending the border. "Generally, the closer you are to the field, the more alarmist you become because you're the one who will be attacked in the event of war or an incursion," says a veteran intelligence officer. "That was also my expectation from the Southern Command and the Gaza Division: not to tell me Hamas is deterred, but the opposite. That's why their failure is even greater than that of the Intelligence Directorate."

Much has been said about the responsibility of the Intelligence Directorate for the intelligence failure of October 7, and rightly so. However, the investigation by the Weekend Magazine, which includes interviews with a long list of current and former senior officers in the Southern Command, the Gaza Division, and the Intelligence Directorate, outlines the chronology of the intelligence failure within the field units – at the command and the division level – that are supposed to detect every small movement on the ground.

"The intelligence failure of the command and the division didn't begin on October 7; it started much earlier," says a source well-acquainted with the southern sector. "They should have taken a series of actions beforehand to avoid the events of that night. By the time we got there, it was already too late."

According to sources familiar with the intelligence that did flow to the command and the division on the night of October 6-7, it is true that this intelligence didn't amount to a warning. According to them, even within the Shin Bet, Unit 8200, and the research division, not a single intelligence officer suggested, even in a whisper, raising the alert due to an impending raid.

According to a source familiar with intelligence work in Southern Command, 98% of the intelligence reports that reach the command come from Unit 8200. It wasn't always this way: Colonel (res.) Roy Tamir, who served as head of intelligence in Southern Command until 2018, published an article recently in the Shiloach magazine titled "Military Intelligence: Portrait of a Failure." In the article, Tamir analyzes what he describes as Military Intelligence's dangerous addiction to technology-based intelligence in recent years, which, in his view, has been detrimental to intelligence work. "A scenario developed where the technological solutions to various issues became almost an end in itself," he explains. "Without fully realizing it, Military Intelligence evolved from being an intelligence agency that technological capabilities into a technology organization that handles intelligence."

"Stuck in the Pipeline"

In the dead of night, sometime in 2023, officers in the Gaza Division issued an important intelligence alert. According to information accumulated by the division's intelligence unit, an assessment was made that a group of terrorists was preparing to carry out an imminent attack against our forces. Following the alert, the division commander, Brigadier General Avi Rosenfeld, placed the entire sector on high alert: Forces from the Maglan and Egoz units were deployed in ambushes, attack helicopters hovered nearby, and Air Force drones were sent to patrol along the border fence. Ultimately, the attack did not materialize.

A few months later, on the night of October 6-7, Rosenfeld did not raise an alert, even when Hamas' Nukhba forces entered Division HQ at the Re'im base. "A more risk-averse division commander, one who doesn't take chances, would have mobilized his entire division much earlier without asking anyone for permission," says a former senior officer.

Rosenfeld, a former commander of the elite Shaldag Unit, is well-acquainted with Hamas. In July 2017, he was appointed commander of the Northern Gaza Brigade, completing an intense term that involved dealing with the March of Return protests and incendiary kites sent across the border to start fires. During his tenure, he received a reprimand from the Chief of Staff after "operational lacunae in the conduct of the forces" in his sector led to an anti-tank missile hitting a bus that had been sent to pick up soldiers at the Black Arrow Monument contrary to regulations as the monument faces the Gaza Strip and is exposed to direct fire.

Despite moving forward with his impressive military career, climbing the ranks to brigadier general, and setting up the 99th Division, Rosenfeld wasn't initially taken into account for the command of the Gaza Division, when the position became available in mid-2022.

According to several senior IDF officers at the time, the leading candidate to command the Gaza Division was Brigadier General Dan Goldfuss. "But Goldfuss is a maverick who says what he thinks, he's independent, and he's not an easy commander to manage," says one of them. "That's precisely why then-OC Southern Command Eliezer Toledano didn't want Goldfuss as [Gaza] division commander."

