The history of the cave of Shimon HaTzadik (Simeon the Righteous) is full of miracles and folklore, but one unknown event that today would no doubt be seen as a miracle took place in the neighborhood in the 1940s and its impact is still being felt. For a few weeks, several dozen Arab families helped their Jewish neighbors file documents and papers to establish a Jewish neighborhood right next to their own houses.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Today, with the Shimon HaTzadik neighborhood a synonym for "powder keg" and a focal point for clashes between Jews and Arabs, it's difficult to imagine something like this happening. But the previously unknown historical reports filed by Yitzhak Alexanderoni, one of the heads of the housing committee of the small Jewish neighborhood, reveal a story of Jewish-Arab cooperation for exactly that purpose. The story is revealed in a new book, Simon the Righteous, the Man and the Neighborhood, by Reut Odem.

The year was 1946, just two years before the establishment of the State of Israel. The Sephardi Community Council of Jerusalem, of which Alexandroni was a member, was trying to establish a Jewish neighborhood on the lands of Shimon HaTzadik, which had been purchased 70 years earlier by the Ashkenazi and Sephardi community councils. The housing committee sought to destroy the old and dilapidated houses and construct a new neighborhood.

To push forward the plan, the housing committee had to register the Jewish lands in Shimon HaTzadik under the legal entity of the "community council." Until then, plots had been registered individually under the names of the members of the council. Chartered surveyors from the architectural office of Hacker and Yalin went out to the neighborhood and nobody threw stones or firebombs at them. The Jews went door to door to their Arab neighbors, who signed the plans for them. Nobody saw them as "collaborators" or traitors to be sentenced to death.

Signatures were gathered from all the Arab landowners whose plots shared boundaries with the plots owned by the Jews. Among those who signed were the Nashashibi family, a Jerusalemite family of great standing and prestige. The Muslim Waqf (religious trust) and Arab and foreign residents of the American colony also signed the plans. Their signatures imply recognition of Jewish ownership of the land.

Today, this would no doubt be considered astonishing, but then, it was accepted as perfectly natural. After all the signatures were collected and deposited with the land registration office, the Mandate ministry of housing approved the building plans for the Jewish neighborhood, the construction of which probably would have gone ahead had it not been for the War of Independence. As we know, the lands of Shimon HaTzadik and Nahlat were torn away from Jewish Jerusalem and fell into Jordanian hands.

But the story of the contested neighborhood does not begin or end here. Odem's new book, published by the Reshit Jerusalem Seminary, exposes new and fascinating chapters in the history of the two small Jewish neighborhoods on the route to Mount Scopus. The study, due to be published in the coming weeks, shows that on July 14, 1944, two years before Alexandroni deposited the plans with the signatures of his Arab neighbors with the land registration office, the Irgun blew up the offices of the British Criminal Investigation Department at the Palace building in Jerusalem, an event that would play a critical role in the status of the contested lands in Shimon HaTzadik.

The explosion destroyed part of the building and also set off a fire in which most of the files in the land registration office of the British mandate were destroyed. Even though Alexandroni and his colleagues had deposited the plans with the land registration office, the damage caused in the attack to the original documents prevented the registration of Jewish ownership of the plots in Shimon HaTzadik and Nahlat Shimon. Moreover, the results of the underground attack against the land registration offices would turn out to have long-term consequences.

A Gibraltese-Jewish twist

Some 28 years after the explosion, the loss of the documents caused a big headache for the Custodian General of the State of Israel, who was in charge of the plots in Shimon HaTzadik and after the 1967 Six-Day War and was asked to restore them to their original owners (The Custodian General held the properties as the successor to the Jordanian custodian for enemy assets).

At first, in the absence of the original documents were lost in the fire caused by the attack, the Custodian General was unable to restore the plots to the owners, and it was only after a long period that a legal solution was found to return the lands to the Ashkenazi and Sephardi Community Councils.

