Shai Davidai is an Israeli-American social psychologist, senior lecturer at Columbia Business School and symbol of the fight against the new antisemitism in American academia.

Q: Let me begin with a question I ask every Jew I have met since Oct. 7: How are you?

"That may be the hardest question there is. Right now, on Wednesday at 10 a.m., I'm fine. Tonight, a demonstration is planned against Hillel [an organization to strengthen Jewish identity on campuses] at Baruch College, and I am planning to go and support the Jewish students who will be facing the demonstrators, so I guess if you ask me tonight may give a different answer. I usually come back from these events mentally drained, it really hurts to experience these attacks. But then I attend events with Jewish communities – for example, today I'm supposed to be talking to a congregation from Montreal on a visit here, and yesterday I was in Philadelphia –that fills me and lifts my spirits. We are in a period that is quite simply a rollercoaster, mentally and physically, and apart from everything that's going on with me personally, I'm obviously connected to what's happening in Israel."

Q: You were one of the first people to recognize that this time, just days after the massacre, something different was happening on campuses. In a video that went viral, you appealed to Jewish parents across the United States and warned them that their children were no longer safe on campuses. Tell us a little about this realization: How did you come to see that this was an exceptional event and what made you stand up and act?

"If it wasn't me, someone else would have stood up. Columbia was one of the first universities to see violent demonstrations, and as it happened, I had a front-row seat. Until then, I had never experienced anything like what I saw. For years there have been demonstrations by pro-Palestinian movements, but they have always been on the fringes, and now, suddenly, it was happening in the heart of the campus, without any attempt to hide it or tone it down. I wasn't planning on giving a speech, it was a spontaneous cry from the heart, because I felt I had to say something."

Q: Does it have anything to do with the fact that you're Israeli and that comes with the self-confidence, the unwillingness to lower one's head until the storm passes?

"I can't judge a Jew who has been told all his life, 'Forget it, antisemitism has always been around and it always will, don't make a thing of it, don't fight, don't ask the management for anything,' and suddenly, when he's 19 years old, people expect him to get up and fight. But it also has to do with character. I never had much reverence for authority."

Q: After the video went viral, you became a target. There are memes on social media, including some imitations that make you laugh, but there are also curses and threats. Were you scared at any point?

"For the first few weeks, I didn't leave the house. I experienced a real physical fear, at least until things calmed down a bit here and I calmed down too."

Q: You walk around with a big black Star of David pendant, and a look that combines a nerd in glasses and a rocker with tattooed arms. Alongside the hatred directed at you, at pro-Israel demonstrations people call you "Am Yisrael Chai" and ask to take a selfie with you. You have become a star of Israeli hasbara, and you have even testified before Congress on the issue.

"Hate and love are strong emotions, and they need someone to project their emotions on. For many Jews in the United States, who have felt and may still feel lost and afraid, it helps to have a face and a name they can project their feelings on. On the other side, too, people who hate and are angry without even knowing why project all these emotions on me."

Q: Sounds rough. How do you survive that?

"As soon as I realized that I was just a symbol, an object of projection, that made things easier for me. The fact that people hated me, really hated, without knowing me was something that really confused me. It took me a long time to deal with the fact that they didn't actually hate me. I had to develop a thick skin because I'm a sensitive person. It was hard, it injures the soul."

Q: Did you have campus security at any time?

"No. Yarden, my wife, asked me to go to the police, but they said there was nothing they could do. For me it was more of a psychological thing – I was worried that it would somehow affect my family life, my children and my wife."

The masked masses

Q: You've been living in the United States for 14 years. You studied at Cornell and Princeton, you teach at Columbia, and you are intimately familiar with the Ivy League universities. Your research deals with the forces that shape and distort worldviews and their influence on our judgment, preferences, and choices. As an expert, give me your intellectual analysis of what's happening here.

"At the most basic level, the hatred we are witnessing has to do with the fact that these students act on masse and cover their faces, with a keffiyeh or a mask. They are literally going through a process of de-individuation, which allows them to spew out evil. These are really signs of a cult."

Q: What you are saying was very much evident in videos in which we see protest leaders shout out a slogan and the crowd repeats it like a bunch of zombies. What happens to these people when they leave the group framework and go back to being individuals?

"When I met the student protestors one-on-one, they were nice and polite. Something about the herd mentality and being masked allows the protestors to drop all the normative barriers."

