Heinz Böhme met Ludwig Jonas all the way back in 1984. Böhme, then a doctor in his 50s, decided to organize all the art brochures and catalogs he had collected during his many trips to conferences and lectures around the world. As he was throwing out a heap he deemed unimportant, a red catalog caught his eye.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

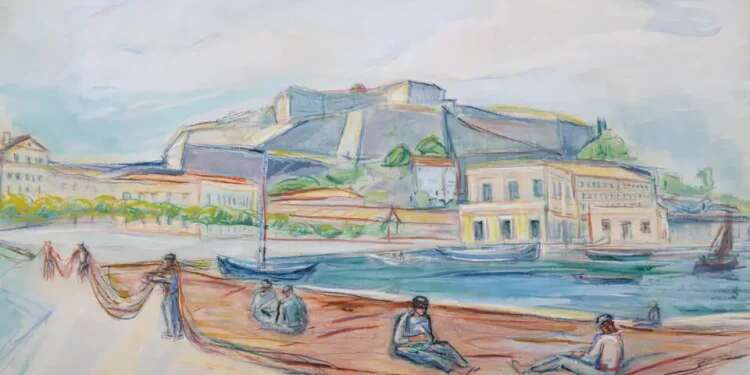

Böhme pulled it out of the bin. On the cover of the brochure the name "Jonas'' appeared in white, that of a fairly unknown painter at the time, and on the pages of the catalog, pictures of an exhibition held in Berlin under the auspices of the Israeli Embassy in Germany, including photographs of the artist's paintings. The unconventional way how the works were presented piqued Böhme's curiosity and made him wonder who Jonas was.

Jonas' biography revealed that he and Böhme had a few things in common. Böhme was mainly interested in the fact that Jonas - a Jew born in 1887 in Bromberg, which was in East Prussia at the end of the 19th century and is now part of Poland - studied medicine like him, but decided to abandon the promising profession in favor of developing his skills as a painter.

In 1909, Jonas joined the School of Applied Arts in Berlin, studied with some of the greatest German painters of the time, continued his studies in Paris, and after World War I, when he served as a volunteer in field clinics, became one of the most promising impressionists in Germany.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Jonas fled to France. From there he immigrated two years later to pre-state Israel and settled in Jerusalem. He continued to paint and exhibit his works, but died of an illness at the early age of 55, more or less around the time Böhme discovered him and his work.

Due to WWII and the persecution of Jews, Jonas' artistic career was cut short and his name was almost completely erased. After his death, his widow Lottie established an art gallery in their Jerusalem home. She would raffle off Jonas' paintings, to encourage local art enthusiasts to visit. In the 1950s the house was demolished, and the gallery moved to another location.

After discovering Jonas' works, "I started looking for his paintings," Böhme, 91, told Israel Hayom. "To date, I have purchased about a dozen of his works. Jonas painted a great many portraits, and faces have always interested me. Perhaps because of my medical practice." It fascinated me how his art career was cut short, and I asked myself whether other artists met the same fate.

And so, following in the footsteps of Jonas' story, Böhme began a journey of over four decades after the "lost generation" – artists whose professional careers faded in between the two world wars, because they were persecuted by the Nazis for being Jews or were political opponents of the regime.

Böhme began to acquire the works of these artists at auctions as well as from collectors and relatives. After accumulating several hundred works, he decided to establish in his current city of residence, Salzburg, a museum where his private collection will be displayed, the Museum "Art of the Lost Generation," the only of its kind in Europe.

His collection consists of about 600 works. Although established five years ago and located in the heart of Salzburg's old city - not far from Mozart's birthplace - this unique museum is almost unknown outside a small circle of enthusiasts. For example, it only recently hosted a senior official of the Salzburg municipality, who learned of the museum's existence from local TV.

In his almost detective-like research work, Böhme revealed not only the works of the "lost generation," but also their life stories, which often ended in the most tragic way.

One such story is that of Rudolf Levy, who was born in the Prussian city of Stettin (modern-day Poland) in 1875 to a well-established Jewish family. He moved to Berlin, where he first worked as a carpenter before enrolling at the age of 20 at the art academy in Karlsruhe, and later at a private painting school in Munich, where he met, among others, the renowned painter of his generation, Paul Klee. Later, Levy continued his studies at Henri Matisse's studio in Paris.

In WWI, Levy volunteered in the German military and fought in its ranks on French soil. After the war, he established his own painting school in Berlin, but when the Nazis came to power he left the country. Many of his paintings were defined by the Nazis as "degenerate art" and confiscated. Levy came to the United States, but before WWII returned to Europe yet again, and when the war broke out he found himself in Italy unable to leave due to financial reasons.

Despite his friends' warnings, he continued to appear in public, and in 1943, was arrested after being captured in Florence by Gestapo agents posing as art dealers. In January 1944, Levy was transferred to a concentration camp in northern Italy, which was a transit camp to Auschwitz.

