Sachi Devari could not contain her enthusiasm as she prepared to cast her ballot. "I'm very excited, this is my first time voting," stated the 18-year-old, who arrived at the polling station accompanied by her parents, Gurudatt and Savitha, to participate in the largest democratic process in the world: the elections for the Indian Parliament.

The entire family congregated in a colorfully decorated corridor adorned with children's artwork and informational leaflets at one of the educational institutions in Panjim, the capital of the western state of Goa. Gurudatt, a businessman in the automotive sector, elucidated the family's motivation. "Economic growth is what drove us here. Our economy is strengthening, infrastructure is developing, and I'm extremely optimistic about the future trajectory."

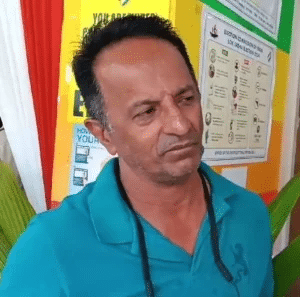

However, not all voters shared this outlook. "True, the economy is expanding, but at what cost?" pondered Sahid Beg, 54, a tour guide standing in the queue ahead of the Devari family. "Corruption is rampant in India," he expounded. "I have faith in the system here in Goa, but not at the central government level. Moreover, look around: in Goa we coexist harmoniously across religious lines – Hindus, Muslims, Catholics. But religion is being injected more and more into Indian politics. Religion poses a major impediment. If this trend reverses and corruption is addressed, India will indeed be number one."

However, not all voters shared this outlook. "True, the economy is expanding, but at what cost?" pondered Sahid Beg, 54, a tour guide standing in the queue ahead of the Devari family. "Corruption is rampant in India," he expounded. "I have faith in the system here in Goa, but not at the central government level. Moreover, look around: in Goa we coexist harmoniously across religious lines – Hindus, Muslims, Catholics. But religion is being injected more and more into Indian politics. Religion poses a major impediment. If this trend reverses and corruption is addressed, India will indeed be number one."

Only time will determine if India ascends to that summit, but in conducting these parliamentary elections, it reigns supreme. This distinction stems not merely from the nation's vast geography, diversity, or the sheer size of its electorate, comprising 970 million eligible voters. Even the 15 million personnel marshaled to operate this gargantuan logistical exercise pales in comparison to the overall colossal scale of conducting the Indian general elections. It appears the authorities in New Delhi are determined to facilitate a record-breaking voter turnout.

For India, the task transcends mere transportation. Whereas in Israel one can vote with just an identification card, India accepts 11 different document types at polling stations, including disability certificates and passports. To curb fraudulent voting, citizens are urged to obtain voter ID cards that confer additional benefits. Voters have access to various apps, such as those that provide candidate criminal record data, if applicable, or help in swiftly reporting electoral violations like intimidation, bribery, or campaigning within 200 meters of polling sites.

Supplementing these are voter education initiatives like SWEEP, aimed at increasing participation and bridging the gender divide in turnout. Moreover, upon announcing the elections, a voluntary code of conduct outlining campaign period restrictions, such as prohibiting electoral promises, takes effect.