Q: So wearing masks is not only intended to make it difficult to identify the protestors, but is in fact an essential part of the psychological mechanism that leads to this abandon. We see the same process on social media: anonymous people tend to speak in more polar and negative language.

"We've seen this throughout history, not just in this current era. During the pogroms, or Kristallnacht, for example, it was always the mob. That's part of it. I've always been fascinated by the stories of 'the SS officer who saved me': it was always a single person and it always seemed strange to me, but that's how we're built. Individually, everyone is nice and good, but in a group setting they become part of an ideology."

"Columbia was one of the first universities to see violent demonstrations, and as it happened, I had a front-row seat. Until then, I had never experienced anything like what I saw."

Q: And in a deep sense, why do people have a need to run with the herd? What does this give us?

"I think historians who write in the future about the current period, will, with the perspective of time, point to several factors that caused this storm. There was COVID-19, a global pandemic – a shocking event that created a lot of waves; a second factor is growing inequality in the Western world, particularly in the United States, from economic, ethnic and racial perspectives. Moreover, this is a generation of young people who will be less financially successful than their parents. In recent decades, every generation has improved its status relative to its parents, but now this has come to an end. The combination of all these factors increases social alienation and causes young people to search for belonging and meaning. And suddenly a movement comes calling on them to join and all they are required to do is wrap themselves in symbols and shout. And this is a movement that is not for but against. It is well known that it is much easier to employ hatred and anger rather than love to get the masses out on the streets."

Q: One could argue with that. The big hippie protests in the sixties were motivated by free love. Even Hitler used positive slogans like "Germany above everything."

"True, but that slogan also included hate speech based on racial theories and German supremacy. The hippies began as an anti-war movement that advocated counterculture, and when that struggle ended, they began to collapse. The Black Lives Matter movement has also existed since 2015 but only erupted in protest against police brutality after the killing of George Floyd. And now they are anti-Israel, anti-Jewish and anti-Zionist. Their existence is contingent on our non-existence."

Q: You have said that this is connected to class gaps, but we see a lot of spoiled, rich young white people joining the demonstrations.

"Protests are a lot easier and much more fun than going to class. Also, when your parents can pay bail and the cost of the extra semester you'll have to study then you don't have to be afraid of being arrested or suspended from school. Anyone paying $30,000 out of their own pocket won't do that."

Q: That may explain why students are getting carried away, but what about the faculty who are leading the struggle?

"For years, academics have been engaged in building the theoretical foundations by generating hatred, brainwashing and building ideologies. It's reminiscent of the early stages of the Nazi movement."

Q: You draw a lot of comparisons to Nazi Germany, even though some people consider such comparisons taboo.

"I have no intention of degrading the memory of the victims and the heroism of the survivors, quite the opposite in fact. I do so to understand. My assumption is that the Holocaust was an extreme event, but not a unique one. The story that the world is telling itself, that it was an extraordinary event, is false. The only reason to study history is to understand the present."

Q: Doesn't this lead to us always preparing for the previous war?

"We have no right to think that this time it will be different. I'm not saying that we will see history repeat itself, but historical comparisons to the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, Kishinev or the Dreyfus trial help us understand what is happening, and at the same time help us understand what can happen if we don't act. Keep in mind that most Americans don't learn about the Holocaust. Only twenty states out of fifty require Holocaust studies, and children learn only about the end, the ghettos and extermination. They don't start in 1923 and they don't learn about the processes that occurred. So, when we say, 'Never Again,' they need to understand what we mean."

Q: Interestingly, the modern basis for race theory, eugenics, developed in American academia at the beginning of the 20th century, as the applied facet of genetics, long before the Nazis adopted the theory.

"That's correct, but the Nazis took this theoretical foundation and turned it into practical policy. Soviet Russia, too, used academia in the humanities and social sciences to provide justification for its actions. The same is true in present circumstances: academia invented anti-colonialist theories and uses them to fight Zionism. So, when you want to take an 18-year-old and make him shout, curse and single out Jews on campus, you can give him a theoretical justification. Today, we call it 'social justice,' in the past it was known as 'anti-imperialism,' and before that 'racial purity.' They are all the same – quasi-academic theories designed to excuse Jew-hatred."

Q: In the end though these arguments don't hold water. For example, the claim that Israelis are white occupiers. If you look at Israel's ethnic demographics this is easy to refute.

"First of all, they don't look. It's much easier to spout nonsense when you don't look at the facts. Second, they invent theories."

