"I can't say a bad word about the families of the hostages, as whenever they speak, they speak from the heart," says Avner Slapak as he reclines in his chair. "I remember how my father said to me, when I returned from captivity, that he had tried everything in his power to get me back. I was young then, not even a father myself, and I was unable to grasp the essence of the relationship between a father and his son.

"We were 12 men who were taken captive and only one of us spoke about the possibility of a prisoner exchange. All the others, including me, agreed that the bastards who had abducted us did not deserve the prize of having even a single murderer released in return for us. All the time we said, 'the government of Israel will ensure that we are released.'"

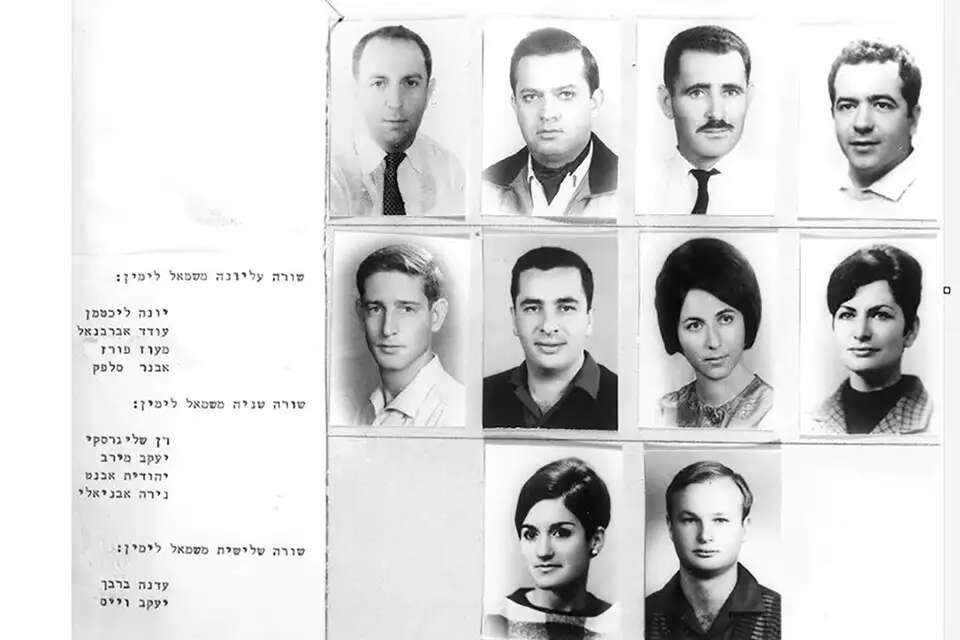

In the summer of 1968, Slapak, now 82 years old, was one of those abducted on the El-Al plane that was forced to land in Algiers, the capital of Algeria in North Africa. He was held together with an additional 11 Israelis for 39 days, until the government of Israel decided to release, in return for the return of all twelve, no less than 24 terrorists 'with no blood on their hands' – and thus to bring an end to the first airplane hijacking that occurred due to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

"On the plane, I planned to take an oxygen mask and breath through it, and the moment that the terrorist was dazed himself due to a lack of oxygen, I would be able to overpower him. I reached for the oxygen mask but the hijacker immediately cottoned on. He stuck the pistol in the back of my neck and said: 'If you move your hand once again, I will shoot.'"

"Until I got back home I did not agree that that any exorbitant price should be paid for my release," stresses Slapak. "It reminds me of something that Geula Cohen OBM said once when she was asked what she would do if her son was kidnapped. She replied: 'I will move heaven and earth to release him, but on the other hand I fully expect not to be listened to.'

"Today, I am clearly thinking about this even more. Should we betray the State of Israel? They might not understand me, they may think that I do not share the pain or that I don't care, as they say about 'Bibi', Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Believe me that I care much more than all those lefties together. You're a leftie too, right?"

I'm in the center.

"There is no center. That is an invention of the left-wingers. There is left and right, and don't say that it hurts me less than you."

