1.

As I wandered through the airport, I stumbled upon a group of Hassids forming a minyan. On a nearby shelf, a Chumash Devarim (Book of Deuteronomy) with the Or HaChaim commentary caught my eye. Rabbi Chaim ben Attar, a descendant of Spanish exiles, was born in Morocco in 1696. In the summer of 1741, he arrived to the Holy Land after he made a decision to live there, stayed in the north for a while, and eventually settled in Jerusalem, where he established a yeshiva. He passed away about a year later, in July 1743, leaving us with treasures of wisdom, mysticism, and original interpretations. In the last Sabbat of the past Hebrew year, we read: "You stand this day all of you before the Lord your God... Every man of Israel... from the hewer of your wood to the drawer of your water… to enter into the covenant of the Lord... that He may establish you this day as His people..." (Deuteronomy 29:9-12). Moments before his death, Moses forges another covenant with the people in the plains of Moab, recreating the Sinai covenant made forty years earlier. This was not just a religious covenant but a national one: "to establish you this day as His people."

And here's Or HaChaim's interpretation: "It seems that Moses' intention with this covenant was to make them responsible for one another so that each would strive for the well-being of his fellow... And this obligates each one for his Hebrew brother according to the ability of each individual." How does Rabbi ben Attar deduce that Moses' intention was a covenant of mutual responsibility? From the unusual opening: you are "standing" (nitzavim), not just "present" or the like. He rightly proves this from "the young man who stood over the reapers" in the Book of Ruth (Ruth 2:5), meaning the one in charge of them. In other words, Moses tells his flock: I am parting from you, and from now on, each of you will be in charge of everyone, "standing" means being responsible for one another, to protect and support and care, to comfort and teach, and if necessary – even to sacrifice one's life for the salvation of the people, as we see today. You are together, Moses says, in successes and failures; no one is an isolated atom; we are all responsible for each other.

2.

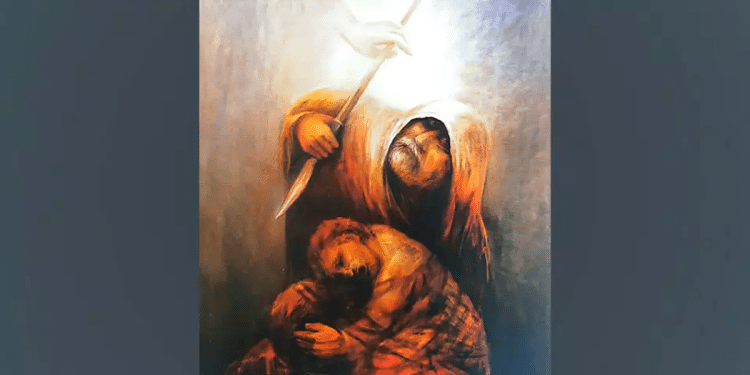

On the eve of last year's Rosh Hashanah, we prayed, "May the year and its curses come to an end, may the year and its blessings begin," and the next day we trembled as we recited "Unetanneh Tokef": "Who shall live and who shall die, who in good time, and who by an untimely death. Who by water and who by fire, who by sword and who by wild beast, who by famine and who by thirst, who by earthquake and who by plague, who by strangulation and who by stoning. Who shall be at rest and who shall be wandering, who shall be tranquil and who shall be harassed, who shall be at ease and who shall be afflicted, who shall become poor and who shall become rich, who shall be brought low, and who shall be raised high..." Chilling. Since then, we have been beside ourselves. The war in the south and north – especially the great spirit we have experienced since then among our soldiers, in the words of bereaved parents, and among the general public – is stronger and more determined than we were used to, partly due to the desire to correct what we spoiled on that Sabbath. Hence the great joy over the victories, over the eradication of evil from the world, over the destruction of our enemies and those who seek our lives. There is added value to this joy after October 7, a value of correction. We live in a complex emotional and national reality of "an eye weeps bitterly while the heart rejoices," as Rabbi Judah ibn Abbas put it in the 12th century in his poem about the binding of Isaac, "When the gates of favor are about to open." And the fate of the binder is more terrible than that of the one bound on the altar.

3.

There is only one commandment in the Torah for Rosh Hashanah regarding our days: "It shall be a day of blowing (in Hebrew: "teruah") the horn for you" (Numbers 29:1). Since the beginning of the war, the shofar has accompanied our soldiers on many occasions, especially before going into battle. It's doubtful if there's an item that's perceived as more Jewish. October 7 brought up primordial anxieties in us alongside deep insights of identity that many don't know how to articulate in words, but the shofar's cry expresses for them the inner and national call. The understanding that those who attacked us on Simchat Torah went to war against our historical, religious, and national identity. About two weeks ago, in the lobby of a hotel in Washington, at a particularly bustling late hour with participants of the Israeli American Council (IAC) conference, I saw a shofar and without much preparation, I grabbed it and blew a tekiah, shevarim, and teruah. Electricity and anxiety filled the air.

Moses didn't leave clear recordings of what that teruah was, and thus two traditions emerged that are known today as "shevarim" and "teruah." The Talmud pointed to the Aramaic translation of teruah: "yevava" (whining). Who wailed in the Bible? Sisera's mother looked out the window, expecting her son to return with spoils from the battle against the Israelites. But her son was killed by Yael, wife of Heber the Kenite. And so it is described in the Song of Deborah: "Through the window she looked forth, and whined (" did yevava"), the mother of Sisera, through the lattice: 'Why is his chariot so long in coming? Why tarry the wheels of his chariots?'" (Judges 5:28). Here the opinions in the Talmud diverge, whether the yevava is a cry of "genuchei ganach," meaning broken sighs, or "yalulei yalil," meaning short and continuous wails. In practice, we sound both possibilities.

4.

What caught my attention in the Talmudic discussion is the learning of the nature of the main commandment in the first holiday of the Hebrew year, from the crying of the enemy's mother, be it Sisera, Nasrallah, or Sinwar! In the past year, when we heard descriptions of the atrocities committed against us by Hamas terrorists, the speakers said they were not worthy of being called human beings but animals and even less than that. But from our sages' perspective, even the bitterest enemy, be it Amalek or Pharaoh, remains human, and therefore we could demand that he bear responsibility for his actions and his hatred towards us, and thus pays for it.

Especially on Rosh Hashanah, which is called in our sources "Judgment Day," when God judges His creatures, and as the Mishnah says, "all the world's inhabitants pass before Him like sheep," no person can escape responsibility for his actions by claiming incompetence to stand trial. The Iranians and the death organizations under their patronage will also stand trial, and their fate will be similar. And so ends the Song of Deborah: "So may all Your enemies perish, O Lord! But may they that love Him be as the sun when he goes forth in his might. And the land was tranquil forty years" (Judges 5:31). We will read the epilogue about the tranquility of the land in prayer and request, that indeed this time it will be accepted, and truly may the passing year and its curses end, may the new year and its blessings begin. Happy New Hebrew Year.