Toledano brought Rosenfeld in through the back door, and he got the job. "That's because Rosenfeld is a pleasant, agreeable commander who placates his superiors, but he also has less sharp combat instincts," says the same senior official. "In my opinion, if Goldfuss had been appointed as division commander, October 7 would not have happened."

It is impossible of course to determine what might have been. People who spoke with Rosenfeld claim that, at the time, he was confident in the division's capabilities and felt he was the right man to lead it. All this remained true until the morning of October 7. "The gap between what he felt and what actually happened is enormous," says one of them. Rosenfeld himself wrote in a resignation letter submitted to the Chief of Staff in June: "I failed in the mission to protect the Gaza Envelope."

Why didn't Rosenfeld, who was fully aware of the SIM card activations in Gaza, raise the division's alert level, as he had done with the previous warning? Perhaps because, like the command's intelligence officer A., he relied mainly on the intelligence provided by the Intelligence Directorate and the Shin Bet.

According to a source familiar with intelligence work in Southern Command, 98% of the intelligence reports that reach the command come from Unit 8200. It wasn't always this way: Colonel (res.) Roy Tamir, who served as head of intelligence in Southern Command until 2018, published an article recently in the Shiloach magazine titled "Military Intelligence: Portrait of a Failure." In the article, Tamir analyzes what he describes as Military Intelligence's dangerous addiction to technology-based intelligence in recent years, which, in his view, has been detrimental to intelligence work. "A scenario developed where the technological solutions to various issues became almost an end in itself," he explains. "Without fully realizing it, Military Intelligence evolved from being an intelligence agency that technological capabilities into a technology organization that handles intelligence."

The problem on the night of October 6-7 was that the sophisticated technological intelligence on which the command and division relied simply didn't see what was happening on the ground in Gaza. Sources familiar with the details insist that no intelligence from the various collection agencies accumulated on Finkelman's and Rosenfeld's desks during the night to indicate what was about to occur. Not even close. "Rosenfeld knows Gaza well," says a source in the division, "but on that night, there was no intelligence indicating plans for a raid, certainly not anything on such a scale."

Ongoing IDF investigations into the events have revealed that several pieces of intelligence were collected that night which could, perhaps, have changed the intelligence picture, according to person involved in the investigation. But for some reason, they weren't analyzed in time or "got stuck in the pipeline."

"It will take us a long time to understand why the system didn't work properly," says the source. "This is painstaking work."

According to sources exposed to the intelligence that did flow to the command and division on the night of October 7, it indeed didn't amount to a warning. According to them, not a single intelligence officer in the Shin Bet, Unit 8200, and the research division, made even the slightest mention of issuing an alert for an impending raid, let alone for war. "There wasn't even a debate," says one source. "There are three levels of alert in the IDF," he says, "alert, readiness, and advance warning. That night, they didn't even discuss advance warning."

In contrast, a former senior IDF officer claims that, based on the partial information held by Southern Command at the time, the entire sector should have been mobilized. "It is evident that the command and division commanders were concerned about the intelligence they had," says the former officer. "After all, they have the authority and responsibility to issue an alert, and according to regulations, they don't need anyone's approval. They are the ones who are on the ground, know the territory and are supposed to attune to the fact that that something is going on. Instead, Finkelman shifted responsibility to the Chief of Staff and called to hold a consultation with him at four in the morning."

Southern Command contests this version of events and says that in his conversation with the Chief of Staff, Finkelman didn't seek to hold a consultation but called to update him on the situation and request reinforcements in the form of helicopters and drones.

Like Rosenfeld, the Gaza Division commander, Finkelman, did not raise the alert level of the forces on the ground. Assuming that no attack was expected from Hamas in the coming hours, he ordered all his staff to arrive at the command base in Beersheba by 7:30 a.m. for a continued assessment. The command's intelligence officer, Colonel A., began making his way to Beersheba at 6:45 a.m., fifteen minutes after the surprise attack began. At that time, Finkelman himself was still on the outskirts of the city.

