If you ever visit the Moscow Jewish community, you will most likely meet Svetlana Tumanov. An energetic 65-year-old woman, the last thing you would ever think is that once, Svetlana was a spook.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

"It's the last thing I would have thought of I would do when I was growing up and when I moved to Israel," she said. But "life unfolds in unexpected ways."

Coming from someone else, it might have sounded like a cliché, but given Svetlana's life, these words carry a special significance. There has been no shortage of unexpected turns in her life, the last one of which led her to call a particular apartment in Moscow her home.

"In 2006, I got an unexpected phone call, and the confident voice on the other end asked me to report to the presidential office. When I got there, a concerned official informed me that President Vladimir Putin had ordered him to assign me an apartment."

In order to explain why a kind Muscovite Jewish woman received such a generous gift from the president of Russia himself, let us journey back in time to when Svetlana, back then Yeta, was just a child in a Jewish family in Riga in the 1950s.

Her father, Shmuel Katz, and his brother grew up in independent Latvia before World War II, spoke Hebrew, were educated in Jewish institutions, and engaged in Zionist activities, that is until the Soviet occupation changed their lives: Both were sent to 15 years imprisonment in a gulag, but paradoxically the cruelty of the communist regime and the exile to the camps in Siberia was what saved them from certain death at the hands of the Nazi invaders. Having survived the war, Shmuel got married and had a daughter – Svetlana.

"When I was four, my parents signed me up for an ice skating class and sent me to study English, all the while their intention was to lay an infrastructure for escaping from the USSR," she recalled. "Thanks to sports we could dream of traveling to a competition abroad and defecting, and thanks to English we could plan our future life in the free world. My mother's brother lived in London, having himself defected. After World War II, as an officer in the Red Army, he handled arms shipments from Czechoslovakia to the newly established State of Israel. Then he chose not to return to the USSR and changed his Jewish name, Shimon Dritas, to Simon Diamond, which sounds more familiar to the British ear."

Svetlana was convinced that her uncle did not live a normal life even after the desertion. She thought that he worked in the service of Israel's intelligence organizations, and even visited Moscow several times when it was closed off behind the Iron Curtain. Either way, her family – the Katzs – were determined to leave the "socialist paradise" at almost any cost, and the opportunity to do so suddenly presented itself in early 1971.

"When I was approaching the age of bat mitzvah, my father gave me a book written by the French author André Gide, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature," Svetlana continued. "I remember it had a poem about the Jews, how we will all be home one day, in the land where David was king. This line impacted me to the depths of my soul. My parents were close to a group of Jews who planned to hijack a plane and escape from the USSR, and after the organizers of this operation were arrested by the KGB, I was so shocked that I copied the lines by hand and distributed them to all the Jewish students in my class.

"When I returned home in the evening, I saw a car at the entrance to our building. I opened the door of our apartment and immediately recognized the father of Ira, my classmate, whom I had always helped study. He held a very senior position – deputy director of the authority that was responsible for issuing exit permits from the Soviet Union. He sat there, explained to my parents that I could cause a disaster for them, but ended the conversation with an offer that was impossible to resist: 'Quickly get a request from your relatives in Israel for family reunification, and I will make sure that it is approved.' I think that the mysterious uncle from London also worked behind the scenes, and in any case, the miracle happened – in June 1971 we left the USSR."

With no direct flights to Israel, the Katzs first made their way to Vienna, where they stayed at a Jewish Agency center, and were even visited by David. Miraculously, he arranged visas for the family and they spent the next three months in London.

"In August 1971, we finally left for Israel," Svetlana said. She was greatly impressed by the British capital, and would soon return there.

The integration of a young Riga girl in Israel was not easy. On the one hand, Svetlana enjoyed the enthusiastic welcome and still remembers that "the Hebrew that the soldiers who met us at the airport spoke sounded like music to me." She excelled in her studies, and as a promising athlete was even interviewed by a local newspaper that dubbed her "the queen of ice skating."