The death of discourse

Q: Apart from the liars and haters and those who speak in slogans and clichés, isn't there anyone in academia with whom you can conduct a productive intellectual discussion? Are there no serious people, PhDs and professors who are supposed to specialize in the field and understand history?

"Nobody sat down to talk with me."

Q: No one?

"Absolutely not, but one of the basic arguments of this group is anti-normalization. To be interviewed by an Israeli newspaper is to legitimize Israel. To invite an Israeli lecturer, even if he even comes to talk about physics, or to engage in dialogue with someone who is not Israeli who supports Israel is to legitimize Israel."

Q: In other words, we are talking about a silencing mechanism. "The Cancelling of the American Mind" a book by Greg Lukianoff and Ricky Schlott which came out in October exposed the mechanisms behind cancel culture. They point to destructive methods of argument such as whataboutism, gaslighting, denial, downplaying of real problems and the use of emotional blackmail.

"Exactly. This not only silences the other side but also makes you feel morally superior to them."

Q: Is there no way around this?

"There are intelligent people who are supposedly open and enlightened, like the historian Rashid Khalidi. I haven't seen him hold a debate, but I think he would talk to me. His indoctrination is not through lies but by hiding the truth. But there are also liars. I had a conversation with one of the protest leaders. Forget that everything he said was rife with conspiracy theories, such as the claim that Israel killed the revelers at the Nova music festival, or that there no rape took place. I asked him, what about the hostages, you can't deny that because Hamas publishes videos of them. He answered me with whataboutism: What about the babies that Israel kidnapped? Or, for example, he claimed that Hezbollah will stop firing at Israel when Israel ends its occupation of Lebanon."

Q: What did he reply when shown that there is no Israeli occupation of Lebanon?

"He changed the subject. They don't let the facts throw them off track."

Q: Dr. David Barak-Gorodetsky wrote in Makor Rishon that when he taught a course on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at the University of Chicago, he discovered that students were not at all interested in actual history – in what happened in 1929 or 1948. Conceptualization was more important to them– colonialism, apartheid, ethnic cleansing. Once you have a category – good or bad, oppressor or oppressed – the story is over. Shouldn't academia be based on truth and facts?

"Theoretically, yes. But in reality, there is a move to the method of indoctrination, learning through the transmission of opinions and beliefs. We are experiencing this right now, directed against us, but this is not something new and the world will see this in many fields. For example, it is difficult to say anything in academia contrary to the consensus on global warming. This can be more about opinions than research and scientific facts. If you want to be part of academia you must believe that global warming is real. In other words, you have to first believe and then investigate, instead of first researching and then drawing your beliefs from that research. That's indoctrination.

Soviet Russia, too, used academia in the humanities and social sciences to provide justification for its actions. The same is true in present circumstances: academia invented anti-colonialist theories and use them to fight Zionism.

"There has been no discourse in academia for a long time. There are legitimate opinions and opinions that are not legitimate. Opinions determine research rather than research determining opinions. In many fields in academia that's not the case, but in faculties that touch on political or contemporary issues, this really stands out. That's why all research on stereotypes and prejudice focuses solely on gender, sexual preferences or skin color, because these are the things that society is involved with. But all the people who claim to be experts on stereotypes have never explored the oldest prejudice in the world – antisemitism."

Q: Jews don't count, as British comedian David Baddiel observed in his book of the same name. Jews are the only minority not afforded protection under the umbrella of minority status.

"That's exactly the point. You'd think academics would say, for example, let's investigate hate crimes in New York State. After all, there is solid factual data on this. In the past seven years, between 45 and 55 percent of hate crimes there have been against Jews. More than any other group – gays, blacks, women, Muslims. Why doesn't this trouble anyone in academia? Because it's mostly in Brooklyn, mostly Jews with shtreimels, wigs and tzitzits. That doesn't interest them."

Q: We see amusing videos of protestors who don't understand what they are protesting about, who don't know what river and sea they're singing about. Are they typical of the majority of the protestors?

"It's hard to know, because the organizers don't let the demonstrators speak. People need to understand that this is a cult. At all the demonstrations there are representatives keeping an eye on the protestors. Where else have you seen a demonstration where the media can't interview protestors? They are told not to answer questions, and there is a reason for that: most of the demonstrators are ignorant or will give embarrassing answers."

Q: Who are these people who do not allow protestors to answer questions? It sounds like the Illuminati.

"They are the organizers, the leaders. I agree that it sounds insane that people aren't allowed to talk."

Q: Some universities have dealt decisively with protests and riots, for example, in Florida. What can we learn from them?