"Right In Front of Their Eyes"

After the Yom Kippur War, responsibility for intelligence was transferred to regional commands and divisions, alongside the reallocation of resources and personnel. Today, a regional command intelligence unit consists of approximately 250 people, and is led by an intelligence officer with the rank of colonel (as opposed to the former rank of lieutenant colonel). The command intelligence officer is appointed jointly by the head of the Intelligence Director and OC of the command, with the authorization of the Chief of Staff. This officer has senior stature with broad authority.

The command intelligence officer tasks various intelligence agencies – such as Unit 8200, the Shin Bet, the Air Force, and others – with specific assignments and directs them to gather intelligence in areas of interest. "For example, the command intelligence officer is one of the entities operating Unit 8200 in their sector of responsibility, alongside the Shin Bet and the Intelligence Directorate," explains Colonel (Res.) Ram Dor, a former intelligence officer of Central Command. "Even if Southern Command is allocated aerial visual assets, such as a drone hovering over Gaza to collect intelligence, it's the command intelligence officer who defines the mission. Divisions and even brigades can also receive intelligence allocations and operate them according to their needs."

The command's intelligence unit also includes a research body, a kind of smaller version of the Intelligence Directorate's research division, which analyzes all the collected intelligence and produces assessments. In recent years, Southern Command and the Gaza Division, like other commands and divisions, have received advanced intelligence allocations costing millions of shekels, which they operate independently.

In Southern Command's case, the transformation went even further, turning the Yarkon Intelligence Directorate base, located near Kibbutz Urim in the western Negev, into the Directorate's first multidisciplinary base. Units from various Intelligence Directorate collection branches were relocated from their original bases to Yarkon to facilitate direct transfer of data to the division's intelligence officers. "We 'injected' them with all kinds of intelligence," a former General Staff officer says. "Satellite images, signals intelligence, cyber intelligence – all just a ten-minute drive from the division." A senior reserve officer in Southern Command adds: "The intelligence officers in the south had everything. All the intelligence was right in front of their eyes."

The IDF has not yet completed its investigations into the intelligence failures of October 7, but various reports suggest that a significant amount of intelligence regarding Hamas' preparations for the raid was directed to the Gaza Division rather than Southern Command, despite the fact that the division's intelligence unit is smaller compared to that of the command and lacks substantial research capabilities."

The most striking example of this is the case of V., a non-commissioned officer, from Unit 8200, who was part of a special intelligence team assigned to the Gaza Division, tasked with investigating Hamas' training exercises. V., along with other officers from Unit 8200, argued that it seemed Hamas was seriously preparing for a large-scale, significant raid under the code name "Walls of Jericho." In an email exchange, which included Lt. Col. A., the intelligence officer of the Gaza Division, V. wrote that "the drills show that the "Walls of Jericho plan is operational and being actively rehearsed, meaning that Hamas already has forces practicing these scenarios and which are capable of carrying out the plans when the order is given."

Lt. Col. A. responded to V., dismissing her scenario as "imaginary," and stated that Hamas' exercises were mere "showmanship." V.'s warnings were lost within the established preconceptions.

The information provided by V. reached the division but did not make it to Southern Command or its intelligence officer. According to some in the command, it was merely one piece of intelligence among a vast collection of reports. "You can't treat every piece of information as absolute truth," they say.

Even when, three weeks before October 7, a detailed report titled "A detailed picture of Hamas training for a raid" was compiled by Unit 8200, it was sent to the division's intelligence unit, not to the command's intelligence unit. The report, which described a series of training exercises conducted by Hamas' elite Nukhba units to seize military outposts and kibbutzim, including rehearsals for taking hostages to the Gaza Strip, was not given serious attention.

"The power of preconceptions is that you want to believe in them," explains a veteran intelligence officer. "The nature of intelligence work in indications and warnings goes against human instinct. The challenge is to gather pieces of information and determine if they indicate a need to shift perceptions. In theory, the division is the optimal place to take intelligence from the field and use it to break down strategic intelligence perceptions. The command does not experience the field at the same resolution, and certainly not the research division. Unfortunately, the Gaza Division of October 2023 did not break free from its preconceptions."