We will get back to Slapak, who calls himself a "Bibist" or Netanyahu loyalist, and his political opinions, but first we should recount the background to the incident in which that airplane was hijacked, back in July 1968, and which since has largely been forgotten, paling into insignificance in the wake of the raid on Entebbe eight years later, possibly because in 1976 the hostages were rescued in a heroic military operation that inspired books and movies, while the hijacking of the plane to Algeria ended in Israel's surrender to the conditions laid down by the hijackers.

"It was a disgrace," laughs Slapak, "for abducted IDF soldier Gilad Shalit Israel released 1,027 terrorists, while they released a mere two for me (based on a calculation of 24 terrorists for 12 hostages – E.L.). Is that all that I am really worth?"

"I thought it was a drunken passenger"

Slapak was born in December 1941 in Beilinson Hospital, Petach Tiqwa; he grew up in Ramat Gan and completed his studies at the Agricultural School in Pardes Hanna. When he was recruited into the army he went straight to the pilot training course. "My parents were typically anxiety-ridden, neurotic Poles," he recalls. "I was scared to tell them that I was going to the pilot training course. I was on the course for six months and they had absolutely no idea, until the IAF invited the parents of the cadets to a flight in the sky above Israel – and at that point it was already too late and I was left with no choice. But then, they were actually really proud."

Slapak was the pilot of a Mirage fighter jet, he participated in the Six-Day War and took part in heroic moments during dog fights, but after the war, came an end to the action he had been looking for in the skies. "The victory in the Six-Day War was remarkable," he recalls, "but then after it we used to sit around in the squadron bored out of our minds. There wasn't a single plane in the entire Middle East that dared to take off. We thought that we had attained world peace and that our time in the military had now come to an end."

For many pilots, working for Israel's national airline, El Al, became almost an essential stage in their later career. Slapak had to undergo the transition from flying Mirage fighter jets to Boeing 707 passenger aircraft. On July 22, 1968, as a trainee pilot, he joined the crew flying flight El Al 426 from London via Rome to Israel. The captain was Oded Abarbanell, and the first office was Major (res.) Maoz Poraz, Slapak's colleague from the IAF squadron.

This was due to be Slapak's last flight as a trainee pilot, and Abarbanell, the chief pilot who was training him, said that as far he was concerned Slapak could already be considered as a regular pilot. Essentially, it is the trainee who actually flies the plane, alongside the captain, with the first officer supervising from the seat behind them.

The flight to Rome went by without any problems, and the plane then took off on its homeward leg for Israel during a nighttime flight. "There was total silence," Slapak recalls. "The radio channel was quiet for the most part, apart from the American pilot of an Ethiopian Airlines flight that was flying not too far away from us, and he just didn't stop talking. The cockpit was dark, so that we could see what was going on outside.

"Suddenly, I heard noises from behind. The door separating the cockpit from the passenger cabin was open, it was a regular door rather than the hardened flight deck doors in service today. At the time, talk had just begun about the danger of hijackings, and the funny thing is that the Shin Bet (Israel's Security Agency) had actually issued a directive to shut the door – but only when the plane was east of Athens. You see? We were flying with the door open as we were still to the west of the Greek capital. Okay, so you learn from experience."

"At the site where we were held there was hardly any food, and they didn't let us move without a guard standing close by. At some point the negotiations progressed, so they moved us to a luxurious villa in the city, including a cook and a bar with the most expensive drinks. They wanted us to say that we had been treated well. It didn't take them long to return us to the terrible conditions we had endured beforehand"

Slapak looked back to try and understand what the cause of the noise was, and then he became aware of the stewardess, Yehudit Avnet, struggling with one of the passengers. "I was sure that this was just a drunk who wanted to enter the cockpit," he recalls, "I told her: 'Get him out of here,' and then all of a sudden he produced a pistol.

