The exact distance between the Lebanese border and the Druze village of Hurfeish is a matter of dispute, and its approximately 7,000 residents find themselves directly in the line of fire – refusing to evacuate, yet wishing for some form of compensation for their lost livelihoods and their role in safeguarding the Galilee region in the face of the enemy forces.

At first glance, it seems implausible that the village is situated less than three kilometers from the Lebanese border. The streets are teeming with activity, cars emit their honking calls, and life appears to be proceeding as usual. The majority of nearby settlements have been evacuated, yet the residents of Hurfeish have remained in their homes. From an elevated vantage, the village bears the semblance of a tortoise: to the south of the carapace is the busy Highway 89, with homes built on either side of this protective carapace. Many residences are oriented northward, facing Lebanon.

Along the main street, I try to attain a sense of the locals. At the establishment Al-Walid, a restaurant whose signage promises authentic Druze cuisine, it is disheartening to witness the tables standing nearly bereft of visitors. Every once in a while, someone might enter to order the signature Druze pita or stuffed grape leaves. "It's not usually like this," the owner of the restaurant, Kaukab, says as she chops a fine salad. "On Shabbat and Friday, the place is full of customers. We arrange tables outdoors to accommodate them."

As I await my order, I engage in conversation with her nephews, Wasim and Waleed Fares, both aged 23. They tell me about their former classmate, Sgt. 1st Class Jawad Amer, who was killed in an encounter with Hezbollah terrorists who had infiltrated Israel from Lebanon. The squares of the village are adorned with his images and those of other fallen soldiers from the neighboring villages. Israeli flags, along with those of the Druze community, can be seen everywhere, underscoring the narrative of this village: a 400-year-old Druze settlement that has never been evacuated, and it appears as though no force can subdue its resilience.

"The entire regional economy is predicated upon the structural configuration of the village," Waleed says. "A major highway goes through here, with a constant flow of traffic. Muslims, Christians, Jews – all travel through this route. Businesses here are based on the travelers who pause during their journey to make purchases, and now, that stream of traffic has, quite evidently, been disrupted. As such, we have grown accustomed to seeing [IDF] tanks everywhere, hearing gunfire at night, and the sounds of interceptions [of missiles]."

Q: And you haven't thought to evacuate?

"Our village has a quasi-religious committee," Wasim explained. "They, together with the [local] council, prefer that any individual capable of defending the village remain. Should an evacuation happen, it would just be the elderly, women, and children. During the 2006 Lebanon War, the situation was even more dire here. Missiles were raining upon us, yet still, no one left."

The family's business is but one of many that has been struggling due to the war. Yet, numerous businesses have continued functioning, hoping someone would stop by. "We are doing relatively well," Waleed says. "We own the land here, and are not burdened with rental fees, so we somehow survive."

Despite the proximity to the border, an aura of security pervades the village. Every few minutes, a jeep with the civilian security team passes by. The Druze constitute approximately 1.5% of Israel's total population, around 150,000 residents. According to data, about 83% of their sons enlist in the IDF, accounting for roughly 5% of soldiers. Their involvement in the security forces remains high even after completing their service: 20% of Israel Prison Service officers hail from this community, as do approximately 6.5% of Israel Police officers.

"We are a military people," Wasim says. "We do the compulsory service, yet with a genuine desire for enlistment. Nevertheless, we sometimes perceive ourselves as second-class citizens. We still serve in the army and do reserve duty willingly, and we serve the state when needed, without even being asked. At the same time, we anticipate a degree of recognition from the state, even after the war."

The community will soon commemorate the Druze holiday of Ziyarat al-Nabi Shu'ayb: The Druze regard themselves as descendants of Moses' father-in-law, Jethro, and throughout history, they have endured difficulties stemming from their faith. "There are Druze communities even in South America," Waleed says, "and everywhere, they have consistently been persecuted for adhering to a distinct religion."

Their worldview, Wasima and Waleed explain, is that the Druze will never possess an independent state: they have perpetually advocated for integration. Everywhere, they've toed the line with the regime to allow them to practice their customs. However, at times, it appears that this perspective has proved counterproductive, rendering them a population susceptible to exploitation or disregard.

Protective layer

In the vicinity of the local council building, I meet Abdullah Khairaldin, the outgoing council head. Seventy-three years old and a father of six, he agrees to give me a brief tour of the area. "We are on the front line," he says as we walk to a vantage point on Mount Adir. "This front is subjected to shelling day and night, yet somehow, we have not evacuated. We have had numerous contentious discussions about this with the Home Front Command. In short, each side perceives the border differently. They determined that residents of villages within two kilometers [1.2 miles] of the border should be evacuated, so we conducted an aerial measurement from the outermost line of houses in the village, which yielded a distance of 2.3 kilometers. However, state measures are according to the international border, and by that reckoning, they say that we are four kilometers from the border. As such, we find ourselves outside the evacuation area."

