Zurich's prestigious Kunsthaus Zurich art museum has announced the temporary removal of five paintings from its ongoing exhibition showcasing the Emil Bührle Collection. This decision comes as the institution investigates potential links between these artworks and Nazi-era looting during World War II.

The collection, named after German-born Swiss industrialist Emil Bührle, has long faced scrutiny regarding the provenance of its holdings. Bührle amassed a vast collection of approximately 600 artworks, many of which were acquired during the war years when the Nazis systematically plundered cultural treasures across Europe.

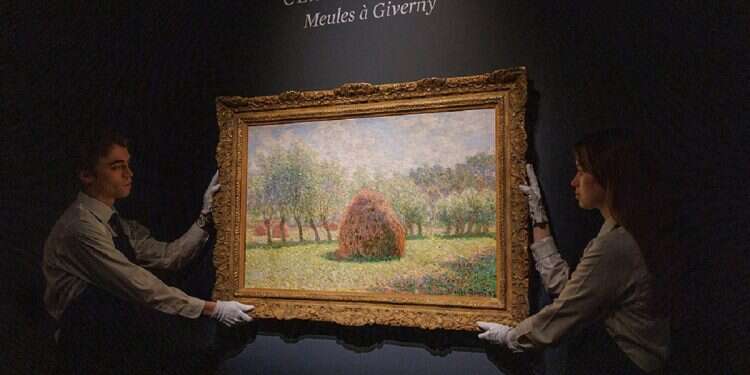

The artworks under investigation include renowned masterpieces such as Claude Monet's "Jardin de Monet à Giverny," Gustave Courbet's "Portrait of the Sculptor Louis-Joseph," Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's "Georges-Henri Manuel," Vincent van Gogh's "The Old Tower," and Paul Gauguin's "La route montante."

In a statement, the foundation board overseeing the Emil Bührle Collection expressed its commitment to "seeking a fair and equitable solution for these works with the legal successors of the former owners, following best practices." According to Stuart Eizenstat, the US Secretary of State's special advisor on Holocaust issues, it is estimated that over 100,000 paintings and countless other cultural objects stolen during the Nazi era have yet to be returned to their rightful owners or heirs.

The decision to temporarily remove the paintings follows the publication of new guidelines aimed at addressing the persistent issue of unreturned cultural property stolen during the Nazi regime. These guidelines were developed by the US State Department to mark the 25th anniversary of the 1998 Washington Conference Principles, which outlined a framework for the restitution of Nazi-confiscated art.

While the foundation board acknowledged the potential application of these guidelines to the five artworks in question, it stated that a sixth work from the collection, Edouard Manet's "La Sultane," would be considered separately. The foundation expressed willingness to offer financial compensation to the estate of Max Silberberg, a German Jewish industrialist whose extensive art collection was forcibly auctioned by the Nazis before his murder at the Auschwitz death camp.