"Maoz Poraz, who was sitting next to me, slapped his hand in an attempt to knock the pistol out of his hand, but he failed to do so. In response, the terrorist pistol-whipped him hard on the head and Maoz lay on the floor bleeding profusely. I was 26 years-old, I believed that I was a hero, and I thought to myself, is this what they do to someone who has just conquered half of the Middle East? I said to Abarbanell 'take the sticks' and I released the seatbelt with the intention of trying to take out the terrorist.

"Suddenly, I saw the barrel of a pistol in front of my eyes. The terrorist squeezed the trigger, releasing a shot – and I stopped. I felt hot spots on my forehead. I concluded that this must have been a blank, but later on it transpired that I was wrong. The bullet simply hit the light above my head and the shards flew everywhere. But at that moment I was convinced that he had fired a blank, and I felt that I had nothing to fear.

"I tried to get closer, but the terrorist aimed the pistol at me and once again squeezed the trigger. This time the gun jammed. He tried to clear the jam, and suddenly I noticed that he was holding a hand grenade. Now go and take him on. I sat back down in my seat."

"It was the Holocaust survivor who calmed us down"

Slapak recounts that apart from the terrorist in the cockpit, there were two more of them among the passengers, members of George Habash's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), an organization, which at the time was stepping up its spectacular terrorist activity with the aim of "shoving the Palestinian problem down the world's throat." The leading terrorist knew what he was doing. He was familiar with the flight path and knew by which control towers the plan was due to pass. He didn't tell the Israeli pilots that their final destination was in fact Algeria.

"At some point the control tower called us: 'El Al, what is going on with you?'", Slapak continues. "The terrorist replied 'This is not El Al, this is an 'Al-Asfa' plane, we have been given instructions to fly to Algiers – and the air traffic controller didn't understand. Then, the American pilot of the Ethiopian Airlines flight, who was flying close by, told the air traffic controller on the radio 'Don't you understand that this is a hijacking?'

Yonah Lichtman was the flight engineer on board the flight. I told him: 'Take up the plane to high altitude,' so that the air pressure inside the cabin would go down, and this should cause everybody to lose consciousness. "My plan was to take an oxygen mask and breath through it, and the moment that the terrorist was dazed – I would overpower him. At that time, this was how we used to wage war, by improvising. So, I reached for the oxygen mask but the hijacker immediately cottoned on. He stuck the pistol in the back of my neck and said: 'If you move your hand once again, I will shoot.'"

Q: Weren't you afraid?

"What is really amazing is that I wasn't afraid even for a single moment. Just as during battle, there is a rush of excitement and adrenalin before you engage the enemy, and then suddenly everything is calm and quiet. You do what you have learned. The terrorist, on the other hand, was extremely excited. I was afraid that he might shoot at us out of pure pressure. Abarbanell tried to calm him down while flying the plane, he talked with him as a mother talks to her son.

"After a few hours, we landed in Algeria. All the time, I remembered that in my wallet I kept an IAF crew member's card. I needed the card on a routine basis to enter the base, and also, at that time, if a cop would stop you for speeding the IAF card would be sufficient to prevent you getting a fine.

In Algeria, I didn't want anybody to know that I was an IAF pilot. So, as soon as we landed and turned off the engines, I took advantage of the moment that the plane was without power, before they had time to reconnect it from an external power source. In the second of darkness that I had, I took out the card and threw it into a slot in the instrument panel. I then calmed down."

Once the plane landed in Algeria, the Palestinian terrorists took a back seat and passed over command of the incident to the Algerian security police. The women and children on board, along with the foreign nationals, were released, and the hijackers kept the remaining 12 Israeli males – seven crew members and five passengers – hostage as a bargaining chip. They were kept at the security police base near to the airport.

"If I knew that our current captives in Gaza were in the hands of kidnappers like the Algerians, then today I would be at ease," says Slapak. "They were nothing like the Hamas Nazis. It didn't take me long to realize that they were in way over their heads. They had not planned for us; they didn't want us and above all they were angry at the Palestinians.

