1.

This year, Passover falls just as we find ourselves caught up in a great dispute, with the flames of feud climbing ever higher, and the prophets of doom presaging their apocalyptic visions. Couldn't Passover wait? Couldn't we fight a little longer? The Hebrew calendar grabs us by the hair to extract us from the latest controversy. Up until now, we have been dealing with the here and now. Let us however deal with the eternal issues that have occupied us as a people from the dawn of time. If we answer this call, we will be given a comforting perspective on our present reality and we will understand that even if the present turmoil seems to us to be an existential issue, at the end of the day, it is no more than a fleeting moment in time in the history of our ancient people.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

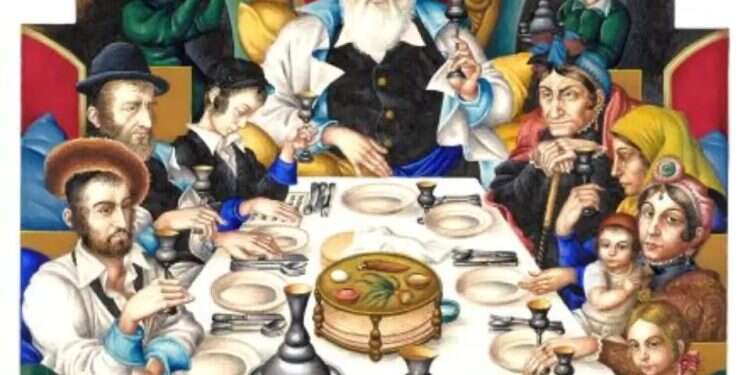

The Israeli discourse tends to flare up, accelerating from zero to a hundred in mere seconds; we also suffer from an inclination to blame the other rather than to deal seriously with their claims. But we are injured and insulted when our claims are disputed, and we immediately launch a counter-offensive. These disputes, these wars of opinions seem to us to be a matter of life and death and our reactions are in accordance. When we read the Haggadah on Passover, we should pay attention not just to the content, but also to the context. Once a year we are given the opportunity to enter the scholarly halls of the Mishnaic sages and discover that they too do not always agree with each other. The Haggadah contains Mishnaic interpretations of biblical verses and while their style is perhaps alien to some of us, we should learn from them that Our Sages of Blessed Memory do not get overly excited about dispute and, in fact, often sanctify it.

2.

Toward the end of the second century CE, following the failure of three revolts in 70 years (the Great Revolt and the destruction of the Temple, 66-70; the Kitos War – – the rebellion of the Diaspora – 115-117; and the Bar Kochba revolt, 132-135), the Jews had to deal not only with the physical destruction of the people and the Land of Israel, and of the communities in the Diaspora, but also with the very real danger of losing their language and culture. For many years, the Jews had kept their biblical exegesis unwritten. There was a halachah or convention that it was forbidden to write anything down, but which required that these interpretations – which were the basis for Jewish law and tradition – be handed down from generation to generation by memorizing them by heart. Unlike the Bible which had been translated into other languages, this was our secret that we did not share with the other nations.

But then, towards the end of the 2nd Century CE, the leader of that generation, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi (Judah the President), who lived in Galilee, decided to write down the ancient traditions, lest they be forgotten. In the words of Maimonides who lived a thousand years later, "…so that the Oral Law would not be forgotten by the Jewish people. Why did Rabbenu Hakadosh (Yehuda HaNasi) make [such an innovation] …Because he saw the students becoming fewer, new difficulties constantly arising, the Roman Empire spreading itself throughout the world and becoming more powerful, and the Jewish people wandering and becoming dispersed to the far ends of the world. [Therefore,] he composed a single text that would be available to everyone so that it could be studied quickly and would not be forgotten." (Maimonides: Introduction to Mishneh Torah).

