1.

"We were slaves to Pharoah in Egypt and the Lord took us out with a mighty arm and an outstretched arm" (Passover Hagada). Slavery is first and foremost a state of mind. We can be free to act as we please, but our consciousness will still be that of a slave. The slave is dependent on the gaze of his master who affirms his existence and confers legitimacy to his actions. The master can take the form of peer pressure or a global zeitgeist. When Moses is sent to free his people, he has to first awaken their consciousness of freedom, to persuade them that their situation is not natural and that once upon a time their ancestors were free men. There are situations where we require divine intervention to shake us up and pull us out with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm from our mental and psychological mud.

Moses too underwent a similar process. He grew up in the home of the leader of a global empire and could perhaps have inherited him. Was he sure of his identity? "And it came to pass in those days, when Moses was grown, that he went out unto his brethren" (Exodus 2:11) – on the face of it, he went out to his Hebrew brothers as Nachmanides, the Ramban, wrote in the 13th century: "This indicates that they told him he was a Jew, and he desired to see them because they were his brethren." On the other hand, in the 12th century, Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra wrote that this referred to "his Egyptian brothers for he was in the King's palace." Both interpretations are correct. It is possible that at that moment in time, Moses was unsure of his identity and had yet to decide who he would tie his fate to. And only when he sees a Frenchman beating one of his brothers, a Hebrew by the name of Alfred Dreyfus that he sees clearly and understands with whom his fate lies… "He saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, one of his kinsmen. He turned this way and that and, seeing no one about, he struck down the Egyptian and hid him in the sand." From Moses' perspective, this is a rebellion against Pharoah, his adopted father. After this act, there is no way back. In psychoanalytical terms, this is "patricide" and constitutes the beginning of emancipation and the beginning of the path to an independent consciousness.

It is a time of war; our people are fighting for their existence. The nature of this struggle differs from our previous history – we no longer hide or flee from the enemy that harasses us; we fight back. At this time, the Jews of the world must rise above their Diaspora consciousness and mobilize for the struggle, wherever they may be. Even if they have to face hostility and even if they have to pay a price, they must choose their people. Thus, we will be able to go out of Egypt, out of the narrow straits of an enslaved national consciousness.

2.

"And if the Holy One, blessed be He, had not taken our ancestors from Egypt, behold we and our children and our children's children would [all] be enslaved to Pharaoh in Egypt" (Passover Hagada). This week, I spoke with a woman who made Aliya from a South American country and built a family here in Israel. "I experienced antisemitism, people threw stones at me because I am Jewish," she said. I said to hear that when her family recites the Passover Hagadah, she should speak of her personal exodus from Egypt. For her, it is not as if she went out of Egypt, she physically left Egypt and crossed deserts and oceans to return home to Zion.

Our sages relate that the ancient Hebrews in Egypt had scrolls that told the story of their ancestor Abraham who left his homeland and his father's house in Ur of the Chaldees to go to a new motherland. These scrolls also told the story of the third of our patriarchs, Jacob, who for fear of his brother Esau, went into exile in Haran to stay with his uncle Laban, and returned only twenty years later with his extended family and now in possession of great property. Just before he enters the Promised Land, Jacob finds himself on his own and encounters an angel who wrestles with him and tries to destroy him. Jacob does not run or hide; he fights back until he forces his enemy to admit defeat and to bless him. Ahah, say the readers of that story, it is at this point that we received the name Israel, for "you have wrestled with God and with men, and you have won!" (Genesis 32:29). We have great strengths that await to be released when we emancipate ourselves from slavery.

And so, the Hebrews in Egypt read that Haggadah and took consolation from the poverty of slavery. From generation to generation, they passed on Joseph's promise made just before his death: "I am about to die. God will surely take notice of you (in Hebrew: 'pakod yifkod') and bring you up from this land to the land promised on oath to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob" (Genesis 50:24). Jospeh repeated this coded message when he said to his brothers: "When God has taken notice of you ('pakod yifkod'), you shall carry up my bones from here." One day, the Savior will come to take you back to your land. He will use this code (I have taken notice of you; "pakod pakadeti") to open your consciousness and break open the gates of exile. I remember you; it is time to go free.

