In 2004, Prof. David Neiman passed away at his home in Los Angeles at the age of 82. His daughters, Rachel, Rina, and Becky then had to go through all his remaining belongings and papers to empty the house of its contents. During this effort, Rina was amazed to come across the old dresses of her late mother, Shulamith, who passed away in 1975 following a long struggle with cancer. These were Yemenite and Bedouin dresses, in which the mother used to appear in her beloved profession of singing folk songs. Rina decided to photograph the dresses and upload the photos to the internet so that her friends too would be able to gain some impression of the style and fashion of yesteryear. Five years later, she was extremely surprised to get a phone call from a journalist in Wyoming, who told her that she had come across the photos and wanted to prepare an article on the subject.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

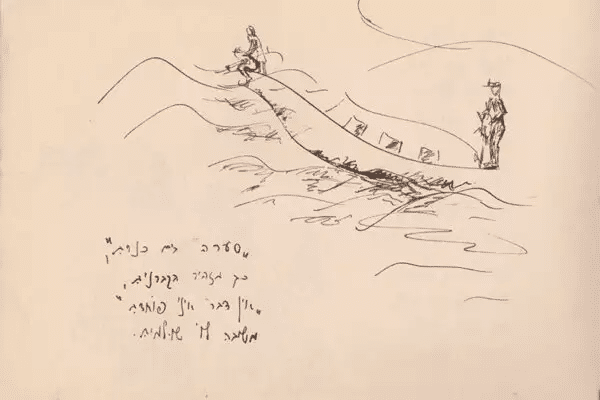

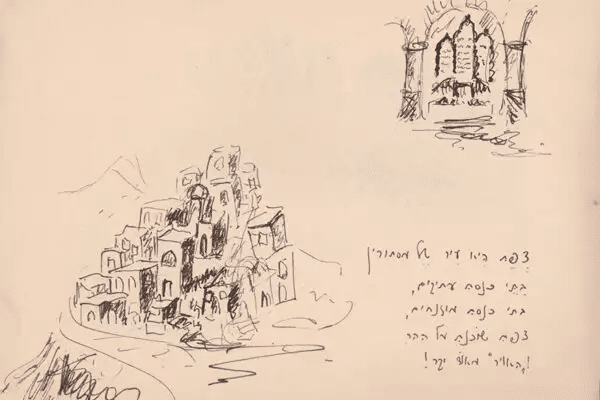

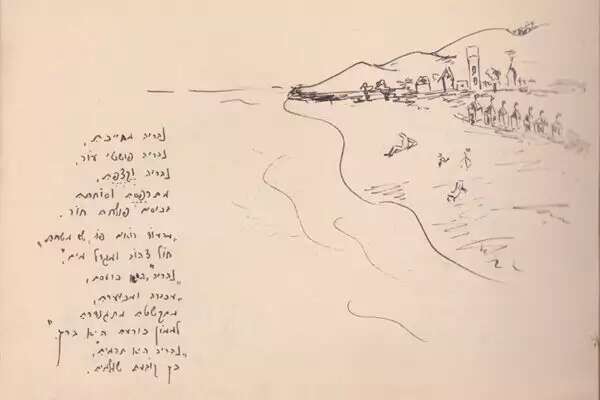

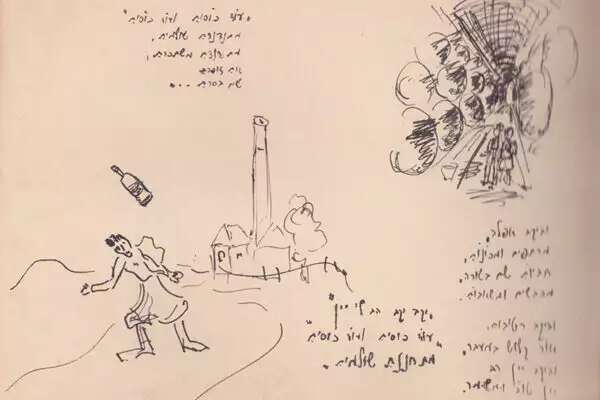

Rina spoke with the journalist, who asked for additional background material on Shulamith, but Rina really didn't have that much to tell her. Her mother died when she was 11 years old, an age when you don't ask too many questions, and her mother, as she recalled, was not the sort of person to share stories from her past. Rina knew that her mother, who during the 1950s worked in the Israeli Consulate in New York, was a very orderly and organized woman, so she began to sift through the boxes of papers that remained. It was here while rummaging through the papers that she came across an old booklet entitled "A Trip to the Galilee" that her uncle, Abraham Dubno, wrote and illustrated in the summer of 1947. It told of a journey of a brother and sister, from Tel Aviv to the north, to take in the scenery of the state that had yet to be established. They bathed in the Sea of Galilee, went up to Safed, passed through Nahariya, and drank at a winery. This was the start of a discovery of a remarkable piece of history.