"Very few acted in that way, mostly public universities in states with Republican governors. It served their agenda; they took advantage of the situation to attack progressives."

The cost of boycotts and the price of silence

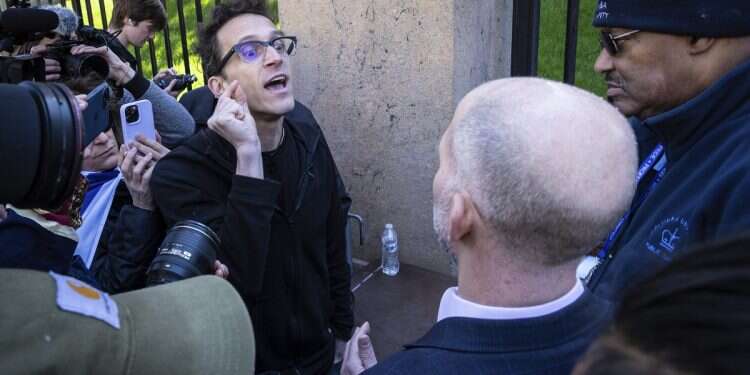

Q: Your high profile led to the university administration opening an investigation against you and blocking you from entering its gates. Where do things stand with this?

"Still under examination. The university is trying to find a way to get rid of me. At first, they tried to ignore me and let the problem resolve itself. Then they tried to silence me during the investigation, but I quickly made everything that had happened public and showed them that they would not succeed in silencing me – quite the opposite. When they blocked me from entering the campus, that was already a signal to everyone else, to make sure everyone saw, to make sure that other lecturers do the math. In that sense, they succeeded."

Q: The affair could end your academic career, which you worked so many years to achieve.

"True, but the price of silence is much higher."

Q: We are seeing Israeli researchers returning to Israel because of the situation. Have you thought about that?

"I guess that will happen at some point. You know, it's not easy to go back to Israel now. Israel's future is unclear, the future of Israeli academia is unclear, the future of Israeli democracy is unclear, and the future here is unclear too. It's hard to decide. And I also have a role here. I fear the world's goal is to turn Israel into the largest ghetto in history. They will impose boycotts and sanctions, they will starve us, metaphorically. We know how every ghetto ends. What worries me is that we are not returning out of choice but out of no choice. I want to make Aliyah out of love and free will."

Q: That's a little naïve. The mass Zionist migrations began when Jews were pushed out by pogroms and economic hardship.

"It is true that the masses are motivated not by ideology but by necessity. However, I would like to see all decisions, not necessarily just those concerning migration between countries, but also for example deciding between universities to be a matter of choice. That people will leave Harvard not because they're afraid, but because they've found a better place."

Q: A silent academic boycott of Israel and Israeli researchers already exists, and it is becoming more and more out in the open. What are your thoughts on that?

"The first to pay the price were academics in Israel, both Jews and Arabs, because the boycott is against Israeli academia. But publications by Israelis who study in the United States and have a resume of studies at Israeli universities are also rejected."

Q: On the other hand, we are witnessing unprecedented donations to Israeli universities. A few weeks ago, Bar-Ilan University received a one-billion-shekel donation from the estate of an anonymous donor who graduated from Columbia; it was the second-largest-ever donation to Israeli academia. The University of Haifa received a donation of NIS 200 million.

"I don't know how long this will last. In any case, academic collaborations with institutions overseas are critical for the development and progress of researchers. There is no financial alternative that can make up for this. I don't think Israeli academia and the Council for Higher Education have internalized just how problematic this is. The $260 million that Bar-Ilan received is amazing, but it's a reaction to the problem instead of a solution."

Q: In conclusion, is there anything you would like to say to our readers?

"I have never seen Diaspora Jewry so close, so strong and, after many difficult years of estrangement, so connected to Israel. It's a huge opportunity. After October 7, it is clear to world Jewry that it cannot exist in security without Israel. I think it should be clear to the State of Israel that it too cannot exist without Diaspora Jewry. We in Israel experienced a critical moment and world Jewry responded. Israel must internalize this and embrace all Jews. I'm not sure we'll have another opportunity like this.

"The second thing people need to understand is how cohesive the Jewish world is right now. It may sound funny, but in recent months I have spent more time in synagogues than in the previous 41 years of my life. Not to pray but to meet, talk and have dinner. I spent the second Passover Seder with Chabad. The Jewish community is growing stronger and stronger, and everyone's connection to Judaism has grown stronger. It is a rare and beautiful moment."