Most denizens of Hurfeish, Khairaldin explained, lack the financial means to independently finance an evacuation. Approximately 7,000 residents remain in danger. The majority rely on an economy centered around bed-and-breakfasts, small businesses, and a little bit of agriculture. Most have almost stopped working.

Even our photographer wondered whether it would be safe to go to the lookout point, and when we arrived I understood why he was hesitant. The path to our destination is laid with rocket debris. Some of the traffic signs on the way have been destroyed. This location is under fire from all directions. From the lookout, one can discern Lebanese villages including Maroun El Ras, Bint Jbeil, and Ayta ash Shab. "Observe the distance from here," Khairaldin tells us, "and you will see how much we are in the line of fire. Down there is the Biranit camp, and the soldiers stationed there are under constant bombardment. There is also a base on Mount Meron, and they too are being targeted. Just a few days ago, there was a siren here. Since the outbreak of the war, there have been no direct hits in Hurfeish, but that is solely due to our luck and the topographic structure – this mountain serves as a protective layer between Lebanon and our village. However, it's not like it's an impregnable defense that cannot be circumvented."

Not all the homes in the village have bomb shelters, Khairaldin remarked with concern. "We've opened a few public shelters, but not everyone can reach them in time. People stay in their unprotected homes even when sirens blare. Whenever I hear explosions, I go up to the third floor of my home and check where the missile landed."

According to Khairaldin, there's also concern about a ground invasion. Hurfeish stretches over a wide area without a fence, and defending it requires the residents to have quite a few patrol forces.

When asked whether he felt his village was abandoned, Khairaldin admitted he did.

"I feel it. Not just because of the [authorities'] decision not to evacuate, but a general feeling that accompanies us regarding the lack of budgets and project funding. Our situation is difficult. To operate a soccer field, I have to deal with so many difficulties, and it's frustrating to think that's how it is. Our enlistment rates are among the highest in the country. There's an active or reserve soldier in almost every household. If a full-scale war breaks out here, we'll be in the line of fire. And if my residents despair from living here, we'll lose the north. A lot of people who come here call us brothers in arms, but in the end, I feel like we've been left to our own devices."

On the winding road down, I noticed abandoned agricultural plots. The produce has long dried up. The farmers from the village are simply afraid to come and tend to it. Here is the rest of the translation:

In the center of the village, I met Amir Sharaf, the commander of the civilian security team, and tried to clarify with him how to defend such a wide village. "Hurfeish is not a regular village in terms of defense," he confirmed. "We're not fenced in, and the houses of the village are spread out. This creates a rather difficult challenge. It obviously requires a larger force here, obviously more vehicles. We get some things from the council, and some at our own private expense. Our cars, for example, are donated by civilians. This is their 'reserve service.'"

Sharaf shared the frustration that the heavy responsibility falls solely on their shoulders. "No one helps us with defense or otherwise. In my opinion, the state should thank us for not evacuating. We're kind of a border guard, and that also saved them millions. The village opened its gates to all the units. Business owners who relied on catering and food have gone bankrupt, but they still insisted on feeding the soldiers here."

According to Sharaf, the Druze culture is about not leaving. "If something exceptional happens, maybe the women and children will evacuate, but the men will stay. Even in terms of preparedness for difficult times, a Druze home is different from a Jewish home. Every Druze home has a pantry and survival equipment and food for long periods. We didn't need to wait for instructions, it's in our culture."

"What resilience?"

In my conversations with the people of the village, I mostly encountered cautious optimism until I met the incoming council chairman, Anwar Amr. In Hurfeish, there are several clans and each time a different one manages to have a council head elected. Anwar is relatively young compared to his predecessors, and it's hard to find him with free time. He's energetic, moving from meeting to meeting almost non-stop, but I managed to chat with him after a long tour of the schools.

"I heard from the teachers about the situation," he told me. "I don't have any non-formal education, no sports activities, no courts, no halls. I don't have anything I can do with the population. They've neglected the north for decades, didn't pay attention to us, and now we don't even know what to do anymore. If terrorists infiltrate the country, in three minutes they're at my place."

Q: So why exactly don't they evacuate you?

"There's a government decision on evacuation, but no actual order to evacuate. That means for now we're staying. All night we hear interceptions and air activity. The mental state of the people is very difficult, in terms of personal resilience. There's a lot of mental pressure on the children, families, adults. If we leave our home, no one will be left on the northern border."

According to Sharaf, his constituents take pride in their resilience, but he fears they might not be seeig reality clearly.

"What resilience?" he fumed. "There are people suffering, children under tremendous mental pressure in schools, they can't concentrate and learn. There are elderly people living in the old part of the village, they don't have shelters. There are houses here that aren't fortified at all. We've asked the Home Front Command to budget us money to build shelters, for everyone to do independent construction, and we haven't seen anything so far."

