The Russian military's failure to seize the Ukrainian capital was inevitable because in the preceding years they had never directly faced a powerful enemy, a former mercenary with the Kremlin-linked Wagner Group who fought alongside the Russian military said.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

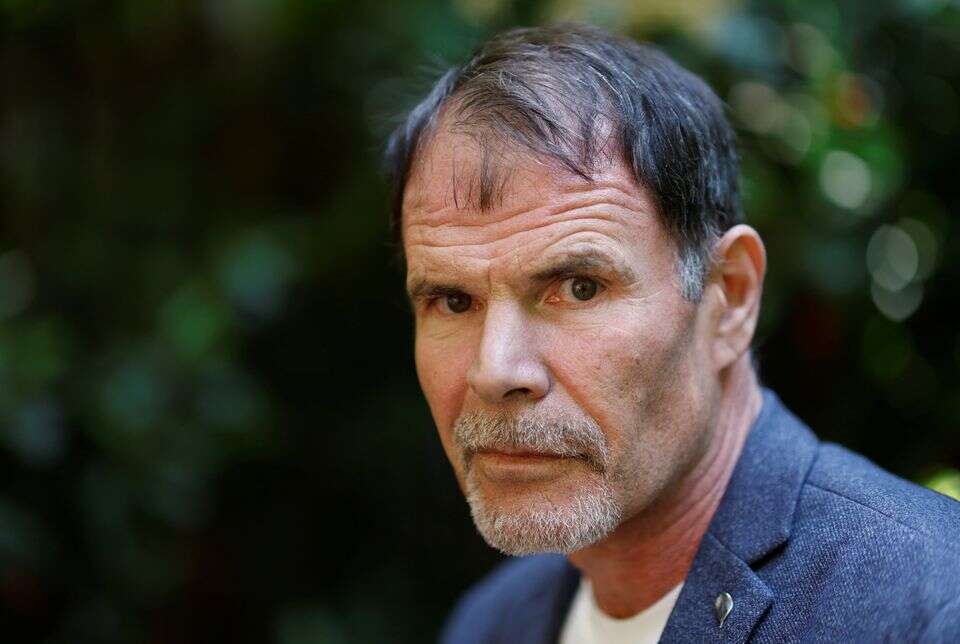

Marat Gabidullin took part in Wagner Group missions on the Kremlin's behalf in Syria and a previous conflict in Ukraine, before deciding to go public about his experience inside the secretive private military company.

Gabidullin, 55, quit the Wagner group in 2019, but several months before Russia launched the invasion on Feb. 24 he said he received a call from a recruiter who invited him to go back to fighting as a mercenary in Ukraine.

He refused, in part because, he said, he knew Russian forces were not up to the job, even though they trumpeted their arsenal of new weapons and their successes in Syria where they helped President Bashar Assad defeat an armed rebellion.

"They were caught completely by surprise that the Ukrainian military resisted so fiercely and that they faced an actual army," Gabidullin said, adding that people he spoke to on the Russian side had told him they expected to face rag-tag militias when they invaded Ukraine, not well-drilled regular troops.

"I told them: 'Guys, that's a mistake'," said Gabidullin, who is now in France where he is publishing a book about his experiences fighting with the Wagner Group.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said he did not know who Gabidullin was and whether he has ever been a member of private military companies.

"We, the state, the government, the Kremlin cannot have anything to do with it," he said.

The Russian Defense Ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

Gabidullin is part of a small but growing cohort of people in Russia with security backgrounds who have supported President Vladimir Putin's foreign incursions but now say the way the war is being conducted is incompetent.

Igor Girkin, who helped lead a pro-Kremlin armed revolt in eastern Ukraine in 2014, has been critical of the way this campaign is being conducted. Alexei Alexandrov, an architect of the 2014 rebellion, told Reuters in March the invasion was a mistake.

Gabidullin took part in some of the bloodiest Syrian clashes in Deir al-Zor province, in Ghouta, and near the ancient city of Palmyra. He was seriously injured in 2016 when a grenade exploded behind his back during a battle in the mountains near Latakia.