Samuel Solomonovich Granovsky, born in 1889 in the city now known as Dnipro in Ukraine, studied painting in Odesa and Munich, and in 1910 settled in Montparnasse, the artists' quarter of Paris at the time. Alongside his work as a painter, he was also a model for other painters and earned a living as a cleaner in a cafe.

Granovsky quickly became known as a talented painter, mainly thanks to his nude paintings, and he was very active in various artist circles in the City of Light. In 1942, he was arrested by the French police as part of the Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup – the most extensive arrest operation of Jews in occupied France – and sent to the Drancy concentration camp, and from there to his death in Auschwitz.

Mommie Schwarz, who was born in 1876 in the Netherlands, also studied painting at the Royal Academy of Arts in Antwerp and was considered a promising abstract painter, when he was arrested with his wife by the Nazis in Amsterdam in 1942 and murdered a few days later in Auschwitz.

And there is also the story of Martha Bernstein, daughter of Julius Bernstein, professor of physiology and rector of Halle University in Germany, and of pianist Sophia Levy.

Born in 1874, Bernstein grew up in Imperial Germany, which did not allow women to study painting in higher education institutions and state academies, but only in private schools, and where a woman choosing a career as a painter was extremely frowned upon.

She first studied at a private school in Munich, and from there she moved to Paris, which embraced female painters from all over Europe, and she also studied at the Matisse Academy. When she returned to Berlin she joined the Secession, an artistic protest movement against institutional art, and was a significant part of the modernist movement in German art.

In 1923, Bernstein married conductor Max Christian Neuhaus, who later became the music editor of the Nazi newspaper Völkischer Beobachter. She was persecuted by the Nazis for being Jewish and a painter and managed to find refuge in Switzerland, where one of her two brothers lived. After the end of the war, she returned to Germany, where she died in 1955.

The case of the painter Alfred Schwarzschild is quite unusual: he was born in 1874 to a wealthy Jewish family from Frankfurt. From a young age, he showed artistic talent, and in adulthood, he was sent to study at the art academies of Karlsruhe and Munich. He began exhibiting regularly even before WWI, after which he became a highly sought-after portrait painter among Munich's elite.

His success was interrupted when the Nazis came to power. To make a living, Schwarzschild switched to painting landscape postcards. Thanks to his great talent, the Nazis allowed him to continue this activity, and also ordered postcards from him, on the condition that he would not sign them. In 1936, Schwarzschild managed to immigrate with his family to Britain. For a while, he was detained on the Isle of Man, but upon his release moved to London, where he died in 1948.

His daughter, Theodora Starker, served as a model for the most popular postcards Schwarzschild created for the Nazis. Today, aged 90, she lives in New Zealand, and has transferred her father's entire artistic estate to the Museum "Art of the Lost Generation."

"The primary goal of the museum is to rediscover the works of these artists and present them to the general public," Böhme said. "The creativity of these artists was broken during the Nazi period, and we are bringing it back to life. But what is important, beyond the exposure of the works, is the exposure of the unknown biographies of the artists – what happened to them, what they experienced, and what their fate was. My intention was not only to bring people to the museum to see these works of art, but to teach them about what happened at that time. Through the works and the stories of life, the past can be explained better, and this is our contribution to the present.

"People ask, 'How can we fight antisemitism?' This is one of the ways. To create interest in history in a different way, and not to retell what is already known. Here we create a different basis for coping: with each painting, we tell the accompanying life story, which is sometimes reflected in the painting as well, and people develop different attention. Locating the works takes a lot of time. It's painstaking. We search all over the world.

"Today we have five art historians working with us. There is a person in the US who sends me emails several times a week, with information about places where you can find works by artists from the lost generation. Some people donate works they have in their possession. Some wish to remain anonymous. In the past, these works could be purchased cheaply. Today, they already say at auctions 'If Böhme is interested in it, there is a reason for it', and the prices are rising.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

"It is important to note that we are not a Jewish museum. Most of the artists were Jews, but there are also communist artists and non-Jewish artists who were persecuted by the Nazis. We do not limit ourselves to Jewish artists, nor do we collect works of the well-known artists of the time. I am interested in what happened to the disciples of famous painters. For example, Max Beckmann. Who knows who his disciples were? They are not shown in museums and experts do not know about them. We have collected 90 works by his students, and we are planning an exhibition of them in the coming months."

Although Böhme himself prefers not to highlight this, he too belongs to the "lost generation." He was born in Leipzig in 1932, a few months before the Nazis came to power in Germany. To this day, he does not speak of his family's story during the Holocaust.

"This collection is also intended to commemorate my family," he said. Böhme also expressed concern for the future of the collection and the museum. "Until now, I have covered all the expenses out of my own pocket. There is no support, not from the Austrian government, not from the state of the province, not from the municipality of Salzburg. This initiative, and the story it conveys, should be passed onto future generations."