"Some 1,300 soldiers have been staying here in the last two months. Day after day they sat here. They entered the schools, took all our public buildings, we embraced them with food, drinks, lodging, everything. They know that's how we are, and today we're in a very difficult situation, the government needs to take care of us in the north. Take care of those who haven't been evacuated."

Q: Do the residents want to evacuate at all?

"There are people who want to evacuate and there are people who will never evacuate. But the prevailing opinion is that we need routine. The businesses here aren't operating, there's no tourism, people are under financial pressure and they're coming to me. There are people who were left with debts from this war."

Amr was careful not to play the discrimination card. "The treatment of Jewish villages is similar," he said. "but in my estimation, it's worse with us. There, maybe they pay them some attention, but to me, they're not paying any attention at all. They don't care."

The unknown

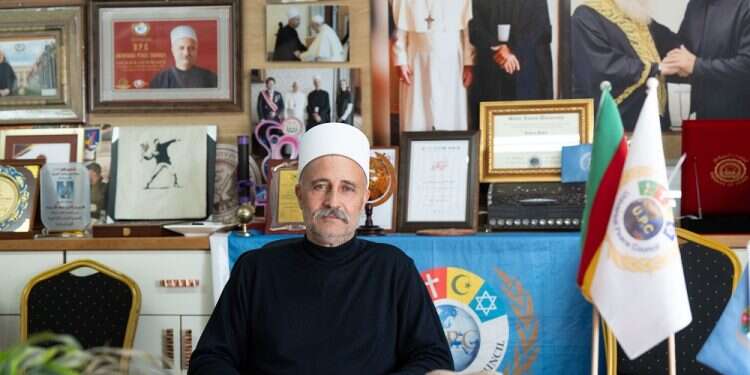

Sheikh Kasem Bader is a sophisticated and pleasant Druze leader. He welcomed me into a room with a table laden with local Druze sweets. Since 2016, he has been the president of the Universal Peace Council – an organization he had founded nine years earlier in Canada, with the aim of "bridging religions and people," he explained in a slow, confident voice. "This organization is waging an ideological battle against those who spread hatred. I think most wars in the world are the product of hate-mongers who come in the name of religion and misinterpret it. Our organization focuses on youth because I believe the only way to change reality is to raise a new generation."

One can learn a lot about the Druze community from Bader's interpretation of reality.

"This land is sacred," he said. "It was meant to be the safest place for us. How did it become the most cruel place in the world? These are questions I ask myself, and they've become more acute since Oct. 7. A month and a half ago, I met with the Pope. I was impressed by how honest he is. We must not forget that there are nearly a thousand Christians in the Gaza Strip, and he is concerned about their fate. We both oppose innocent people paying the price."

Q: How do you continue to promote peace when you're under attack?

"The Druze do not have an independent state. The Druze in Syria are paying the price of Syrian politics, the Druze in Lebanon are the same. The fate of the Druze is that they will always have to contend with the reality they find themselves in. Even on the ideological level, we are not afraid of death. I will leave this temporary mission at the time and place that depend on the Creator of the Universe. Death is a station in life that we all must reach, and therefore people here will never leave. This connects to our culture and belief that death is out of our control and is predetermined in any case."

How do you help people here who don't have money to live?

"There are welfare mechanisms here. The villages in the area also support each other. The situation is not simple. The people of Hurfeish have not received compensation from the state, and some of them have fallen into economic distress. But this place has existed for 400 years, we've been through everything here. The village consists of several clans that know how to support themselves."

Q: How do you try to influence the situation since the outbreak of the war?

"I've met with the families of the hostages. I also have connections in Gaza with some of the leaders. They too are suffering. They're not happy with everything that happened. From their perspective, Hamas is a group of people who simply came and ruined the area."

Said Sharaf, his son-in-law who serves in the civilian security team, joined the conversation toward the end. "On Oct. 7, we were called up for reserve duty," he recounted. "I only got a weapon. There were no uniforms, no ammunition, nothing. I had to scrounge for shoes. But we're people who make do – everyone brought something for the other. People in the village who had served in elite units came to train us on their own time. That's how it is with us. The Druze are not afraid. A Jewish friend told me that if terrorists were to enter a Druze village, they wouldn't have come out alive. There's no such thing as kidnapping and escaping, they would have died on the spot. In Syria, there was a case where ISIS entered Druze villages, they managed to murder two hundred people unfortunately, but one of them said he didn't know how people gathered within an hour and drove them crazy, killed them one by one."

I slept in one of the empty guest units in the village. I didn't know what to expect, but the night was surprisingly quieter than expected. No interceptions, no sirens.

In the morning, I woke up to a breathtaking view in deep shades of green. I spent a full day within spitting distance of the border and didn't feel scared for even a moment. Perhaps because the IDF had recently withdrawn from Khan Younis and an unofficial ceasefire of several days had emerged in the north, but perhaps it's the atmosphere that the residents of the village impart on any visitor. It seems the Druze simply know how to better cope with the unknown, and something about that optimistic feeling rubs off on their guests as well.