One of the possible future war scenarios presented to the political leadership a few months ago described Hezbollah firing thousands of lethal missiles a day at Israeli population centers, damaging strategic sites, destroying hundreds of homes, and causing heavy losses and wounded – all against a backdrop of chaos, with Arab Israeli rioting that would make the events of last May look like a child's game.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

The scenario envisioned Hezbollah trying to capture territory and communities in northern Israel, while Hamas in Gaza would be shooting rockets at population centers in the south of the country. One of the cabinet ministers at the presentation asked when the US last restocked its emergency ammunition supplies in Israel, which Israel also relies on during wars. He mentioned that in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, European countries refused to allow American planes carrying weapons to Israel to refuel within their borders.

The minister also mentioned that during Operation Protective Edge in 2014, the Obama administration prevented weapons from being sent to Israel and thinned out Israel's reserves of rockets and mortars, claiming that the Israeli ammunition, which had come from the US, was hitting and killing civilians in the Gaza Strip. The same minister also wondered how the US would act in a scenario such as this, if Israel were forced to defend itself.

These recollections resurfaced this week following Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the weakness the US and the west demonstrated in countering it. In sidebar chats, the ministers wondered if the US was still an ally on which Israel could depend, and to what extent. Is the long-discussed possibility of a defense pact still relevant? And will Israel's limited cooperation with NATO, of which it is not a member, help it if and when the country is in distress?

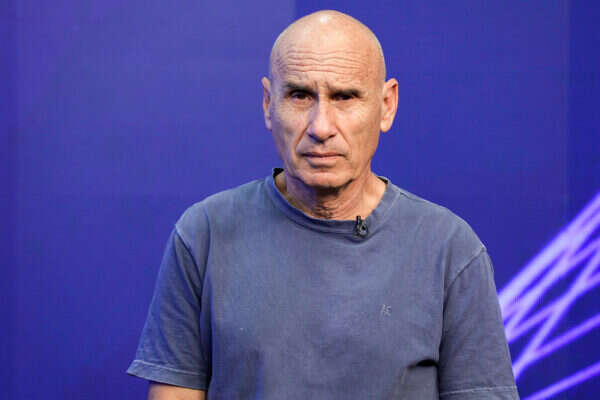

"The US is weakened and withdrawing into itself," says Professor Eytan Gilboa, an expert on the US and international relations at Bar-Ilan University. "The process that began during Obama's presidency continued under Trump and is growing stronger under Biden. Obama said it as clearly as possible – American cannot and does not want to be the world's policeman.

"The US is changing," Gilboa assesses. "And not to our [Israel's] benefit. The fact that it is increasingly becoming a country of minorities – Hispanics, Blacks, and Asians – works against us. The general American public, including the Jewish public, particularly the young people, are less and less committed to Israel. Even the Evangelicals aren't what they used to be. Support for us has waned, and will wane further.

"As someone who has been examining US conduct for decades, I am now seeing significant weakness," Gilboa says. "Trump, I remind everyone, went against NATO and the EU, and only a few days ago said Putin was a genius. Trump's America also allowed the Turks to run roughshod over the Kurds in northern Syria, which was seen as an abandonment of its Kurdish friends, who were allies in the war against Islamic State."

Q: Is Israel an exception to the process you are describing?

"Right now, we are. They are still investing in us, a lot. In the longer term, what I described is the true direction, and we should internalize that."

Q: Only two years ago, there was talk here about a defense pact between us and the Americans. Is that still relevant?

"The possibility of a defense pact comes up from time to time as a cure and as compensation for territorial concessions. As long as 40 years ago, when I was managing a drill at the Israel National Defense College that played out Israel conceding territory in exchange for international commitments – I thought that trading territory for a pact with the US was foolishness of the first rank. We don't need American soldiers. We need weapons. Even now, Israel isn't getting all the weapons it needs. The Americans are holding up shipments of refueling aircraft, which could be relevant if we take action against Iran, and aren't supplying us with bunker busters, like we asked for."

'A shaky wall'

"A defense pact wouldn't be worth the paper it's written on," Gilboa thinks. "If there is a pact and they don't want to help, they won't. And if there is an acute need for their aid and they do want to help, they will, even without a pact."

Q: Are the defense and security understandings currently in place between Israel and the US something we can count on?

"Less and less. The West and Biden thought that the age of wars was over, and under their noses a war started that is reminiscent of World War II. Luckily for us, we don't currently have a defense pact with the US or NATO. They'd tell the Israeli Air Force, come save the Baltic states. A defense pact adds commitments we don't need, and could limit us, such as on the Golan Heights or in Gaza. Imagine what would have happened if [Menachem] Begin had needed to consult with the US and get its permission before deciding to bomb the Iraqi nuclear reactor. The Americans would very likely have torpedoed that."

Maj. Gen. (res.) Gershon Hacohen, former head of the IDF's Military Colleges, is one of the strongest opponents of a defense pact with the US, or any other dependence on it. Such a pact, he says, would "completely bind Israel to American interests."

Even now, Hacohen says, "the US wants to see a puppet government here [in Israel], in the sense that we would comply with their view of Israel's defense needs and forgo our vital interests according to their wishes. Currently, even before any defense pact, the Americans aren't allowing us to build in Atarot in northern Jerusalem or Pisgat Zeev or in Judea and Samaria, which are not only the homeland, but also crucial security zones for us, existential needs. Imagine what would happen if we were to bind ourselves to closer agreements with them. A military alliance would force us to take risks and tie us down to constant pressure to make deals that involve withdrawing from territories."