Rina hardly remembered her mother and clearly never knew her uncle, who was killed during the War of Independence in 1948 at the tender age of 22. "I stood there, amazed and surprised: Who is this woman that I do not recognize?" Rina recounts. "The journalist said, 'I want to write more about your mother, this is a fascinating book.' I replied, 'No, I want to write about my mother, as I know nothing about her story.'"

A few weeks ago, Rina came to Israel straight from her home in Berkeley, California, to meet Rachel, her sister who made aliyah to Israel 40 years ago. The two of them sought to reconstruct at least a part of the long trip that their mother and uncle had embarked on 76 years ago. "When was the last time we went on a trip like that?" Rachel tried to remember. "We met in Los Angeles a year ago, but we really didn't take time out to go traveling."

Rina was more specific. "I came to Israel at the age of 18, I worked at a kindergarten in Ma'alot as part of the Hachshara ("Preparation") year-off scheme I attended, organized by the youth movement to which I belonged," she recounts. "At that time, I wasn't really sure what I wanted to do with my life, but since then I have never been to visit those places."

With Amos Kenan on Ahad Ha'am Street

We set off early in the morning. This time in an air-conditioned sedan and not by bus or hitchhiking as they did back in 1947. Rina (59) pressed her face to the window to take in the views and scenery she had almost managed to forget. For years, she had lived the good life in the USA. She worked for a large agency organizing concerts, she herself managed a club that hosted gigs and in recent years she became more involved in the world of PR.

Rachel (62), her older sister, has gone through numerous different spheres of work during that time. She was a theater lighting designer, worked in journalism, public relations, and marketing, and is currently, among others, in charge of international media at the National Library of Israel. "On the one hand, the experience of losing our mother as young girls tore us apart, but it also drew us closer together," she is convinced. "I came to live in Israel, and Rina moved to California. Becky, our younger sister, lived for many years in New York, but we have always made the effort to remain in contact."

Q: What is it that you didn't know about your mother?

"We really knew nothing. For example, I asked her on several occasions how did our grandmother die? Once, she said that this was due to a heart attack, and on another occasion she mentioned cancer. We knew that we have no grandfather or grandmother, we knew that her brother was killed during the war and that her younger brother, Israel, died of cardiac arrest. But nothing beyond that. There were several strange issues. Once, I asked if we had relatives who perished in the Holocaust, and she replied 'No', but there were some who did die there. I think that she just didn't want to bother us with what was troubling her. When we began to look into her life story, everything we heard came to us as a complete shock."

It emerges that Shulamith, their mother, worked during the 1950s as the secretary of Esther Herlitz, Israel's Consul in New York. It was then, through friends, that she came to know David Neiman, who was an ordained rabbi and an expert in Jewish theology and Bible studies. "He was much more romantic and sensitive than her," Rachel is convinced. "They went out for two years before they decided to get married. On one occasion, they stood on a bridge in New York eating strawberries. She said something like 'I love strawberries', and he asked, 'Do you love me too?'. She replied: 'I am fond of you, but I really love strawberries.'"

The couple finally got married in 1955. Rachel was born in New York and Rina in Boston, to where the family had moved due to work that Abraham, their father, received from one of the universities there. The mother made a living as a guitarist and a singer of Israeli folk songs, but not only that. She was an expert in Spanish flamenco and Portuguese fado dancing. Her hallmark was the brightly colored Yemenite dresses she wore when appearing before an audience, though she was actually of Polish descent.

"My mother was born in Israel in the period when the modern culture was just beginning to develop here," Rina recounts. "It was important for her to be an Israeli icon and her generation gladly adopted everything they could." Rachel adds: "When my mother passed away, we did not inherit from her any gold or pearls, but Yemenite silver jewelry."

The girls remember a fair number of journeys and trips during their childhood. Their father gave several lectures on traditional Jewish music, and their mother would accompany him by singing. "I had an Israeli childhood," Rachel recalls. "The songs that I heard were 'Uga, Uga' or 'Hashafan Hakatan' (the little rabbit). Mother was always keen to keep abreast of developments in Israeli music, and if Arik Einstein, who by the way was a distant relative, released a new record, we would have it. We were constantly dancing to the music of the High Windows, the 1960s pop group featuring Einstein. We owe our love of culture to her. Mother spoke Hebrew to me until the age of four, but then one day I came home from kindergarten and said that I don't want to be any different from the other kids there."