"A Question of Conduct"

Additional intelligence that could have indicated that Hamas was preparing for a large-scale raid was sent to the Gaza Division by Unit 414 of the Border Defense Corps, which is operationally subordinate to the division. Two of the unit's companies are staffed by female lookouts stationed at the Nahal Oz observation post, controlling cameras along the entire border fence. In the months leading up to the surprise attack, these lookouts observed a series of suspicious actions by Hamas and reported them.

Amit Yerushalmi, a lookout stationed at Nahal Oz who was discharged from the IDF about a month before the war broke out, testified recently before the "Civil Commission of Inquiry" into the events of October 7. She recounted how "three times a day, a convoy of pickup trucks would drive [parallel to] the route from Netiv HaAsara to Kerem Shalom – around 30 trucks with armed terrorists carrying cameras, flying Hamas and Palestinian flags, driving 300 meters from the fence and stopping at every position... we reported everything."

Eyal Eshel, the father of lookout Roni Eshel, who fell at Nahal Oz, said: "The lookouts issued warnings, wrote reports, and entered the data into system, but no one analyzed the intelligence they collected."

A former senior officer in Southern Command intelligence said the decision on whether to use the intelligence provided by the lookouts and how to respond to it rests with the division's intelligence officer. "It's a question of conduct and organizational culture," he said. "In the end, it comes down to what each rank considers important, what they focus on, and their priorities. Is the intelligence from the lookouts part of the larger intelligence picture? Certainly. But some use it sagely, and others more superficially."

However, another source familiar with Southern Command's operations argued that the information provided by the lookouts was well-known to both the division's intelligence officer and the division commander. "You didn't need to be a lookout to see the convoys of trucks driving along the fence every day. Hamas started with one truck, then ten, and eventually 30 every morning," he said. "The division commander saw them with his own eyes. Hamas simply changed the reality on the other side of the fence, and everyone became accustomed to it."

Southern Command intelligence officials also claimed that the lookouts' reports reached them and were taken seriously in assessments, but they did not indicate any changes in Hamas' routine activities, and thus no warning bells were triggered. "The security reality in Gaza was that Hamas could do whatever it wanted on its side, as long as it stayed a certain distance from the fence," a knowledgeable source said.

"Someone Gave Up"

One possible explanation for why intelligence wasn't pieced together into a full picture could be how responsibility for intelligence collection and analysis in Gaza was divided among different intelligence bodies. This kind of division is done in every sector and adjusted over time to reflect changes on the ground. However, sources we spoke with say the way this was in Gaza was more rigid than in other sectors, creating a significant separation between agencies. "It was clear to me that something was falling between the cracks," says a source familiar with the intelligence responsibility in the area.

One possible explanation for why intelligence wasn't pieced together into a full picture could be how responsibility for intelligence collection and analysis in Gaza was divided among different intelligence bodies. This allocation of tasks is common in every sector and is periodically adjusted to reflect changes on the ground. However, according to sources we spoke with, the way it was handled in Gaza was more rigid than in other sectors, leading to significant gaps between the various intelligence bodies. "It was clear to me that something was falling through the cracks," said one source familiar with the allocation of intelligence responsibilities in the sector.

The Gaza Division was responsible for intelligence regarding Hamas' offensive systems along the border, including snipers, anti-tank units, the Nukhba forces, and from 2021, mortars. Southern Command was tasked with investigating Hamas' tunnel systems, command structures, and rocket launch systems (here as well, there was another colossal failure as the command did not detect ahead of time the massive barrage Hamas launched on the morning of the attack).