He spent a week in a coma and three months in a hospital where he had surgeries to remove one of his kidneys and some intestines. Reuters has independently verified he was in the Wagner Group and was in combat in Syria.

Wagner Group fighters have been accused by rights groups and the Ukrainian government of committing war crimes in Syria and eastern Ukraine from 2014 onwards. Gabidullin said he had never been involved in such abuses.

Moscow's involvement helped turn the tide of the Syrian war in favor of Assad, but Gabidullin said Russia's military restricted itself mainly to attacks from the air while relying on Wagner mercenaries and other proxies to do the lion's share of the fighting on the ground.

The Russian military's task was easier too. Its opponents – the Islamic State and other militias – had no anti-aircraft systems or artillery.

Fighting Ukraine, he said, was a different proposition.

"I've seen enough of them in Syria... [The Russian military] didn't take part in combat directly," he said in an interview in Paris to promote his book, which will be published by French publishing house Michel Lafon this month.

"The military forces .... when it was needed to learn how to fight, did not learn how to fight for real," he said.

Wagner Group is an informal entity, with – on paper at least – no offices or staff. The US Treasury Department and the European Union have said the Wagner Group is linked to Russian businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin. Prigozhin has denied any such links.

Concord Management and Consulting, Prigozhin's main business, did not respond to a request for comment.

Putin has said private military contractors have the right to work and pursue their interests anywhere in the world as long as they do not break Russian law. He has also said that Wagner Group neither represented the Russian state nor was paid by it.

Gabidullin said although he had known the Russian invasion of Ukraine was coming, he did not expect it to be on such a scale.

"I could not even think that Russia will wage a war on Ukraine. How could that be? It's impossible," he said.

Meanwhile, Ukraine's natural gas pipeline operator on Wednesday stopped Russian shipments through a key hub in the east of the country, while its president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, said Kyiv's military had made small gains, pushing Russian forces out of four villages near Kharkiv.

The pipeline operator said Russian shipments through its Novopskov hub, in an area controlled by Moscow-backed separatists, would be cut beginning Wednesday. It said the hub handles about a third of Russian gas passing through Ukraine to Western Europe. Russia's state-owned natural gas giant Gazprom put the figure at about a quarter.

The move marks the first time natural gas supply has been affected by the war that began in February. It may force Russia to shift flows of its gas through territory controlled by Ukraine to reach its clients in Europe. Russia's state energy giant Gazprom initially said it couldn't, though preliminary flow data suggested higher rates moving through a second station in Ukrainian-controlled territory.

The operator said it was stopping the flow because of interference from "occupying forces," including the apparent siphoning of gas. Russia could reroute shipments through Sudzha, a main hub in a northern part of the country controlled by Ukraine, it said. But Gazprom spokesperson Sergei Kupriyanov said that would be "technologically impossible" and questioned the reason given for the stoppage.

Zelenskyy said Tuesday that the military was gradually pushing Russian troops away from Kharkiv, while Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba voiced what appeared to be increasing confidence – and expanded goals, suggesting Ukraine could go beyond just forcing Russia back to areas it held before the invasion began 11 weeks ago.

Kuleba told the Financial Times that Ukraine initially believed victory would be the withdrawal of Russian troops to positions they occupied before the Feb. 24 invasion. But the focus shifted to the eastern industrial heartland of the Donbas after Russian forces failed to take Kyiv early in the war.

"Now if we are strong enough on the military front, and we win the battle for Donbas, which will be crucial for the following dynamics of the war, of course the victory for us in this war will be the liberation of the rest of our territories," he said.

Kuleba's statement seemed to reflect political ambitions more than battlefield realities: Russian forces have made advances in the Donbas and control more of it than they did before the war began. But it highlights how Ukraine has stymied a larger, better-armed Russian military, surprising many who had anticipated a much quicker end to the conflict.