In 1971, the family moved to Rome, where David was the first Jew to teach at the Pontifical Gregorian University in the Vatican. Every year, they would come on a visit to Israel, and in 1973 they were here on their father's sabbatical, and experienced the dark days of the Yom Kippur War in the air raid shelters, along with everybody else.

"After the sabbatical year, my parents spoke about making aliyah and coming to live in Israel," Rachel recalls. "They asked us if we also wanted to come and of course, we gladly said yes, as we had always had a great time in Israel. We joined the local youth movement and we also felt a good sense of belonging at school. However, strangely enough – when I was in the Scouts and we took part in the Sea-to-Sea trek (from the Mediterranean to the Sea of Galilee) – my mother joined as an accompanying parent but did not mention the fact that she had been to all those places during the trip with Abraham, her brother. All I remember is that on the last day, we had to come home early as she didn't feel well. I don't know if this was because of the cancer or the fact that the trip was too emotionally powerful for her."

Shulamith Dubno contracted breast cancer at a time when the research and treatment were at an embryonic stage. She slowly deteriorated and withered away. A friend of the family who visited her in a hospital in Boston told them that she was already in the stage of hallucinations, and on one occasion she looked at the door and shouted "Abraham", apparently looking for her brother.

Shulamith passed away on November 8, 1975, at the age of 47, and was buried at the Giv'at Shaul cemetery in Jerusalem. "Our father asked, 'Do you think that she should be buried in Jerusalem?'", Rachel recalls. "We replied of course, as during the sabbatical year we had lived in Jerusalem, and I had absolutely no idea that most of her family was buried at the Nahalat Yitzhak cemetery in Tel Aviv. Had I known, I would have said that she should be buried alongside her family, but my father did not tell us."

Rachel explains that her decision to come and live in Israel followed her mother's death. At the time she was a member of the Zionist youth movement Young Judea, and many of her classmates came to Israel. In 1984, at the age of 23, she found herself in Tel Aviv, and one year later she had already purchased an apartment on Ahad Ha'am Street. At the time the city wasn't the real estate gold mine that it is today. That specific area was inexpensive and trendy, and it reminded her of Greenwich Village in New York.

"They told me that Amos Kenan had grown up in the building where I bought the apartment. I had no idea that he was Abraham's best friend. It was a family relative who told me of this." Rachel recounts. "When I introduced myself to the residents there, it turned out that Eli, Amos' brother, was still living there. When I told him who I was, he looked at me and said, 'I can't believe it, I can actually trace the very contours of your face.' That was a really weird experience for me. It turned out that my mother's family lived on the adjacent Melchett Street. I didn't even know that this was her local neighborhood, as she never took me to this area or showed me the house where she grew up."

Nurith Gertz, the wife of the late author and artist Amos Kenan, published the book Al Da'at Atzmo (Unrepentant) in 2008, a sort of biography comprising a mixture of truth and fiction, based among others, on interviews she held with Kenan and various figures he knew throughout his life. The first part describes the author's adolescence and mentioned the relations with his friend, Abraham Dubno, Shulamith's brother and the girls' uncle.

"I am reading the book and suddenly it hits me that this is my address," Rachel enthuses. "It was very strange to read the first few pages, as not only do I know the house – but I also know where each room is located. Abraham surely came through this door on at least one occasion."

Dubno is mentioned on several occasions in the book. "This is one of the reasons why Amos likes to visit Dubno," the book states. "There, in the afternoon, the mother serves a helping of hot borscht, full of meat and cabbage, and Shulamith's piano music wafts through from the other room. Occasionally, Dubno's father approaches and asks what happened at school, and in the evening he sits down opposite them and beats both of them at chess, something that Ya'akov Levine, Amos' father, had never done."

"Eli Kenan, Amos' brother, told me of the relations between them, and this is also something that is reflected in the description appearing in the book," Rachel says. "It creates the impression that Amos tells us that Dubno is his best friend, but he doesn't know if he is Dubno's best friend. Based on all of this, I get the feeling that our uncle was at the center of this group of friends, and he was the real leader."