"There was no ice in Israel at the time, so I transitioned into gymnastics and skating."

On the other hand, the routine became exhausting. Svetlana would skip out on school to attend demonstrations for the release of Soviet Jews and dreamed of more. In the fall of 1973, after the tragic death of her father, Svetlana moved to London, 16 years old at the time.

"During one of my walks in the city, I came across the Bush House, which housed the BBC World Service. I remembered how when I was a little girl, my father let me listen to the BBC radio broadcasts and I even remembered the name of the famous broadcaster – Anatoly Goldberg. In a burst of Israeli chutzpah, I went inside and asked the guard to see him.

"To my surprise, the guard called for Goldberg, and on the spot, I was accepted to work for him, on the condition that I pass a Russian typing test the next day. I only knew how to type in English, but I had a whole night ahead of me that to learn to type. Thus, at an age when all my peers were still in high school, I started working in the holy of holies of the world press."

In addition to the promising job, Svetlana also enrolled in the Institute of Linguists. As fate would have it, one of her teachers was Gerald Brooke, a British secret agent who was caught in the USSR and even served four years in prison there, until he was released as part of a spy swap deal. Brooke pushed her to specialize in simultaneous interpreting, not knowing that in doing so he was channeling her life to the dangerous world he knew so well.

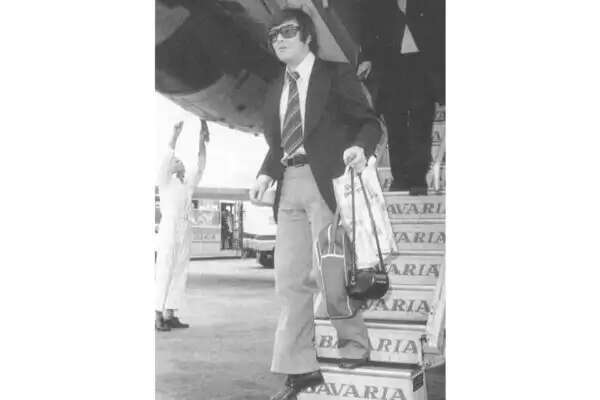

"One day, the BBC reported of the supposed arrival in London of Oleg Tumanov, who was known for his daring defection from a Soviet navy ship while he was in the territorial waters of Egypt, not far from the Libyan border, and was considered a leading opponent of the Soviet regime," Svetlana continued. "After the defection, Tumanov was hired at Radio Liberty, which operated from Munich and served as a central anchor in the propaganda and subversive activities of the US against the USSR. He became the editor-in-chief of the station's broadcasts in Russian and was considered an unimpeachable source by the entire Soviet immigrant community in the West, and in fact by everyone who dreamed of the collapse of the communist regime".

Despite the age and status difference between them, the meeting between the star from Munich and the ambitious girl immediately sparked a love story. Things turned around surprisingly quickly – and only two weeks later the two showed up at the marriage registration office. Another month later, the young couple received permanent residence status in Munich. Very soon, however, things took a dark turn.

"I knew that Oleg often spoke to an American named Alex. Everyone knew that Radio Liberty was run by the CIA, so I assumed that Alex was the representative of the American intelligence agency and that my husband worked for them. One day Oleg held a globe in his hands and asked me to go out on the balcony with him. He handed it to me and asked me to point out the country I thought he worked for. I confidently pointed to North America, then Oleg turned the globe and put his finger on the inscription 'Moscow.'"

Although over 40 years have passed since that day, Svetlana still had a hard time describing what she felt.

"To say that I was shocked would be an understatement," she finally said after a long silence. "My whole world came crashing down. After all, I grew up in a different culture, in an environment that hated the USSR. Even the initial attraction to my husband was born of admiration for his anti-Soviet work, and all of that collapsed at once.