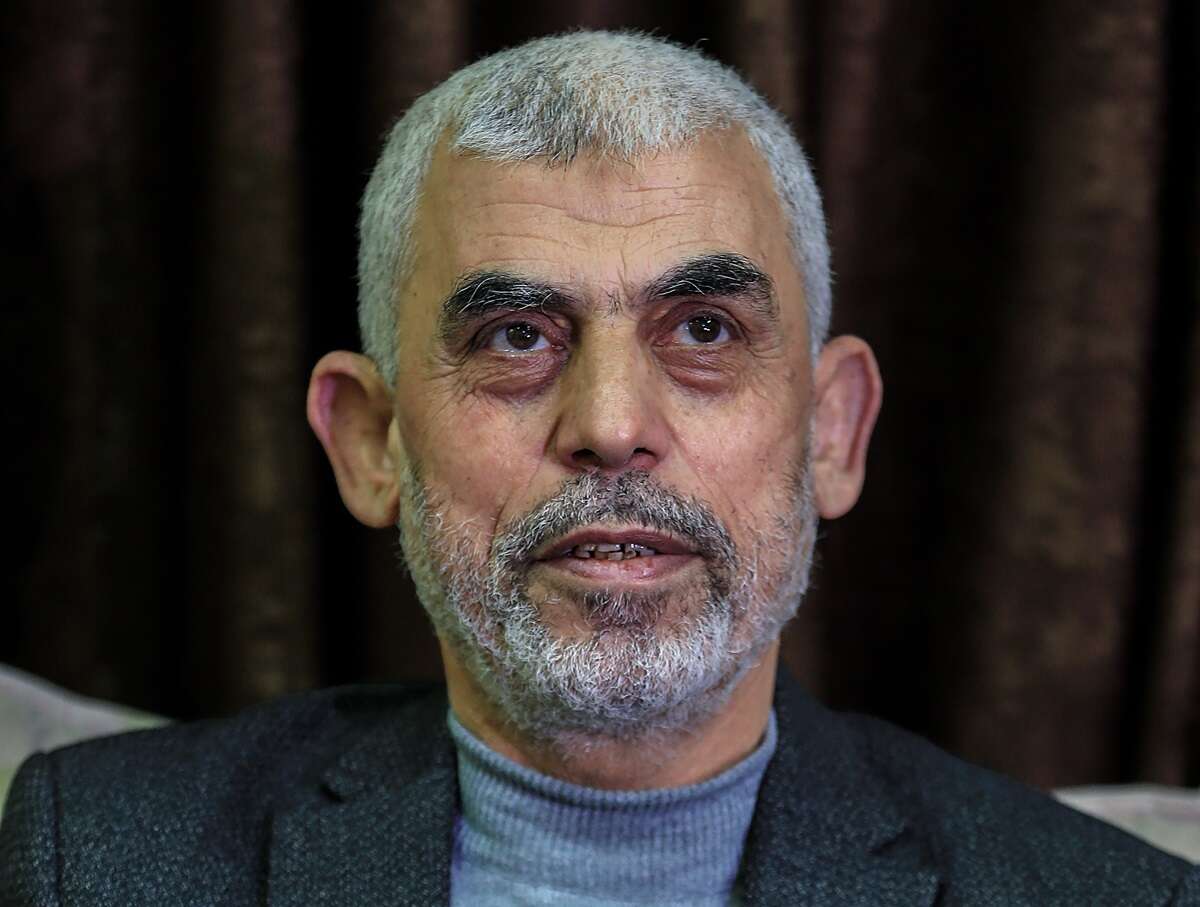

Southern Command was also responsible for researching senior Hamas military officials, such as Mohammed Deif and Marwan Issa. Meanwhile, IDF Military Intelligence focused on political leaders like Yahya Sinwar, Ismail Haniyeh, and Saleh al-Arouri, as well as what it calls Hamas' "orientation and force buildup." The Shin Bet conducted its own intelligence monitoring at all levels of the organization. "Each of us failed to identify something in our own sector," said a source at Southern Command.

The allocation of tasks wasn't only based on sectors but also on geography. The Gaza Division was responsible for intelligence coverage of the area between the final row of houses in Gaza and Israeli territory. Sources who spoke with the division's intelligence officer, Lieutenant Colonel A., when he was appointed in May 2023, recommended to him that he resign because of this responsibility.

