"You don't have black tea? Just all these infusions with fruit?" asked Professor Yoav Dotan in the café where we met. "The infusions are fantastic," the young woman advocated, but just like in his legal scholarship, Dotan prefers things in the original – authentic, precise, and without distortions.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

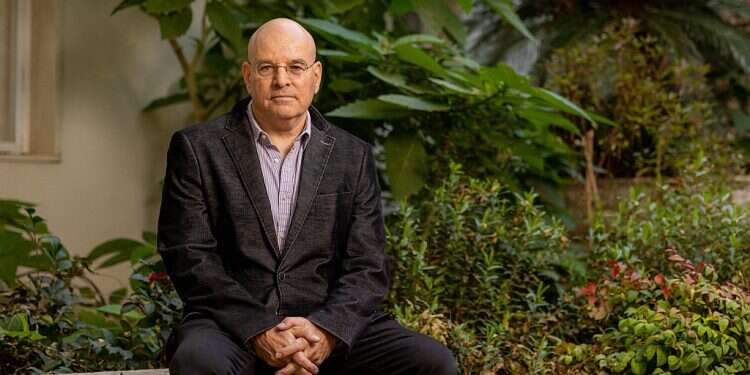

Professor Dotan is a lecturer and law researcher at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and is considered one of Israel's leading legal experts. Unlike most of his colleagues, he is one of the vocal critics of the High Court of Justice's worldview, which is called "judicial activism." His new book, "Judicial Review of Administrative Discretion", has recently come out.

"The ideas in it are hardly voiced elsewhere. Only a minority in the legal world think as I do," says Dotan, noting the late Ruth Gavison ("the most important jurist of the last generation") Daniel Friedmann, Gidi Sapir, Menny Mautner, and several others. More than identifying himself as conservative, Dotan defines himself as a textualist and as a judicial formalist. "The title of 'conservative jurist' essentially groups together the few jurists who are critical of judicial activism, which also, incidentally, is undefined. No one knows exactly what it is, but everyone understands that it is a derogatory term."

Q: Why are the conservative jurists the minority in academia and in the courts?

"A caravan emerged, the caravan of the rule of law, which is colorful, pretty, and magnificent, and it is much easier to join it. This simply exempts you from confrontation with the other jurists, and from critical thinking. It is easy to be an activist. You are always more enlightened, liberal, and moral. In the past, a PhD student in the faculty of law who held opinions like mine would not bother to make them conspicuous.

"Aharon Barak [the creator and leader of Israel's judicial activist camp] created a sense of harmonious theory. Balances. Law students constantly tell me "we need to balance" and I tell them that I am sorry, you obviously have the balancing gene, but I am apparently defective, I don't have it. I need to think to determine what is right and what is not."

Q: The jurists that you mentioned, who oppose judicial activism, are the older generation who came from the political Left, while the new generation of conservatives, such as Aviad Bakshi, Shuki Segev, and others, comes from the Right.

"I agree. Through the steps that the High Court has taken, it has turned itself into a main topic in the political debate. This is a serious mistake and did not happen by chance. When I began to criticize the justice system, my ideas were perceived as criticism, but not as a political cause. The justice system entered the political arena, and therefore support or criticism are [now] framed by a political camp. Gideon Sa'ar advocates right-wing positions on Israeli territorial sovereignty, but because of his attitude toward the justice system he has been identified as part of the LEft.

"Whoever expresses stances like those of Gavison and myself is identified as right-wing, which of course is a mistake. And if your opinions are like mine and you don't want to be pigeonholed with the political right, you simply don't express these opinions – that the court's presumptuousness in intervening in the mess of economic, social, security, and national problems, to impose order on them, is both problematic on the theoretical level and ineffective."

Reasonableness – Not what we knew

Dotan was born in 1959 and grew up in the Dan neighborhood of Tel Aviv. His mother was a piano teacher – something that planted in him a strong love for classical music that he retains to this day – while his father marketed mechanical equipment in Israel's textile industry, which was quite expansive in that period. Dotan's brother Erez eventually turned that business into a robotics company. The two brothers grew up in an upper-middle-class home that supported the Independent Liberals party.

He has served in senior academic positions, including as dean, at the Faculty of Law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and has won many awards. Today, Dotan lives in Modi'in with his wife and their three children.