"We slept in different rooms that night, didn't exchange a word, and for a week I passed the time from morning to night in continuous tram rides trying to figure out what I should do now. After a week I gave in. First of all, Oleg planned everything so that I would have nowhere to return: He convinced me to sell my studio apartment in the center of London and to move to Munich in Germany, a city and country where I knew no one. On the other hand, I tried to calm myself and thought that he didn't demand anything from me, and didn't demand that I help him in his espionage activities. I didn't realize that too would eventually come."

Svetlana believed that her husband had no choice but let her into the secret of his affairs already at the initial stage of their relationship. A photo lab was installed in the couple's apartment, where Oleg photographed all the sensitive documents he could get his hands on, and Svetlana would have discovered the strange equipment sooner or later anyway. If that's not enough, there were other spy devices in the apartment – equipment used for encryption, a transmitter and receiver that received the transmissions from Moscow, and more.

"Oleg would often leave Munich for secret trips, which he also found difficult to explain with normal excuses. After all, I might still suspect him of cheating on me and not betraying the country that provided him with refuge, and start sniffing around. Instead, he realized that it was easier to recruit me. At first, he also wanted to be seen as a hero in my eyes – he took the trouble to explain that he really opposes many of the injustices that occur in the Soviet Union and wanted to convince me that his escape from the ship was real. Today I am no longer sure what the truth was."

In the memoir he published in 1993 after he was exposed and fled to the USSR at the end of the Cold War – Tumanov claimed that the defection was staged from the beginning by the KGB and was intended to give him the image of a daring fighter against Communism, to help his future integration into the ranks of the CIA or other Western secret organizations.

According to another version, he was actually recruited by Soviet agents after he settled in Germany following the defection.

Q: Did you never think of exposing your husband for espionage?

"No. I was a young woman in a foreign country, and I was completely dependent on him in every way. Besides, the idea of betraying a family member is against the values of the culture in which I grew up. I didn't feel that he was doing something wrong or terrible. After about a year of marriage, I learned to drive and got a car from Oleg as a gift, but there was also a utilitarian calculation behind this gesture: Oleg's license was revoked after he drove a car and crashed into a pole, and he desperately needed someone to drive him to meetings.

"The first time he suggested that we go on vacation to Austria, and in my innocence, I didn't suspect a thing. We arrived at a picturesque guesthouse in a village that Oleg had chosen, we went down to breakfast, and suddenly two people approached us who for some reason recognized me immediately, even though I had never met them. They started shouting at Oleg, 'How could you get married to her without getting permission from Moscow?', but he responded calmly and explained that because he was not allowed to drive, he needed help. I was told to sit at another table, and they apparently came to some kind of agreement, following which I started helping him."

Q: What were you required to do at this stage?

"To be honest, I was required to be an ordinary wife, one who doesn't ask questions. Two or three times a year I drove Oleg to meetings with the KGB officers who activated him, and that's all.

"Then it went up a notch. It happened when the Americans were looking for a temporary worker for their facility in the town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, where intelligence officers were being trained for future missions in the Soviet Union, and they offered me to teach them, Russian.

"Oleg was shocked and did not want me to accept the offer, but I insisted. The commanders of the facility warned me against any attempt to maintain personal relationships with the students, beyond the educational process. One American captain fell in love with me, yet I was not tempted, but apparently, this short employment was planted in the minds of the KGB people the idea that I can be used fully – and the opportunity for that came quickly."

One day, Oleg's CIA contact showed up at the Tumanovs' apartment and asked to speak specifically with Svetlana.

"I've found your dream job," he told her enthusiastically. "To return to work at the school for training intelligence officers, but in a more senior position as an assistant to the school commander. After all, you were born in Latvia and oppose the communist regime, and as such you will receive the classification with us without a problem."

Svetlana said, "He was sure that I would accept the magical offer with both hands and of course, he did not know what thoughts were running through my head at the time."