The bombing carried out by the Irgun 78 years ago, which destroyed entire files in the land registration office, had hidden echoes in the most recent Supreme Court hearing on the dispute in Shimon HaTzadik. The Supreme Court justices did not dispute the Jewish ownership of the land, which leans on registration of property tax and elsewhere, but decided to allow the Arab residents who after the war were housed in Jewish homes to continue living there for now.

In practice, the judges relied on the fact that there is no registration in the land registry (as it was lost in the Irgun bombing) to prevent the eviction of Arab families from Jewish homes. They ordered an injunction on evictions until the proceedings until the Justice Ministry completes the land registry proces. It may well be that the signatures of Alexandroni's neighbors so many years ago will help restore the homes to their Jewish owners.

Odem's study provides another surprise that poses a historic question mark (albeit not a legal one) on why the Jews had to purchase the land in the first place at the end of the 19th century. According to one version, that of the historian and documentarist of Jewish life in Jerusalem, Pinchas Grayevsky, the famous deal to purchase the land was in fact an exceptional payment of compensation to an Arab who had illegally occupied it.

What appears to strengthen Grayevsky's claim are reports from the time that Muslims forced Jews to pay protection and imposed other restrictions on Jewish visitors to the grave of Simeon the Righteous, and the fact that over the centuries, the area, even before the land was purchased by Jews was called "al Yehoudiya."

Grayevsky (1873-1941) claimed that the deal came about following "a proposal by the Turkish governor of Jerusalem, to the Jewish communities to buy the land and the cave together with the trees and everything else on the plot."

The wording of the sales note shows us that in 1292 of the Hijri (1875 in the Islamic calendar) the plot was purchased from Sheikh Razak and his brothers and that the buyers were the Hacham Bashi Rabbi Avraham Ashkenazi of the Sephardi community and the Rabbi Meir Aurbach of the Ashkenazi community. The two bodies that purchased "the trees and everything else on the plot" had to pay 24 kiram and the land was purchased as an eternal religious trust for the Jewish community.

While the purchase of the holy site was a joyful occasion, Odem's study reveals that it also came under criticism. It was opposed by the poor of Jerusalem, who studied Torah during the day and relied for a living on the distribution of funds collected for them by Jewish communities around the world. The editor of the Hassidic periodical HaHavatzlet, Israel Dov Frumkin, was in those days a the mouthpiece for the poor of Jerusalem. He wondered whether "now [was] the time to expend great sums on building new houses of prayer? Buying fields, vineyards, and orchards where, according to legend, one of the ancients is buried. And this at a time when hunger and great expense are oppressing the souls of the residents of our city." (The houses of the neighborhood were incidentally built with funds donated by the Jews of Gibraltar).

Jerusalemite paracetamol

The book's author, Reut Odem, is a doctoral student at the Faculty of Land of Israel Studies at Bar Ilan University. She is a resident of Neve Tzuf in Binyamin. In the past, she lived with her family in Shimon HaTzadik, but her research deals with history, not politics. The present-day connections she insists are to be left to the interpretation of the readers and the author of this article.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

Odem describes the grave of Simeon the Righteous, the Mishnaic sage from the beginning of the Second Temple era, as a "Jerusalemite paracetamol." The cave in which he is buried became from the 14th century a place of supplication and prayer, to which many Jews and others came to pray for healing, salvation, and miracles and to prostrate on the grave of the High Priest, one of the last members of the Great Assembly, who was buried there in the sixth century BCE.

The elevated status of Simeon the Righteous is described in the Talmudic tractate, Yoma, and in the Book of Josippon, written in the Middle Ages. Josippon described a meeting that is said to have taken place in the temple between Alexander the Great and Simeon the Righteous. It is described as a meeting between two cultures, the Jewish culture and the Hellenistic culture, between monotheism and polytheism.