"In Lebanon as well, the division holding the border has responsibility from the last row of houses to the fence," explains a former senior officer. "But in Lebanon, there is a depth that provides a safety buffer, whereas in Gaza the area [between the last row of houses facing Israel and the border] is much narrower. The Gaza Division intelligence officer is supposed to provide warnings of any threats to the surrounding communities. He must inform his forces if an incident is imminent, but this threat can also come from behind the last row of houses. If I don't collect intelligence on that area, how will I know to issue a warning?" A former intelligence officer in Southern Command called the situation "completely illogical."

Another source familiar with the Gaza Division argued that in recent years, the division allowed Hamas forces to approach the fence area, effectively losing control of what was once known as the "perimeter."

"After Operation Guardian of the Walls, there was a perception that Hamas was deterred, and at the same time, the double [border] fence and barrier were completed," he said. "Under the new defense concept, emphasis was placed on the area between the fences, known in the IDF as the 'Safari.' Our operations inside the perimeter beyond the fence significantly decreased. Someone gave up on defending the fence area."

Perhaps the most striking illustration of this was the deaths of Staff Sergeant Aviv Levi, who was killed by sniper fire along the fence in 2018, and Staff Sergeant Barel Hadaria Shmueli, who was shot with a pistol on the border wall in 2021. Within three years, Hamas operatives advanced several hundred meters until they reached the fence almost unhindered. Another example of the abandonment of the fence area occurred in the months leading up to October 7, when under the cover of protests along the fence, Hamas operatives attached explosives to the barrier. Only in hindsight did the Gaza Division realize that the protests were part of a deception exercise that allowed Hamas to observe IDF operations along the contact line – after declaring protests over, the IDF would lower the alert level in the sector.

Working Assumptions

Another reason why no alert was issued by the Southern Command ahead of the Hamas assault of October 7 may be linked to changes that occurred in the command's intelligence structure.

The Southern Command's intelligence unit is divided into several branches. For example, the field section is responsible for analyzing aerial photos, providing intelligence aids to forces, and studying the terrain in the sector. The targeting and strike coordination section is tasked with collecting intelligence on terrorist operatives and infrastructures and converting them into targets for strikes. However, traditionally, the most prestigious and significant branch within the Southern Command's intelligence unit has been, and remains, the counterintelligence section, which is responsible for researching the terrorist organizations themselves.

Until a few years ago, a department called "indications and warnings" operated within the counterterrorism department. The role of the officers in this department was to take all the intelligence gathered by the command and generate specific alerts for attacks. "These are people who wake up in the morning and look for enemy activity – whether its firing at the fence, throwing explosives, or attempting infiltrations," says a former senior intelligence official at Southern Command.

In 2018, during Brigadier General Amit Sa'ar's tenure as the Southern Command's intelligence officer (on October 7, Sa'ar was already head of the Research Division at Military Intelligence and has since retired for personal reasons), a formal procedure was carried out with the approval of the head of Southern Command and the head of the Intelligence Directorate, to restructure Southern Command's intelligence unit. One of the changes was renaming the indications and warnings department the "Intelligence Center," a change that was more than just semantic. Until then, the indications and warnings department at Southern Command was involved in both gathering intelligence and researching its findings, with the primary focus being on identifying deviations from routine that could indicate an intent to carry out an attack. Following the change, all intelligence gathering was transferred to the Gaza Division, and the Intelligence Center focused solely on identifying anomalies within the intelligence collected by the division.

Some in the command felt that this change was excessive, arguing that "duplication is necessary in the field of indications and warning."

A source familiar with Southern Command's intelligence unit said: "The Gaza Strip is a very dynamic arena. In the north, for example, there is an understanding that Hezbollah is a centralized organization, where decisions regarding attacks are made in an organized manner, leaving less room for local initiatives. However, various organizations operate in the Gaza arena, not all of them under central control, thus the issue of attack indications and warnings is deeply embedded.