The couple found themselves in an impossible situation and were under terrible pressure. If Svetlana refused the generous offer, it would immediately arouse suspicion, because there is no logical way to justify the refusal. If she accepted the offer, she would need to take a polygraph test which may have exposed her.

The Soviet handlers were, on the other hand, overjoyed, as they thought their agent would soon work in the heart of the American intelligence system. They only advised her to drink some milk before the polygraph test, to relax.

"I was so naive that I was convinced that there might be something in the milk that misled the polygraph, and I went for the test without anxiety. Luckily, the questions were worded in Russian and with surprising carelessness, to the point that the main question was worded in a way that allowed me to circumvent it. I passed the test without any problem, and started working in a place that the KGB couldn't have imagined in its wildest dreams."

As an asset whose value was astonishing in the eyes of the KGB, Svetlana was now privileged to have her own handler on behalf of the Soviet secret service. Today, in high sight, she tends to underplay the intensity of the damage she caused to the Americans, but it is doubtful whether intelligence officers would have thought the same at the time.

According to Svetlana, she provided her handlers in the Soviet Union with a wide range of information that was of great interest to them: reports on the location of US Army forces, the exchange of units and their movement, the nature of the armament, and above all a lot of highly detailed personal information about the American agents who were about to be sent on espionage missions in the Soviet Union.

And yet, Svetlana stressed that there was a limit to her willingness to help her husband and that she did everything in her power not to harm the Jewish state. She said that Oleg asked her several times to go to Israel together, but she refused because she suspected that she would be required to do something against the country she loved and appreciated with all her heart.

"Oleg visited Tel Aviv often," she said. "Apparently, he was looking for potential employees for Radio Liberty among the immigrants in Israel. In fact, I assume he had connections with the intelligence agencies in Israel. A few years ago I contacted the Russian intelligence services and asked if they knew about it. I was told that they did, that the KGB realized that Tumanov was a triple or even quadruple agent and that he didn't give the Israelis anything important."

It seems that on other fronts Tumanov did quite a few important things for his operatives in the KGB, only some of which are known. Among other things, it is widely believed that the documents he obtained and passed on to the USSR revealed a "mole" who worked for the US in a circle close to the top brass of the Soviet Communist Party.

In 1974 alone, he provided Moscow with no less than 12 volumes of documents of intelligence interest, and according to other reports, served as a key figure in a KGB operation that fed the West false information for an entire decade. But the intelligence bonanza of the KGB built thanks to the Tumanovs ended abruptly in 1986.

"One morning in February, I reported to work as usual at the American MacGraw Kaserne base, and the commander informed me that my husband had disappeared as if the earth had swallowed him.

"I was asked to accompany the security officers of Radio Liberty to our apartment, to assist them in investigating the disappearance. When I entered the apartment, I immediately realized that he had fled to the Soviet Union. We had an agreed sign in case he had to run away: he had to leave a certain book on the table to warn me. I saw the cover of the book and realized that from now on I was alone against the whole world. I noticed that several items from Oleg's spy equipment were missing from the apartment, and what he was unable to take or destroy I managed to make disappear, without the security personnel who were next to me in the apartment noticing it."

A few days later, Tumanov appeared on the TV screens in the USSR and stunned the world, including his Radio Liberty colleagues, by admitting that he had indeed worked for years in the service of the KGB. The news that a Soviet agent had been operating for many years in the nerve center of an array designed to bring down the USSR greatly embarrassed the CIA.

Tumanov, of course, did not disclose the reason for the hasty escape, which actually symbolized one of the great successes of the Americans. Viktor Gundarev, a colonel in the KGB who knew well about Tumanov's activities and even served for a time as the officer responsible for its operation, defected to the CIA in Athens, and Soviet intelligence rushed to get their agent back from Munich before it was too late.

Svetlana, now the "wife of a Soviet spy," was naturally fired from her job at the US base, but at least managed to fend off for a while the suspicions that she too was involved in espionage. Her Soviet handlers disappeared for a long time, but after about a year she received a phone call from them and was asked to come to Berlin.