"On the day we landed back in Israel, the IAF commander, Motti Hod, hugged me and said: 'Had they decided to hold you for another few days, we already had a plan to extract you.' Afterwards, I came to realize that they took the outline of the rescue operation that was intended for us to form the basis of the raid on Entebbe in 1976."

On the first day, their sergeant major, who was in charge of the guards, told us 'Don't worry, everything will be fine.' He said that if Algeria's ruler at the time, Houari Boumédiène, would have wanted to kill us, we would never have even set foot on Algerian soil. They would have shot us on the aircraft boarding stairs."

Q: Did you believe him?

"There was concern and there were disagreements among us. There was one, whose name I shan't mention, who scared us. He said that at best they would execute us by shooting, but he thought that they would not waste bullets on us, so they would do it by hanging. One of the passengers felt ill once he heard that, but most of us were not afraid. We had the confidence that everything would be okay."

A protest hunger strike

In Israel, in the meantime, a drama was unfolding during those fateful days. The newspaper headlines dealt with the hijacking, and the Minister of Transport, Moshe Carmel, said from the Knesset podium: "The Algerian government's conduct is essentially sponsoring skyjacking and lending a helping hand to dangerous gangsters on international air routes, and this is something that both we and the civilized and cultured world cannot tolerate.

"The Government of Israel stipulates that the people of Israel will in no way accept the fact that the Government of Algeria shall continue to hold the hijacked plane and its people, and neither will it be disconcerted by the intentional playing for time nor surrender to acts of blackmail. It is Algeria's absolute and unconditional duty to release the aircraft.

"Anybody who lends a hand to these barbaric acts that turn international air travel into a real jungle, should know that we shall use all the means at our disposal to protect the means of transportation to and from Israel, and shall do everything in our power to deter those gangsters who seek to sow anarchy around the world."

"We did not have good conditions at the base where we were held," Slapak recalls. "There was hardly any food and the guards wouldn't let us move without their close attention. I remember that I was sitting on the toilet and the entire time there was a guard there with a pistol aimed at me. I am sitting there, he is sitting opposite me, until I told him 'I no longer have the will to do this.'"

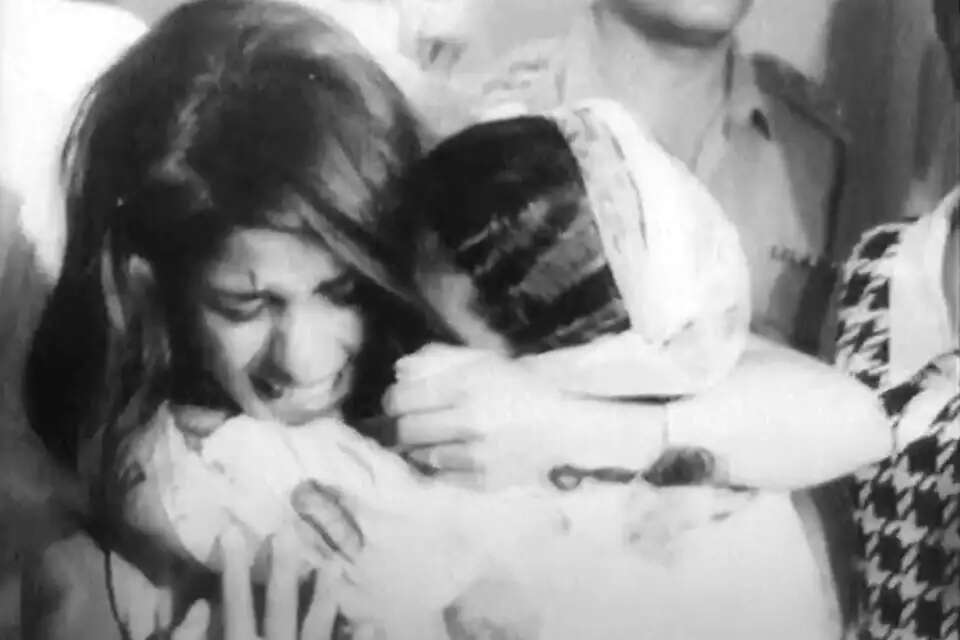

Sarah, Avner's wife, sits next to us in the lounge during the interview. The couple were already married when Avner was taken hostage, and Sarah was in an advanced stage of pregnancy in Israel. "It is nothing like the situation today, as at that time there was no media or communications and we knew nothing about the fate of the hostages," she recalls.