But Rachel also went on to receive something more than allusions. A short time after she met with Eli, Amos Kenan's brother, she was surprised to find in her mailbox a note with the following message: "My name is Elisha Gat and I really need to speak with you about your uncle, Abraham." Gat asked Rachel to meet him at the mythological Cafe Tamar on Sheinkin Street.

Gat was an architect and a typical Tel Aviv bohemian, who in the late 1960s ran in the elections for mayor. For a long time, he led the struggle against the changes in Dizengoff Square and campaigned against the destruction of historical buildings on Rothschild Boulevard. In 1976, he was severely injured in a road accident and was forced to cease working. It was not difficult to find him as he was always sitting at Cafe Tamar.

"I met him there," Rachel recalls, "he had a severe head wound, but as soon as I sat down he said, 'I am about to tell you the story as if it was happening here and now. I am excited, and I might even cry as I speak.' Elisha told me that he and Abraham were friends from the neighborhood and that they had a special whistle they used to assemble all of the gang, then I remembered that Elisha came to visit us while we were living in Jerusalem as a family and that when he came he used the special whistle, and when my mother heard it she knew it was him."

Abraham was two years older than Shulamith. Over the years, Rina and Rachel discovered that the two of them had been very close. They used to go by foot to her concerts in Givatayim, and in the booklet too, right at the end of the trip, when they separate, Abraham writes: "And once again it is au-revoir and so a hot, passionate kiss." "Somebody looked at that line and asked, 'Is that his girlfriend?', and I said: 'No, that's his sister,'" Rachel laughs. "That was another time, another generation."

In the rain on the shore of the Sea of Galilee

We stopped the car on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, at the very spot where Abraham and Shulamith had visited 76 years previously. The lake was almost empty, apart from a few tourists who had decided to brave the rain. "'A storm on the Sea of Galilee', so warns the captain," wrote Dubno in his booklet. "' It doesn't matter, I am not afraid,' replies Shulamith."

"When we stood on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, a boat was sailing on the horizon, just as Abraham sketched in the booklet," Rina says as we returned to the car. "This was a surprise, as in the book when my mother boards the boat, she says, 'I am not afraid of anything.' It is extremely powerful to say something like that."

Q: Was that something in character for her?

Rachel adds: "In the National Library there is a database of historical newspaper items. Not long ago, I said that I have never entered my mother's name for a search, and indeed I found a story from 1960. A journalist who was in New York recounted that he went with his girlfriend, Shulamith Dubno, to the Apollo Theater in Harlem to see a gig, and he describes how the cab driver constantly asked them, 'Are you sure? White people don't go into Harlem.' She said 'Yes' without hesitating."

To this day, the girls are not sure where their mother was born. Their grandfather, Ya'akov, worked as a works manager in the Public Works Department of the British Mandate government, the equivalent of today's Netivei Israel (the former National Roads Company of Israel), and he dealt with road laying. They know that some of their mother's initial years were spent in Nazareth, and she told them that she once fell into a well and an Arab lady helped her get out.

Abraham was a member of a model airplane flying club, he studied at the Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium high school. In the school yearbook, others wrote of him that he would probably become a fighter pilot and bomb the Nazis. Abraham joined the Eretz Israel Aviation Club and became a gliding instructor. On completing his school studies, he went to serve as a guard at Kibbutz Tel Amal (today's Nir David) and Kibbut Mesilot in the Jordan Valley, and he then went on to study architecture at the Technion, and he shared a room with Elisha Gat, his neighborhood friend.

"In our old house, there was a closet and I found small pistol bullets inside." Rachel recounts. "I know that there was a pistol too, but I have never seen it, apparently father must have got rid of it. I think that the gun must have belonged to Abraham."

When the War of Independence broke out, Dubno served in the Carmeli Brigade, he took part in the conquest of Haifa, he was one of the soldiers who took part in the conquest of Acre, he took part in the battles in Jenin, and on July 16, 1948, during an attempt to push the Syrians back from the vicinity of Mishmar HaYarden, he commanded his men to retreat and remained behind to treat a wounded colleague. Dubno was hit by a Syrian tank fire and was killed.

At that time, Ya'akov, Shulamith and Abraham's father, was dying from a terminal illness. Initially, the news was that the soldier was missing and then the terrible news of his death arrived by mail. Elisha Gat, Abraham's friend, told Rachel that he was summoned to identify the body.

"Mother never spoke to us about that period, but over the years we received medals that were sent by the Ministry of Defense, and we couldn't understand what they were for," Rachel explains. "They were apparently given to the bereaved families. Rina also found a letter that Mother wrote to the newspaper in the 1960s, in which she complained that there was insufficient recognition and commemoration of the soldiers killed during that war.