"I came to West Berlin expecting that the KGB people I would meet would tell me something about Oleg. Instead, I walked with them from the Friedrichstrasse subway station through a series of corridors, passed through several mysterious doors, and when we got upstairs I saw Soviet cars and gray buildings all around me. Even that didn't open my eyes until we sat down in the restaurant and I tried the meat. I recognized the bland taste I ate as a child and realized – I'm in East Berlin."

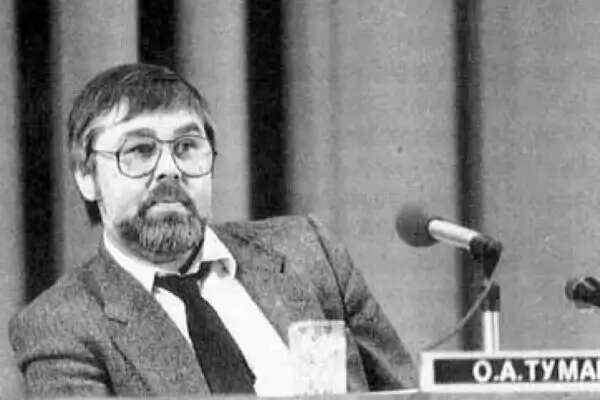

From the restaurant, she was taken directly for questioning at "Karlshorst", the KGB headquarters in the East German capital. An investigator interrogated her for two days about everything that happened at the time of her husband's escape, and the frightened Svetlana – who found out that her husband was being given the status of a hero in Moscow and all the accompanying glory – asked about the possibility of following in his footsteps and returning to the country for which she had served as a dedicated spy. To her astonishment, she was met with laughter from the man sitting across from her.

"What will you do in the Soviet Union during the perestroika era?" he said. "At most, we can arrange a job for you as an English teacher in a remote rural school."

Svetlana was later smuggled to East Berlin two more times, but time after time she was met with a cold shoulder. With no choice, she returned to Munich, and the scenario she feared came true – at the request of the Americans, the German authorities arrested her on suspicion of espionage. However, she was lucky again.

"I sat in a detention center for six months, and then the court acquitted me of the charges within three days. I think it was the Germans' revenge on the Americans, for surveilling me without informing the German services."

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

Moreover, Svetlana was convinced that for some reason Israel too intervened on her behalf and that the "Mossad asked the Germans to help me".

For the next four years, she lived in Germany and was subject to close surveillance by both the Germans and the Americans. Only then did she return to the country from which her family fled in the early 1970s, and in the meantime renounced the communist ideology and changed from the USSR to Russia. In her new-old country, she adopted the name Svetlana and finally parted with the name Yeta.

Even today, Svetlana remains fond of Israel, but for financial reasons, she chose not to settle in the country after the turbulent chapter in her life came to an end. Instead, at the beginning of the 2000s, she found a way to turn her good acquaintance with the West in general, and with Germany in particular, into a means of livelihood.

"I thought at the time that in a small country like Israel, the possibilities for me were limited to non-existent," she explained sadly. "While the area of economic cooperation between Germany and Russia seemed particularly promising, I organized seminars for businessmen from both sides so that they could find a common language and build profitable ventures. Worked quite well, but collapsed with the economic crisis of 2008."

For years, she has been angry with the SVR, Russia's spy service that came into the world in place of the KGB, which shirked its responsibility toward her and the obligation to pay her a pension. It seems that everyone has forgotten about her work, except for one person.

A man whom she saw for the second time on the television background when he took an oath as the president of the Russian Federation, she immediately recognized him as the same investigator from "Karlshorst." Vladimir Putin, a junior officer in the KGB at the time and the all-powerful president today, did indeed make up for his "English teacher at a rural school" remarks by granting Svetlana an apartment.