At the meeting, Alexander the Great is struck with awe at the sight in front of him. He blesses the God of Israel and asks Simeon the Righteous to eternalize his name in the temple by building a statue of him there. Simeon refuses and suggests an alternative that Alexander agrees to: "Your memory will be all the children of priests born in this year throughout Judea and Jerusalem shall be called Alexander in your name, and shall serve as a memory when they come to worship in the house of God, in this house, because we have no license from the God of this house, the Lord of Hosts to build any statue or image."

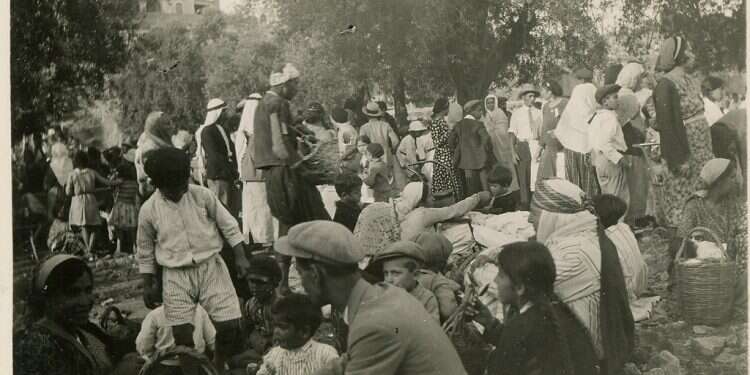

Odem notes that the many historical testimonies to the Jewish presence in Shimon HaTzadik focus on the celebrations that were held there several times a year, primarily on the festival of Lag B'Omer – where the ceremony of cutting a male child's hair for the first time at the age of three would be held – and on the day after Shavuot. The site was surrounded by ancient oak treesת and Muslims and Christians would often watch from the sidelines.

The proximity between the residents of the Nahשlat Shimon and Shimon HaTzadik neighborhoods and the aristocratic Nashashibi family created good neighborly relations. The Nashashibis and the Jews knew each other by name and took part in each other's celebrations. Jewish residents remember the Nashashibis buying matza on Passover and coming to ritually cleanse the Jews' utensils before Passover and even taking part in Lag B'Omer celebrations. Yona Cohen, a native resident and the son of Hacham Gershon, who would later become a correspondent for the newspaper HaTzofeh, wrote in his book, Hacham Gershon of Nahlat Shimon that the neighborly relations between the Jews of Shimon HaTzadik and the Arabs of Sheikh Jarrah were friendly.

He said that ties were not harmed by the years of tension, by the 1929 riots or the Great Revolt (1936 -1939). Gershon's nephew, the journalist Haggai Huberman, relates that he heard from his aunt Leah Goldberger (Gershon's daughter) about Arab herders who would come to water their flocks at the wells in the courtyards of the Jews and about the Arabs who came to the doors of the Jews with buckets of milk and poured our their wares.

But as with current events in Shimon HaTzadik and Sheikh Jarrah, troubles from outside, not from the local residents. If today it is Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, in those days, before the establishment of the state, it was Arab gangs. In her book, Odem describes battles in the area during the War of Independence and the Six-Day War. "Very few people, she complains, "have been exposed to the legacy of the battles that took place here. The IDF teachers about the battles that went on here, but the soldiers don't come to see for themselves on the ground where they took place."

An art student and commander

The documentation in Odem's book shows that the Haganah placed great importance on these two neighborhoods in its defense of Jewish Jerusalem, and as a bridge to Mount Scopus (which was cut off from the rest of Jerusalem after the War of Independence and became an Israeli enclave with special arrangements in the heart of the Jordanian held part of the city).

The commander of the Shimon HaTzadik neighborhood was Azaria (Jimmy) Marimchek, a student of graphic design at the Bezalel Academy of Arts, who was killed in a battle in the summer of 1948 after being hit by a mortar shell in Ma'alei HaHahamisha. But the most fascinating figure this book deals with is that of Yaakov Shviki, who would mix with the Arabs of the area and was one of the heroes of the neighborhood. Shviki was born in the Old City and was a member of the Haganah who stood out as a "strong and upright man, well dressed and with a shabaria dagger, who never renounced Jewish honor."