Our sages learned to do so from a daring interpretation of a passage in Psalms (119:126) "It is time to act for the Lord, for they have violated Your teaching." The pshat (literal meaning) is as follows: It is time to for great deeds in honor of the Lord and to be stricter in adherence of his commandments because there are those who violate the Torah. But Our Sages interpreted this to the contrary: Sometimes there are historical situations where one has to strengthen faith by acts that violate the Torah. In order then that Torah not be forgotten, they violated the halachah that forbade writing down the interpretations. In the words of the Talmud: It is better to uproot a single halachah of the Torah, (i.e. the prohibition of writing down the Oral Torah) and thereby ensure that the Torah is not forgotten from the Jewish people entirely" (Temurah 14b).

3.

Rabbi Yehudah began to compile the oral traditions of the various schools. He edited them and finally put together six volumes or 63 tractates of halachot codifying Jewish law and encompassing the entirety of Jewish life. After the Bible, the Mishnah is our most ancient codex of laws. Besides compiling these traditions in writing, the innovation here was introducing opinions that disputed the various halakhot.

It is hardly standard practice in a book of laws to write: This is the law that forbids doing a particular act, but you should know that there are those who think it is permissible – or vice versa. But for the Jewish people, this is an ancient ethos that goes back thousands of years. Dispute does not threaten us, it enriches and inspires us. The premise is that the truth is an amalgam of several opinions, and if this is the case, then there is truth in the dissenting opinion, and it is wrong to suppress it, even if it is not accepted by the majority. The most important thing is that the truth transpires through elucidation of ideas and working through differences.

4.

Where do the boundaries of legitimate debate end? The boundaries end when a debate is no longer considered a conflict of ideas – even if highly contentious – but becomes an existential battle and a justification for one side to split off from the rest of the public. We must try to understand the claims of the other side and view them with respect – in other words, not to look at their arguments as a caricature, but to delve deep into the roots of the debate and to try to understand the logic and fears of the other side. We don't have to agree, and we can assume that the arguments of the other side will anger us, but if we understand the logic that lies behind them, then we will be able to calm our fears and realize that this is not an existential struggle but a dispute.

We can perhaps find a pointer in this direction from the words of Our Sages who wrote that "Although Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel disagreed on several legal issues related to family matters … Beit Shammai did not refrain from marrying women from Beit Hillel, nor did Beit Hillel refrain from marrying women from Beit Shammai. This serves to teach us that despite their differences, they practiced love and friendship between them, to fulfill that which is stated: 'You shall love truth and peace.'" (Tosefta, Yebamot 1). This is not a renunciation of truth by either side, but an understanding that alongside love of the truth we must seek peace between us, and that these two elements complement each other.

5.

I do not say all this out of naivete. I live among my people and am part of the dispute. But nevertheless, I can say of myself that not once over the past three months have I been enraged when hearing arguments contrary to my position. I have backed the judicial reform, but I never thought that its opponents were an existential threat and certainly not the arguments that they made. As in any dispute, neither side has a monopoly on the truth.

However, the refusal to serve on reserve duty, or the use of symbolic capital and status to gain the upper hand, do not take us forward in any way and do not lessen the flames of dispute, rather they harm the truth. In fact, they do not respect the debate but serve to present one side as illegitimate.

Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi did not include in the Mishnah the opinions of those who withdrew from the public and left it; in other words, those whose arguments were not aimed at building the national body, but at undermining it. We hear the voices of those who say that the people's vote is not legitimate; they have gone beyond the boundaries of the debate over the legal system and wish to oust the government for various reasons. That is their right, but this political battle will not receive the same kind of public support enjoyed by the protest movement.

Now that the storm has passed and the sides are meeting to engage in dialogue, it is important to recognize the pain of the other side. This recognition will pave the way for healing and unification. As Passover approaches, we can make room in our hearts to pass over the bitter feelings. The Haggadah opens with an invitation: "All who are hungry, come and eat; all who are needy come and celebrate Passover." Let us mean it.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!