"Once every two weeks, the wives of the hostages would meet up, and somebody would inform the captain's wife if there were news. They tried to constantly calm us down 'it will be alright, there are ongoing diplomatic negotiations.' But pressure? At home we didn't even have a phone, never mind a television. Today there is too much media – 'a deal is on, there is no deal.' We remained silent."

Slapak recounts that the Algerians took each of the hostages for questioning, but it was neither threatening nor aggressive. "I am not an orderly or organized person," he laughs. "I had an El Al bag, and Sarah can testify to the fact that I used to throw everything in that bag. So, the interrogator took our papers from the bag, he examined a letter from El Al that he proceeded to question me about.

"Afterwards he took out a letter from the IAF squadron about a special exercise that they wanted me to take part in. He looked at it, folded it and threw it in the trash can. When the IAF commander, Motti Hod, met me immediately following our release, he told me that the Egyptians had asked the Algerians to interrogate us if we were IAF pilots, so the Algerians said 'Give us material that we will be able to use to corroborate this with them' – and the Egyptians said that they didn't have any. This goes to show that the Algerians had no intention of working on us."

The negotiations for the release of the hostages went on and on. The hijackers, with mediation by the Algerians, insisted on the release of terrorists in return for the hostages, the Israeli government refused – and the world tried to mediate via diplomatic channels. "There were apparently advanced negotiations to find a solution, so one day they transferred us to a luxury villa in the center of town," recalls Slapak. "You can't imagine what conditions we were now given. Suddenly there was a chef, a bar with all the most expensive drinks that I would never even fantasize about ordering at a pub.

"They did all this so that afterwards, we would say that we were treated well. It was like that for about three or four days, until the talks hit a brick wall – and then they returned us to the base near the airport, and here we were soon back to the terrible conditions we had endured beforehand. I remember being constantly hungry, after we decided to go on a hunger strike in protest, for as far as we were concerned this was a decline in conditions. The Algerians were apparently taken aback, so they ordered food for us from Air Algeria. Hamgashiot (disposable airline meal trays) as people today like to call them."

Q: What were the relations like among you, the 12 male captives?

"They were fine. The person who made the greatest impression was Yonah Lichtman, the flight engineer, who was a Holocaust survivor. From time to time, when one of us would be overcome by a sense of acute anxiety, Yonah would calm us down and say 'Guys, what the Nazis did to me the Arabs cannot do. Don't worry, I am here.'"

"Go and shave, you are about to be released"

The captivity ended after 39 days, without any prior warning for the hostages. "While in captivity, we began to grow beards, Slapak recalls and laughs. "I was sporting a black mustache and a ginger beard, so I shaved it all off. In the end, everybody became fed up with it so they shaved, apart from Elkana Shamen, who kept his beard. An Algerian officer came and asked, 'Why haven't you shaved?', and Shamen replied: 'I will only shave once we have been released.'

"On one Shabbat, without any prior warning, the officer came and told Elkana 'Go and shave.' Shamen answered him 'I have explained to you that I will only shave on the day that we are released.' So the officer repeated: 'Go and shave.' We understood that we were about to go home and there was a tremendous feeling of joy and happiness."