The most prominent incident that Shviki was involved in happened during the period of the Great Arab Revolt. One day he found out that Arab rioters were gathering outside of the neighborhood and were planning to attack Jewish homes in Shimon HaTzadik. Shviki and his friends dressed up as Arabs went out to the heart of the Arab area and entered a cafe where a gang of Arabs was sitting.

"We heard things are going to be happening tonight," Shviki said to them in Arabic. "We've come from the village to help out a bit." Shviki had told the Haganah headquarters not to shoot the assailants. "We'll mingle with them and we'll manage alone," he reported. "At night, the gang started moving in the direction of Nahlat Shimon. The bottom line was published the following day in the papers: "A gang of Arabs has been eliminated. The police are investigating."

The Haganah had built a cache with many weapons in Shviki's home that served in the defense of Shimon HaTazdik and Nahlat Shimon. The house also served the Haganah as a gathering point for the local commanders. The secret cache completely upset the routine of Shviki's family. At night, strangers would come, and during the day, the family would live in constant fear of the house being searched. In order not to arouse suspicion, Shviki's wife would buy lots of goods at a nearby Arab grocery, supposedly for her family.

Once, when she was surprised by the British, she put pistols in a pot full of water, covered it quickly in with vegetables, and put it to cook on an oil stove. After the Six-Day War, Shviki's son Moshe uncovered the Haganah cache in the house, which was now occupied by Arabs. Yaakov Shviki himself was killed in July 1940 by Arab rioters near Nahal Zohar in the Dead Sea Basin together with George Blake, a British geologist he was escorting.

During the War of Independence, the residents of Shimon HaTzadik open their homes to the fighters of the Haganah. The organization's headquarters were located in the synagogue of the Georgian community, where the neighborhood youth and their commanders practiced dismantling and assembling weapons. The lookout whose job was to warn of British patrols was the local teacher and the cantor of the synagogue, Hacham Gershon.

As there weren't many weapons, long sticks were placed in the windows of the second floor of the Aleppo community synagogue in the neighborhood. From a distance the sticks looked like rifles and the treasurer of the synagogue would make loud clicking noises to create the impression that the neighborhood was well guarded and armed with modern weapons. But in January 1948, after a fierce attack from the direction of Sheikh Jarrah, the British confiscated many real weapons and arrested 21 defenders of the neighborhood.

The intensifying battles led to the Jews being evacuated from their homes at the order of the British. Jews were no longer able to even visit the cave of Simeon the Righteous. The neighborhood's residents became refugees and would later receive apartments in the Arab neighborhoods Katamon, Talbiyeh, and Romema, whose residents had fled.

Immediately after the Six-Day War, the state paid compensation to four families living in the area of the grave and evicted them from there. That same year tens of thousands of people came to visit the tomb. The Talna Hassidic court headed by Rabbi Yohanan Twersky was the first to transfer its Beit Midrash to the ruins of the Sephardi synagogue, but a year later, they left.

The return of Jews to their homes in Shimon HaTzadik began in earnest in October 1998, 31 years after the Six-Day War, when a group of Jewish hikers who had come to visit the abandoned synagogue noticed one of the Arab neighbors trying to annex the synagogue structure to his home and carrying out construction work there. The late MK Benny Elon (1954 to 2017) led the battle to have the synagogue and Jewish property in the neighborhood returned to its owners. Alon received the authorization of the Sephardi Community Council to renovate the structure and make it reusable.

The rest of the history of Shimon HaTzadik is written in the chronicles of the Jewish-Arab struggle for Jerusalem that continues to this very day. Some 23 years after Elon and his yeshiva students entered the synagogue, 21 Jewish families live in the eye of the storm in Shimon HaTzadik and Nahlat Shimon, just a seventh of the 140 families who lived in these two neighborhoods in their glory days on the eve of the War of Independence.