As part of his opposition to activism, Dotan also objects to the High Court's use of the reasonableness doctrine when intervening in government decisions. In his book, Dotan differentiates between "reasonableness of outrageousness" – the court's intervention in a decision deemed deficient due to extreme unreasonableness, which Dotan supports – and the "balancing reasonableness" doctrine, through which the High Court overstepped its boundaries.

"The High Court took the accepted understanding of reasonableness – intervening when a government authority harms the citizen in an absurd and capricious manner – and turned it into something else entirely. Everyone must be reasonable, the government and the prime minister, except that they always think they are acting reasonably. The court's reasonableness approach states that the government will balance its own considerations and that the court will reverse-engineer the government's determination. In effect, the court becomes a second government that oversees the elected government, and in instances that have no bearing whatsoever on personal liberties. All the lawsuits filed by the Movement for Quality Government in Israel are not about personal liberties, but are rather claims that things should be done differently than the government is doing them."

Prof. Dotan demonstrates this with the "Deri-Pinhasi Precedent," a 1993 landmark ruling in which the High Court ordered then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin to fire Minister Aryeh Deri because the justices opined that it was unreasonable to appoint a person to a cabinet post if he had been indicted. "There is no parallel to that anywhere in the world," protests Dotan. "The pretentiousness of the court, to dictate norms to the political system and to step into the government's place, not only does not exist anywhere else but lacks any theoretical basis. It is comfortable to be in the position of the warriors against corruption, such that if someone criticizes them, then he supports corruption or is of dubious character. They call themselves the rule of law. In practice, it is the exact opposite, because the law is clear. This is the rule of the judge.

"My idea is based entirely on one statement: comparative institutional advantage. Does the court have a comparative institutional advantage over others? In government decisions, which are policy decisions, the court has no comparative advantage. Anyone who supports judicial activism supports judicial intervention in policy considerations because such a person thinks that the political results of the court decision are better than the government's results.

"I believe that the High Court can intervene only in questions of limited fundamental liberties which constitute the democratic framework: freedom of expression, the right to vote, freedom of the press, freedom of occupation and equality. The problem is that the High Court has turned everything into a right. Reasonableness should not be applied to government decisions unless they concern personal liberties. There is no reason to assume that the court's reasonableness is preferred to the reasonableness of the government, but rather the opposite."

A Pretend Constitution

In a few rulings of recent years, the High Court has moved toward intervening in the legislation of the Basic Laws, and Prof. Dotan objects to this, of course. "What is surprising here is not that the High Court is interfering in Basic Laws, but rather that it began doing so only recently. In the Bank Mizrahi decision in 1995, Aharon Barak said that from now on Basic Laws are a constitution. In other words, from now on, we can strike down regular laws because there is a constitution that gives us the power to do so. The "small" problem is that, unlike all the other constitutions in the world, the regular lawmaker can change this one by a vote of two against one. The moment you recognize that the High Court can strike down laws by virtue of the constitution, you have also recognized the legislator's ability to change it.

"Israel has no constitution that was legislated by a vast majority, and what kind of constitution is it where the court that bases its rulings on it can also intervene in its formation? The more time passes, the more the nakedness of Barak's approach is revealed." Dotan believes that only in very rare cases does the High Court theoretically have the option to strike down legal ordinances that contradict the most basic fundamentals of democracy, whether or not a constitution exists.

In the High Court of Justice's decision on the Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People, the justices said, "We have the option to interfere with a Basic Law," but they tried to tone this down by saying it is a very distant option, for use in particularly extreme cases. Still, Justice George Karra, in his minority opinion, determined that the Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People is that extreme case. There are no rules; the interference is already here.

"Yes, this is a problem, and for that reason an override clause is necessary. Every democracy has two components – the first and main one is the principle of self-government. Through our parliamentary representatives, we can determine public policy. The second component is that the majority cannot do just anything.

"In most of the systems, the court takes care of the second component, except then a problem arises: They've given a small group of judges, who were not elected by the public, the authority to strike down decisions of the majority. Who can guarantee that these judges will not turn into a band of tyrants themselves? This is tension that exists in every democracy, and the override clause is a possible mechanism that can neutralize this tension. Without that clause, we have a serious problem, because the court says it has the authority to interfere with Basic Laws and sets itself no limit."