The released hostages flew to Rome and then from there on to Israel. Sarah, a young woman who came to meet her returning husband while in an advanced stage of pregnancy, remembers how she was forced to contend with hordes of journalists who came to the airport in Lod. Was the State of Israel about to release the hostages in a military operation? In his book, Hoy Artzi Moladeti (Oh, My Country, My Homeland), published in 2015, Colonel (res.) Eliezer (Cheetah) Cohen went on to write about the operation to release the hostages that had already been planned, prepared and drilled, and according to Cohen, it was called off at the last minute after the then Minister of Defense, Moshe Dayan, got cold feet.

"Post-trauma? At that time, there was no such thing. But every time I would see a prison movie or barbed wire – I found that to be an extremely difficult experience. It is for this reason that I say that it will take years, if ever, for the hostages who will hopefully return from Gaza, until they are able to laugh at such things. I can only imagine that they are suffering terribly."

According to Cohen, who at the time commanded a force of six Bell-205 helicopters, the operation was due to take place in a number of stages: silent infiltration into enemy territory, a raid on the location where the hostages were being held, taking out their guards and then flying the hostages to an Israeli ship waiting in open sea. There, Cohen wrote in his book, they were supposed to arm the helicopters, which were then to fly back to the international airport in Algiers and destroy the national airline, Air Algeria.

The helicopters were then to return to the Israeli ship, from where it was due to continue its voyage to the Netherlands. The combat operators taking part in this operation were then due to return to Israel as regular tourists on an El Al flight. "Had Dayan given us the green light to stage the operation, just like the drill on the model, which was conducted in the presence of the Chief of the General Staff, it would have been an overwhelming success," wrote Cohen. And by the way, the French press also reported that when the plane was on the ground in Algeria, a group of Israeli James Bonds is making plans to rescue the hostages.

Slapak has his own version of the events: "On the day we landed back in Israel, the first person to come and meet me was the then IAF commander, Motti Hod. He hugged me and said: 'Had they decided to hold you for another few days, we already had a plan to extract you.' Afterwards, I found out that they took the outline of the rescue operation that was intended for us to form the basis of the raid on Entebbe, so that it didn't take long to prepare for the Entebbe operation in 1976.

"In our case, they didn't cancel the operational plan, they simply succeeded in bringing us back home before it was time to put the plan into action. I remember that Elkana Shamen woke me up one night due to noises he heard, as we were constantly convinced that IDF's elite Sayeret Matkal commando unit would arrive at any moment, as we were sure that the army would not sit idly by. As I said, we were totally against any prisoner exchange deals."

Following the hijacking, and additional terrorist attacks that were later aimed at El Al aircraft, Israel began to implement a meticulous security check program as well as security measures on its commercial flights. The hijacking predated the establishment of the civil aviation security unit, which was run by Shin Bet, and contributed to the formulation of an established set of rules for conducting negotiations with terrorists along with preparations for hostage rescue and takeover operations to be carried out by special forces.

In addition, the IDF embarked on a reprisal operation, Operation Gift (Mivtza T'shura in Hebrew), in which passenger aircraft belonging to Arab airlines were destroyed at Beirut International Airport, after information revealed that the terrorists who had hijacked the El Al plane and abducted Slapak and his colleagues had set off from Lebanon.

Nothing but admiration for today's combat soldiers

All those who were with Slapak in the cockpit on the day of the hijacking are no longer with us, or as Slapak puts it: "They are flying in another world." Abarbanell OBM, who was the flight captain, passed away two years ago at the age of 96, while Maoz Poraz OBM, was killed in the Yom Kippur War when his plane crashed over Sinai on October 17, 1973.

His son, Captain Nir Poraz OBM, was a Sayeret Matkal officer who was killed in October 1994 during the botched attempt to rescue Sergeant Nachshon Wachsman OBM, a young soldier who had been kidnapped by Hamas. Slapak returned to flying for El Al, and in fact he worked as a pilot there until his retirement.

Q: Over the years did you experience flashbacks from the hijacking?