This memory that parents passed on to their children retained the Hebrew national core deep in our consciousness so that it did not disappear, so that our ancient hope - to be a free people in our ancestors' land which we did not know but dreamed about in our time of poverty - would not disappear.

3.

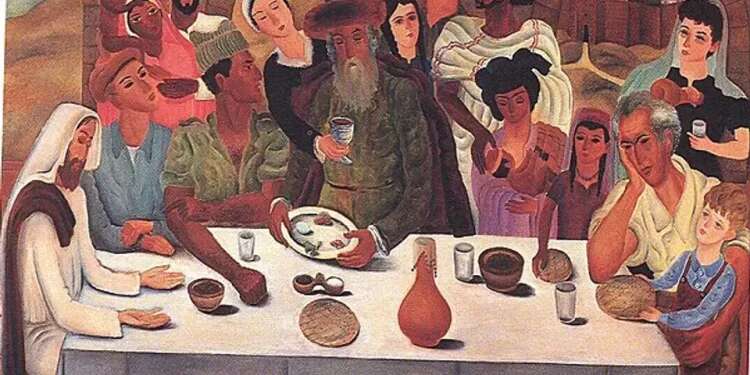

Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Yehoshua and Rabbi Elazar ben Azaria and Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Tarfon reclined [for the seder] in Bnei Brak. And they told of the exodus from Egypt all that night; until their students came in and said, "Masters – the time for saying the Shema of the morning has come" (Passover Hagada).

Today, the Passover Haggadah preserves a small part of that initial scroll which had been told about the exodus of our Patriarchs, while most of it deals with the exodus of our people from Egypt. Between the lines, one can read the Sages' view of the last exile under the rule of the Roman Empire which destroyed Jerusalem and suppressed our independence. The Haggadah is therefore a generic document that motivates each generation to reflect on its situation and leave the Egypt of its time.

In antiquity, Bnei Brak was located near today's Messubim junction, hence its name (messubim means "they recline"). The sages of the generation after the destruction of the Temple gathered at the home of Rabbi Akiva, a disciple of Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Yehoshua, and recounted the exodus from Egypt throughout the long night of their exile. They dealt with the exodus of their generation until came the time to recite the Shema at dawn, the dawn of redemption.

This meeting took place at the home of Rabbi Akiva, the spiritual leader of the Bar Kokhba revolt, just before the outbreak of the revolt in 132 CEO. The revolt hoped to free us from Rome's rule, resurrect the ruins of Jerusalem, and restore the Temple. Unfortunately, the rebellion did not succeed, and we paid a terrible price. But our brothers' sacrifice was not in vain. They carved out the stones from which we succeeded in establishing the third Kingdom of Israel. That great spirit burned secretly during the long night of our last exile, and at the moment of truth ignited the fire of rebellion in the fields of Israel to rise up and leave the Egypt of our time.

We continue to renew this ancient story. We, in our time, have been privileged to write a new chapter: the establishment of the State of Israel. We too must tell of this exodus. Precisely now, when our brothers and sisters are in trouble and captivity and our joy is mixed with great sadness, it is important to tell this great story so as not to get confused in our way, to remember from whence we came and where we are headed, even if we have to pay a heavy price along that way. The Haggadah that repeats the story of cruel enslavement during our times in exile, reminds us of what the terrible alternative is. We understand that it is good to pay a heavy price for our independence.

"And even if we were all sages, all discerning, all elders, all knowledgeable about the Torah, it would [still] be a commandment upon us to tell the story of the exodus from Egypt. And anyone who speaks at length about the exodus from Egypt, behold he is praiseworthy" (Passover Haggada).