"Safed on the mountain and the dear air"

Five years ago, Rina published a book in the US, Born Under Fire, about her mother's life. A large part of the book is based on in-depth research she conducted, part of it is a story in episodes that she had to complete. When we arrived in Safed, she said: "Though I haven't been here for many years, I believe that I did a good job in describing the place."

The old city of Safed has remained more or less how it was before the establishment of the state. "Safed is a city of mystery," writes Abraham in "A Trip to the Galilee", "Old synagogues, neglected synagogues. Safed lies on the mountain and its 'air' is very dear!"

Within the space of a few days, the Dubno family lost both a father and son, but the mother Rachel wanted her daughter Shulamith to carry on with her life. Thus, when it transpired that the daughter had won a scholarship to study music in the US due to her piano-playing prowess, she had no doubt that Shulamith would be able to start afresh across the ocean. And indeed, Shulamith arrived in New York by ship on January 1, 1950.

"We always thought that she earned a scholarship to study at the prestigious Manhattan School of Music," Rina recounts. "When I carried out the research, I visited the school's archive, and they told me that they were unable to find any record with her name on it. A few months ago, I remembered that I had never checked the immigration records at Ellis Island, as somebody wrote about the Metropolitan Music School, a place that no longer exists. This was a private school in New York managed by an eccentric lady, who was under government scrutiny during the McCarthy period. Mother did in fact study there. My theory is that she told everybody that she was studying in Manhattan, as the Israeli Consulate might not have been too keen to have any connection with that lady."

In 1951, Rachel, Shulamith's mother, arrived for a visit to the US, where she died. The girls knew for years that her death was caused by some medical condition, but Shoshana, the widow of Israel, Shulamith, and Abraham's younger brother, told the true story.

"It was she who discovered that grandma was killed in a motor accident," Rachel explains. "I was shocked. It turns out that in the same accident, mother broke her arm, stopped playing the piano, and went from studying music to economics. I remember that I had a schoolteacher who slipped on ice and broke his hand. When I told mother, she said: 'I too once slipped on ice and broke my hand.'"

Rina found a mention of the accident in the Oneonta Star, which is published in Upstate New York. In her letter dated October 3, 1951, it emerges that this was a whole group, some of whom came from the Israeli Consulate, who went out at Rosh Hashana for a trip to Niagara Falls in an open-top car. At that time, it was not mandatory to wear a seat belt and the driver fell asleep. Rachel was killed along with another woman.

"While we were on sabbatical leave in Israel in 1973, we were involved in a car accident, also on the Jewish New Year, on the Derech Hebron road in Jerusalem," Rina recounts. "Though my mother was not in the car, we were. My uncle was the driver. Nothing special happened, but still, Mother did not mention the accident she had been involved in. It was father who asked us never to go out driving again on Rosh Hashana."

Rachel is angry at Nahariya

We stopped the car in Nahariya. Abraham Dubno dedicated a considerable volume of words to Israel's northern seaside resort. "Nahariya is smiling, Nahariya and cream...... 'What else can we see here, yellow sand and towering water.' 'Nahariya', she is angry, 'Murky and ugly, it adorns jewelry and dresses up, it is always ready to bow for the money.' 'Nahariya is a scam,' as Shulamith puts it."

"It was apparently a very expensive city," Rachel supposes. "On that page, she might well be irate at Nahariya, but on the very next page, after she has eaten a cremeschnitte, a vanilla slice oozing with cream, she thinks that it is after all a great place to be. The book has provided us with a glimpse into the relationship between brother and sister that we had no idea about. Recently, when I have come to look at old snaps, I often start looking to find my mother in the crowd. For example, a few weeks ago, there was an old photo of a march and I said, 'Maybe that's her there?' I took a screenshot, sent it to Rina, and also showed it to my partner, who is a dab hand at such things. We know so little about that period when it comes to her."

Q: You didn't know her as adult women.

Rachel: "Yes, that is something that genuinely hurts, as at that time we didn't get on. When she passed away, I was an angry young girl. I thought that she didn't understand me. I was fully taken up with school and the youth movement – typical teenage behavior – and it took me a long time to understand that this was okay. A long time ago, a psychologist I went to, said to me by chance: 'Your mother was in the Holocaust,' and I said: 'My mother was not in the Holocaust, she was an Israeli.' Then she said: 'I'm sorry, it's just that you behaved like somebody whose parents went through the Holocaust.'"