Ukraine said Tuesday that Russian forces fired seven missiles at Odesa a day earlier, hitting a shopping center and a warehouse in the country's largest port. One person was killed and five wounded, the military said.

Images showed a burning building and debris – including a tennis shoe – in a heap of destruction in the city on the Black Sea.

One general has suggested Moscow's aims include cutting Ukraine's maritime access to both the Black and Azov seas. That would also give Russia a corridor linking it to both the Crimean Peninsula, which it seized in 2014, and Transnistria, a pro-Moscow region of Moldova.

Ukraine's targeting of Russian forces on Snake Island in the Black Sea was helping disrupt Moscow's attempts to expand its influence, the British military said.

Russia has sought to reinforce its garrison on Snake Island, while "Ukraine has successfully struck Russian air defenses and resupply vessels with Bayraktar drones," the British Defense Ministry said in an intelligence update on Twitter. It said Russian resupply vessels had minimum protection after the Russian Navy retreated to Crimea after losing the Moskva.

But the British military warned: "If Russia consolidates its position on [Snake] Island with strategic air defense and coastal defense cruise missiles, they could dominate the northwestern Black Sea."

Even if Russia fails to sever Ukraine from its coast – and it appears to lack the forces to do so – continuing missile strikes on Odesa reflect its strategic importance. The Russian military has repeatedly targeted its airport, claiming it destroyed several batches of Western weapons.

Odesa is a major gateway for grain shipments, and the Russian blockade threatens global food supplies. It's also a cultural jewel, dear to Ukrainians and Russians alike. Targeting it carries symbolic significance.

To protect Odesa, Kyiv might need to shift forces to the southwest, drawing them away from the eastern front in the Donbas, where they are fighting near Kharkiv to push the Russians back across the border.

Kharkiv and its surroundings have been under sustained Russian attack since the early in the war. In recent weeks, grisly pictures testified to the horrors of those battles, with charred and mangled bodies strewn in one street.

The bodies of 44 civilians were found in the rubble of a five-story building that collapsed in March in Izyum, about 120 kilometers (75 miles) from Kharkiv, Oleh Synehubov, head of the regional administration, said Tuesday.

Russian aircraft twice launched unguided missiles Tuesday at the Sumy area northeast of Kharkiv, according to the Ukrainian border guard service. The region's governor said the missiles hit several residential buildings, but no one was killed. Russian mortars hit the Chernihiv region, along the Ukrainian border with Belarus, but there was no word on casualties.

Zelenskyy used his nightly address to pay tribute to Leonid Kravchuk, the first president of an independent Ukraine, who died Tuesday at 88. Kravchuk showed courage and knew how to get the country to listen to him, he said.

That was particularly important in "crisis moments, when the future of the whole country may depend on the courage of one man," said Zelenskyy, whose own communication skills and decision to remain in Kyiv when it came under Russian attack helped make him a strong wartime leader.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

In related news, the World Health Organization's European region passed a resolution on Tuesday, possibly resulting in the closure of Russia's regional office and the suspension of meetings in the country in response to its invasion of Ukraine.

The special session of the European region passed the resolution, supported by Ukraine and the European Union, with 43 in favor and three against (Russia, Belarus, Tajikistan) and two abstentions.

This is considered by backers to be an important political step to isolate Moscow, and they said they were at pains to avoid any significant impact on Russia's health system.

The resolution referred to a "health emergency" in Ukraine, noting mass casualties as well as risks of chronic and infectious diseases that have resulted from Russia's military actions.

Russia's envoy Andrey Plutnitsky opposed the resolution and said he was "extremely disappointed."

"We believe this is a huge moment of harm for the system of global healthcare," he told the meeting of members and top WHO officials, Reuters reported.

Some criticize the resolution, saying it does not go far enough. Diplomats told Reuters they had dropped efforts to suspend Russia from the WHO executive board due to legal technicalities. However, members could seek to freeze Russia's voting rights at a major meeting later this month.

i24NEWS contributed to this report.