"Today, people tend to speak about post-trauma, but at that time, there was no such thing, just as smoking cigarettes and exposure to the sun were not considered to be dangerous then. But every time I saw a prison movie – it would startle me and make me jumpy. Or, for example, I went with my wife to the movies only a few days after my release and there were barbed wire fences in the movie, I found it difficult to look at them. It is for this reason that I say that it will take years, if ever, for the hostages who will hopefully return from Gaza, until they are able to laugh at such things. I can only imagine that they are suffering terribly."

Slapak sits at his home in Moshav Ben Shemen, not far from Ben Gurion Airport, and he has no doubts as to what should be done now with the current hostage situation. As far as he is concerned, he relies on the prime minister to guide us back to safety and stability.

"I am no great expert in Judaism, although I have a son who is a ba'al teshuva or newly-religious, but now since everybody has started talking about pidyon shevuyim, the mitzvah to redeem captives or hostages, I began to read up on the topic," he explains. "It is true that pidyon shevuyim is a great mitzvah, and our sages said that an individual must do everything in his power to redeem his wife, but as far as the state is concerned – it must do what is necessary to redeem captives, but not pay an overly exorbitant price. The sages explain this by saying that it is forbidden to encourage bandits from kidnapping more people, and this is something that you simply do not hear today. What does it mean 'everything'? Does it include giving up the state?

"I have heard one of the bereaved fathers say: 'Those who are prepared to give up everything, are they prepared to exchange their children with the hostages?'. We should be prepared to give up a lot, but if we agree to end the war and Yahya Sinwar returns to ruling over the Gaza Strip, then the State of Israel will be lost. There will not be a single Jew, either in Israel or around the world, who will be safe from abduction.

"They will be arming these callous murderers with the ultimate doomsday weapon, more than an atomic bomb. I have nothing against the families of the hostages who are constantly out there screaming and shouting. That is okay, I am really sorry for them. I feel deeply for them, but Bibi's brother was also killed during the attempt to rescue hostages, so he doesn't want them to return home?"

Q: Many people claim that the prime minister is simply trying to survive politically.

"Oh, do me a favor. His real political survival lies in bringing back the hostages. If he were to bring them all back, he would secure reelection for another 20 years as prime minister. He is much cleverer than anybody else in politics right now."

Q: Are you a member of the Likud Central Committee?

"I actually used to be a member of the Labor Party. I was a card-carrying, paying member. I used to go along with Yitzhak Rabin, and whenever my friends ask, 'How can you go along with Netanyahu?' I answer: 'The Labor Party, when I was a member, was more to the right than today's Likud party.'

"Who was it that expelled hundreds of Hamas terrorists to Lebanon, Bibi? They say, 'We are Rabin's legacy,' and I say 'You have no idea what Rabin's legacy is. You are inventing a completely new legacy.' I get on just fine with my left-wing friends. Why should I lose those who fought beside me because of political opinions? Never. If they decide to lose me, that's something else entirely."

Q: It is remarkable that you are still in favor of the prime minister after October 7.

"I do have a score to settle with him, but we will settle everything after we bring back victory and then there will be elections. I believe that new leaders will come forward after the war, just as they did after the Yom Kippur War. The heroic fighters in Gaza are the ones who will lead the people, I have nothing but admiration for them. Until this current war, my grandchildren used to say, 'Our grandfather is a hero,' but we are nothing compared to them. What fighters."

Avner, who after the hijacking served in the Yom Kippur War and the First Lebanon War in 1982, has two grandsons serving in the current combat. Iddo, Avner's son, returned to reserve duty as a 54-year-old volunteer, and he repairs D9 armored bulldozers that go into action in the Gaza Strip.

"Our country has a great future ahead of it," Slapak is convinced. "I hear how my grandchildren speak, what a fighting spirit they have. In one of the wars, I was lying on the bed in the standby room, ready for the squadron to be scrambled, and I was reading the newspaper. I remember how I started laughing all of a sudden, and then someone asked, 'What's the matter?' I said to him 'It's written in the newspaper that if you don't have a son on the front line – then you have no idea what war is all about.' It was only after my children joined up that I stopped laughing."