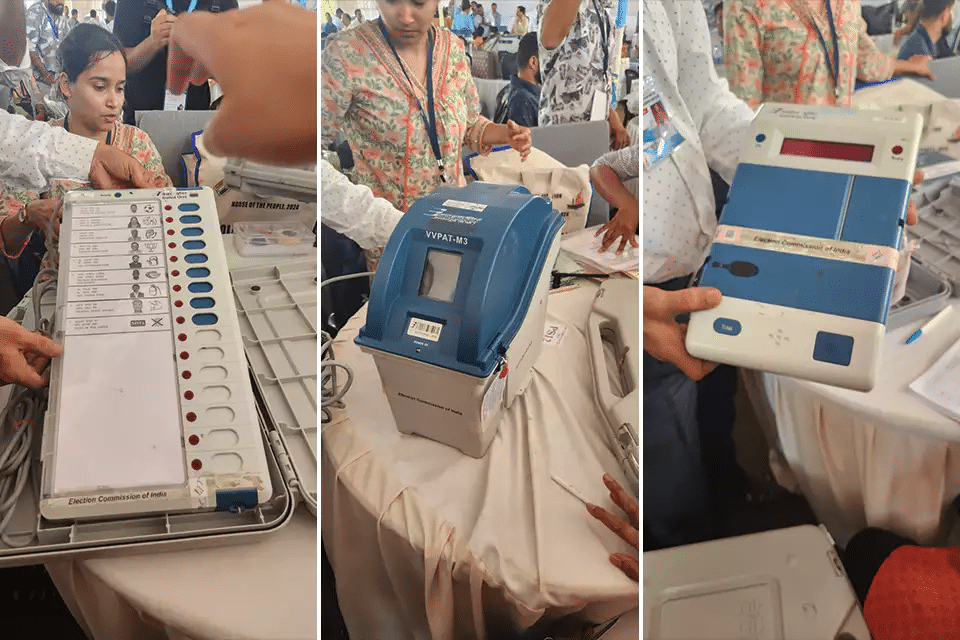

Yet India's elections are perhaps most emblematic of the bridging between innovative and traditional practices – such as indelible ink marking on voters' fingers to prevent multiple voting. The ink's proprietary formula is a closely guarded secret, with only the central election body permitted to procure it. Central to the process is the Electronic Voting Machine (EVM) – an Indian innovation deployed since 1982 and iteratively upgraded with Supreme Court approvals.

The EVM's inception addressed the logistical challenges of printing and transporting voluminous paper ballots while minimizing counting delays, errors, and manipulation risks. According to election officials, the EVM is resilient against hacking since it lacks external connectivity while providing ease of use by allowing voters to simply select their candidate's assigned symbol segregated by party and constituency.

"I would still prefer manual counting," remarked Ignatius Viegas, a Panjim pensioner who voted alongside his wife Joy. "We don't know what transpires inside these machines." Conversely, local accountant Sawari Muthu expressed confidence, stating "I place immense trust in this system. It's the best in the world, tailored for India's magnitude and population numbers requiring oversight."

I encountered the couple at Goa's pioneering green polling station utilizing eco-friendly materials – one of the state election commission's initiatives to enhance the voting experience and foster engagement. At some sites, voters could even participate in tree plantation drives along roadsides. "The green concept is excellent," affirmed Viegas. "The natural jungle is receding while the concrete jungle encroaches; we must restore balance." Further socially-conscious innovations included disabled-friendly and all-women-run pink polling stations to promote inclusion and empowerment.

I encountered the couple at Goa's pioneering green polling station utilizing eco-friendly materials – one of the state election commission's initiatives to enhance the voting experience and foster engagement. At some sites, voters could even participate in tree plantation drives along roadsides. "The green concept is excellent," affirmed Viegas. "The natural jungle is receding while the concrete jungle encroaches; we must restore balance." Further socially-conscious innovations included disabled-friendly and all-women-run pink polling stations to promote inclusion and empowerment.

"Since independence, India has been a democracy, and we intend to preserve it as such," asserted Rosalina Pereira, 70, who traveled from Mumbai to exercise her franchise in her registered state of Goa. "I take pride in my nation, and reject any deviation from its secular principles and our freedoms," stated the Catholic citizen, addressing concerns over the Modi government's perceived promotion of Hindu nationalist narratives. "My Indian identity transcends religion, and our Constitution urges unity across faiths in allegiance to this land."

"Since independence, India has been a democracy, and we intend to preserve it as such," asserted Rosalina Pereira, 70, who traveled from Mumbai to exercise her franchise in her registered state of Goa. "I take pride in my nation, and reject any deviation from its secular principles and our freedoms," stated the Catholic citizen, addressing concerns over the Modi government's perceived promotion of Hindu nationalist narratives. "My Indian identity transcends religion, and our Constitution urges unity across faiths in allegiance to this land."

Having conducted 17 general elections since 1952, with all outcomes accepted by contestants, India's democratic traditions are firmly entrenched. This year, the central election commission in New Delhi has accorded heightened significance to the polls. "Democratic elections are occurring in over 70 nations this year," the commission's chairman, Rajiv Kumar, said. "India's successful conduct will be a litmus test for the remainder."