Judicial intervention weakens

In his book, Dotan champions what he calls "alternative criticism mechanisms." There is no justification, he explains, for granting the court excessive powers, because it also makes mistakes, and in any event, there are other oversight mechanisms that restrict or influence the government; for example, the voter's decision at the polls, or civil protest. "Minister of Culture Miki Zohar wanted to cancel the funding for cultural activities on Shabbat and backtracked after a public outcry – and if he hadn't, within ten minutes a lawsuit would have been filed with the High Court. This is a petition on a subject that is not the court's business. The state didn't restrict the cultural consumption of individuals on the Shabbat, and it is the government's right to set policy for what it funds or not. No personal liberties were violated."

Q: We have fallen in love with turning to the court because the ruling brings an immediate resolution. On the other hand, conservatism prefers public criticism because it believes in long-term social processes.

"You're correct. In addition, a court ruling seems nice and clean, and there are honorable justices in robes in the courtroom. On the other hand, politics is dirty and smelly, you have the image of the Likud Central Committee, the deals. But that is democracy. The Likud Central Committee is more democratic than the High Court. I don't love that committee but look at the Likud conference. That is democracy. When the court interferes, it weakens those alternative criticism mechanisms. The Conscription Law, for example – jurists tend to assume that they can appeal to the High Court for it to provide a solution. That is an illusion and all the more so concerning wide-ranging social problems. The High Court cannot force 10% of the population to change its lifestyle."

It was recently reported that there have been discussions on the possibility of declaring the legal incapacitation of Netanyahu to serve as prime minister. Attorney General Gali Barhav-Miara clarified that no such discussions were held at all, and Dotan himself stresses that this would be an unrealistic scenario. "Netanyahu's indictments were at the heart of the elections, and the majority of the public preferred him as prime minister.

"After he has already been elected, to concoct shaky legal constructs of incapacitation, and use them as a basis for instigating tectonic change in Israeli politics – that is something that is inconceivable on the legal doctrine level. There is no source authority to declare a prime minister in a state of legal incapacitation, and such a thing cannot happen. I am also not one of his followers, to put it mildly, but the public elected him."

The men of absolute truth

Despite his opposition to judicial activism, last week Dotan stood on stage in the heart of Hebrew University and called on students to "go out and demonstrate." "My call surprised a lot of people," he says. "Yariv Levin's reforms include correct ideas, such as treating the issue of reasonableness, an overriding clause, and more, but what the reform offers is not overriding – it is a facade. It is elimination. The reform is sweeping and patently imbalanced. I am also troubled by the government's overall assault on all the bureaucratic institutions of the executive authority and beyond. I call to protest this. If the government backs down on most of the things I listed, we can sit together to discuss reducing the authority of the justice system, and it will be very clear where I stand."

Q: The justice system does not even accept your changes or those of Gavison or Justice Noam Sohlberg. It leaves no room for debate.

"True. I have been warning of that for years. The justice system donned iron gloves when dealing with anyone who tried to suggest any type of reform. Minister Levin tells himself, and correctly so, "If I don't act quickly and aggressively, at best I will end up like Daniel Friedmann, and at worst I will end up like Yaakov Neeman.' The wise are forewarned. I said that anyone who makes changes will be dealt with by the justice system the way it dealt with all his predecessors."

Q: Just a minute. Stop. You surprise me.

"I don't think there were conspiracies or the concocting of cases, but that does not change the fact that every politician who is appointed minister of justice or to some other major ministry is afraid that the attorney general will open an investigation against him. In other words, somehow it has transpired – somehow – that all sorts of politicians came to propose reforms, or even had just been appointed and were perceived as a threat and found themselves under police investigation. Suddenly there is a scandal in a newspaper, and the police investigate. It isn't just Neeman this happened to, it's Rubi Rivlin, it's Avigdor Kahalani and too many cases like this. I believe in the good faith of the prosecutors, but something doesn't make sense from the perspective of probability.

"Look what happened to Hila Gerstl, one of the most esteemed judges. She was appointed ombudsman of the State Attorney's Office, and the moment she showed that she was taking her job seriously – she was ousted in such an aggressive manner it was simply unbelievable. The justice system has turned everyone who suggested reforms into a fascist or a criminal, and if not into both those, then he is portrayed as delusional.

"This isn't coming from malice, but rather from a sense of deep personal conviction. 'The absolute truth is on my side, so it can't be that someone who disagrees with me is okay, or that he doesn't have some foreign interest. There's something that matters with him, because if he is okay, then the conclusion would be that maybe I'm not okay. If Yoav Dotan criticizes the justice system, it can't be that he's making a good-faith claim that there's a problem with the judicial activism approach. Something must be wrong with Dotan.'"

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!