"What wasn't as deeply embedded was the possibility of a large, bold military operation. I get the impression that in the Southern Command, there was too strong a dichotomy between routine, meaning indications and warnings for specific attacks, and war. War was generally perceived as something we would initiate rather than something that could be forced upon us by initiative taken by the other side. At the Intelligence Center, which focused mainly on providing alerts for attacks and local escalations, they probably didn't realize that a full-scale war was even possible. They didn't consider how an all-out war might break out. The assumption was that we would be the ones to decide when a war starts."

There were also other issues with the Southern Command's intelligence unit in the period leading up to October 7. Conversations with junior personnel in the system suggest that they felt the Intelligence Directorate and the General Staff had "neglected Southern Command intelligence, sending less competent people and providing less budgets. Everyone thought Hamas was deterred." According to a more senior source in the command, "There's no doubt that Gaza received less attention from an intelligence perspective, both in terms of resources and coverage capabilities. Gaza was of significantly less interest to the Intelligence Directorate. Everyone was focused on Hezbollah and Iran."

They Built a Wall Together

Another source points to a different phenomenon, which, in his opinion, had an impact on the quality of the intelligence work within the command. "Traditionally, a relatively large number of yeshiva students serve in the Southern Command's intelligence unit," he says. "There are both advantages and disadvantages to this. On the one hand, they are usually highly motivated, intelligent, and hardworking.

"On the other hand, as yeshiva students, they serve in the role for a relatively short period, and in general, in my opinion, they tend to be very conformist. I believe that yeshiva students are drawn specifically to the Southern Command because it's an open base, unlike, for example, the Northern Command. Since most of them are already married, serving in the Southern Command allows them to return home to their families almost every day."

The intelligence failure wasn't only related to structural changes in Southern Command but also to processes within the Intelligence Directorate – the body responsible for training the intelligence personnel who serve in the command and division's intelligence units and which shapes intelligence warfare doctrine. Ironically, the "injection" of extensive intelligence into the field levels in the division inundated them with technological intelligence, leading them to rely less and less on what they could see with their own eyes in the field.

"Division intelligence is based on field intelligence, but the division's intelligence officers, who grew up in the Intelligence Directorate, became addicted to SIGINT (signals intelligence, handled by Unit 8200)," says an IDF intelligence officer. "As a result, they also ignored field reports from the lookouts and others. What we see here is a combination of deep trends that characterize not only the Southern Command or the Gaza Division but the entire intelligence array. The personnel who have filled intelligence roles in the command and division in recent years embody these trends in the deepest possible manner."

This refers to our acquaintance, Colonel A., the intelligence officer of the command, and Lieutenant Colonel A., the division's intelligence officer, a graduate of the prestigious "Havatzalot" program – and the son of a senior security figure – who dismissed warnings from Sergeant V. from Unit 8200. Several people we spoke to praised the professionalism of both officers, but they also described them as particularly opinionated and resistant to accepting alternative viewpoints. "Neither of them is sufficiently skeptical," says a veteran intelligence officer.

"Together, they built a wall," says a person who worked with both officers. "This cadre was very confident, to the point of arrogance. Such individuals are dangerous in this specific role of intelligence officers because they have a tendency to silence those around them. In the business of indications and warnings, that's exactly the opposite of what you want."

Lieutenant Colonel A., the divisional intelligence officer, is expected to end his term soon, and his replacement has already been appointed. Colonel A., the command's intelligence officer, entered the office of his commander, Southern Command General Finkelman, in the first weeks after the war broke out and offered his resignation. Finkelman rejected it. Shortly after, A. was caught having an affair with a female officer under his command and left his position. He currently serves as the IDF's representative to the National Cyber Directorate.

The IDF spokesperson's office responded: "The IDF is focused on achieving the war's objectives while also continuing to advance the investigation into the events of October 7, in accordance with the situation assessment and operational efforts."