In Nahariya the sun peeped out. Instead of cream cakes that Abraham drew, we ate ice cream at the local branch of Golda, and then we went down to the wonderful golden beach. "When we went down to the beach, I think I felt exactly what they felt," says Rina. "Places so different to those they were used to in their daily life. What they did here they wanted to do across the entire globe, to spend time traveling."

The booklet does not state how many days they spent traveling, or where they slept. Everything appears to be so footloose and fancy-free, with no dangers on the way, no threats. A brother and sister, wandering across the Land of Israel, stopping here to eat and there to drink. In the end, they arrive at the winery, which is assumed to be in Zichron Ya'akov, from there we continued to the Carmel Winery, which used to be Carmel Mizrachi.

Loving laughter

"And in the winery there is darkness," writes Abraham. "Cellars and machinery, barrels arranged neatly in a row, presses and pumps. And in the winery, it is damp, faint, subdued light in the passage, and in the winery, there is much wine, good and well-preserved wine. 'Winery, O winery, bring me wine, another glass and yet one more glass,' Shulamith begs. 'Another glass and yet one more glass,' Shulamith totters, she totters and gets drunk."

"He is laughing at her, but does so in an extremely loving manner," Rachel says defensively. "He writes that she got drunk, but I don't really believe that to be the case. This might even be the first time that she drank, as at that time there was no culture of drinking alcohol in Israel."

Rachel and Rina are more experienced wine drinkers. Rina has toured Napa Valley in California on more than one occasion while Rachel knows how to taste and drink wine. They bought a book at the winery store and we raised a toast in memory of the trip taken in 1947. "I remember when we were young, it took us hours to reach Jerusalem by car," says Rachel. "That's the reason why Abraham prepared the booklet, as it was a genuine project."

We returned to Tel Aviv in the evening after a long journey. "A wonderful day," Rina sums up the trip to scenery she had almost forgotten, while Rachel recalls that the day beforehand they had been on a visit to a family relative. "Rivka told us, 'Thanks for doing it.' At least on the family level, it affords legitimacy to the unknown story about a man who was not famous, and they are not famous, and still, the family feels that it has made a tremendous sacrifice for the state."

At the Nahalat Yitzhak cemetery

We had an additional stop to make before saying goodbye – the military cemetery at Nahalat Yitzhak in Tel Aviv, where Abraham Dubno is buried. Rachel is extremely familiar with this location. "For years, I was unaware of the Memorial Day ceremonies, as nobody said anything, and I wasn't that interested in it," she explains. "At the start of the 2000s, a relative invited me to come with him, and for me, this was a real wake-up call, as it suddenly occurred to me that I am part of something much larger than I thought. To attend the ceremony at a cemetery packed with hundreds of people. I remember that somebody from the government came and spoke, and until then I didn't think that Abraham was a part of me. Since then, apart from during the Covid-19 pandemic, I attend the ceremony every year. It is of great importance to me personally. Sometimes, because of my accent, people think that I am an immigrant from the US, but I make sure that people know that my roots are firmly entrenched here in Israel. This is a genuine sense of belonging."

We stood by the grave of a young man who was only 22 when he died. A young man they had never known and who, in fact, until a few years ago, hardly played any part in their lives. "He actually gave us our own selves," Rachel is convinced. "Had he remained alive, then perhaps our mother would never have gone to New York and met our father. That's the whole issue with coincidence in life and how it throws people in completely different directions, those that you could never, ever expect."

Q: It's a very sad story.

"I find it very disconcerting that we know absolutely nothing. Even when we visited the cemetery, we went to our aunt's grave, we looked at the headstone and we asked who the woman called Faige who is inscribed on it is. Nobody told us anything. Our relatives didn't bother to tell us as they thought that our mother had told us, and she didn't tell us as she wanted us to be happy."

Q: What do you think would have become of Abraham?

Rachel: "I think he would have been a pilot or an engineer in the aerospace industry."

On the last page of "A Trip to the Galilee", Dubno says goodbye without knowing it that just one year later this would be his last goodbye. "Au-revoir next year in Italy or the US," he wrote.

"This story is a tragedy for my mother and her family," says Rachel. "I am sure that every time she was in Rome, or she was traveling in New York, she thought of Abraham and said to herself that it was a shame that he was not there to witness it, just as I have friends who are no longer with us, and I say, 'How I wish that I could share my experiences with them.' This is the reason that I brought the little booklet, "A Trip to the Galilee", to the National Library. I said that 'This might not be a diary, but it is definitely a large piece of life.'"

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!