Hacohen does not trust the US: "Reality is dynamic, and the struggle is constant. Interests change. Look at how the Druze have survived, by sticking to the aphorism, 'We are with the wall that stands strong.' No one wants to lean on a shaky wall."

Q: Is the US of today a shaky wall?

"Yes, and it didn't start today. They didn't help us in the War of Independence. In the Sinai campaign they forced us to make an unconditional withdrawal, which eventually led us into the [1967] Six-Day War, where the victory was so quick they didn't have time to intervene. In the Yom Kippur War we could have achieved more, if [Henry] Kissinger hadn't interfered. Under [Benjamin] Netanyahu, they tried to get us to pull out of most of Judea and Samaria and force us, through Gen. John Allen, the former commander of the international forces in Afghanistan, to accept a western contingent of forces in the Jordan Valley. The US has also left Israel pretty much on its own in the fight to keep Iran from entrenching itself in Syria."

Q: You don't see any advantage to a defense agreement with the US?

"The Arabs might take into account that America supposedly stands behind us and will be somewhat more deterred, but we would pay too high a price for what we would get."

Maj. Gen. (res.) Yaakov Amidror, former head of the National Security Council and head of the Military Intelligence Directorate's Research Department, and now a senior researcher at the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security, suggests not dismissing – even now – the US's standing in the Middle East and the understandings and exist between the US and Israel.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

"The US is still the strongest country in the world. It sends us billions of dollars each year, and is the foreign country with the most forces in the Middle East. We don't have a defense pact with them, but when it comes to intelligence, we cooperate with them and break down imaginary barriers. There aren't many countries in the world that cooperate with the US on research and technology and military industry like Israel does. They are developing the Arrow 3 and David's Sling [missile defense systems] with us, and there is also the law to preserve Israel's qualitative military advantage that requires the administration to report every year if and how it is preserving our edge. I know of at least one instance in which they didn't sell an Arab country a certain kind of weapon because we convinced them it would affect our qualitative advantage," Amidror says.

'Americans, go home'

Amidror mentions an agreement between the US and Israel, which is designed to allow the Americans to store ammunition in the Middle East, including Israel. "Should an event require it, the US can use those munitions, and if Israel finds itself in an emergency situation, it would be easier for them to allow us to use them as backup. We just need to make sure they don't become outdated," he says.

Q: Is the US agreeing to our requests to purchase advanced weaponry?

"There is no country in the world that sells all the weapons it develops. We also produce [weapons] that we will never sell to others. Countries always keep something for themselves. They agreed to sell us the midair refueling aircraft, which still aren't in production. I don't know of any holdup on the American side."

Q: Bunker busters?

"I don't know of any delay on those, either. They have a giant bomb that we can't carry on our aircraft, so we don't have it."

Q: A defense pact with the US?

"Israel was built on the binding statement of its founders that we will fight on our own, and will not ask foreign soldiers, especially not Americans, to defend us. A defense pact of the kind you mention would hurt our commitment to defend ourselves and one of our strongest points in dealing with the US. Israel shouldn't do that to itself, and moreover, we want to retain our freedom of action, and have a different approach from most other countries. To prevent threats against us from becoming an actuality, we take action in places, at times and in ways that no other country does, do crazy things. According to foreign reports, we are constantly carrying out strikes in other states. What country does things like that? If there were a defense pact, there would be support but also commitments, and we couldn't go nuts when we needed to, and wouldn't be free to act. So there are more disadvantages than advantages to an alliance like that."

Q: Is the US, our great friend, still an entity that Israel can count on in times of trouble?

"There is a discrepancy between expectations and what the Americans give. The Americans, the policeman of the world, have been paying the price for 100 years. There is almost no war in the world that didn't cost the Americans and when it was over, all they got was, 'Yankees, go home!' In the past 100 years, the US hasn't kept a scrap of land anywhere it fought. Here, the Left thinks that the Americans are colonialists, and the Right – that they aren't reliable, but I don't know of any country that had an alliance with the US – an actual alliance, not just a friendship – whose aid the US didn't come to.

"The US didn't have a defense pact with Ukraine, or with the government in Afghanistan, or with the Kurds in Turkey. There were understandings, there was friendship, but no binding alliance, in writing. So then the US decides if and how to help friends in distress. At the same time, US demographics are changing dramatically … when we take it all into account, it's easier to understand why America, which is internally divided, is less thrilled about carrying the burden."

Q: Is that the direction? The US is weak, and will get weaker?

"More than the US is getting weaker, it has less desire to use the power it does have. What is weakened is the willingness to use its enormous military forces. When we look at the last 100 years and the processes currently taking place in the US, we understand why."

Q: So it's inappropriate to expect the US and NATO to help a friend in trouble with Russia?

"As long as there's no alliance, no country has any obligation to any other country. We won't send military forces to defend a country that's only a friend, either. Europe has no real ability to help. They barely have a military. The Germans only have a few hundred tanks. France has no real ability to deploy in the world, and neither do we. The only country in the world that is capable of intervening for long periods is the US, and to some extent Russia. The Americans are built for it. They can move their air force. All the sailors in the Israeli Navy would fit on one US aircraft carrier, and there would still be space left over."

Q: In light of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, how does all that affect Israel?

"Very little, if at all. We aren't part of Europe or NATO, despite our ties with them and our special relationship with the US. We should aspire to maintain and upgrade that relationship, but not to the level of mutual defense agreements, because they entail a lot of disadvantages for us. Our strength – at home and abroad – is that we fight independently, and so are also independent when it comes to our decision making and operations."

Brig. Gen. (res.) Yossi Kuperwasser, formerly head of the Military Intelligence Research Division and a former director-general of the Strategic Affairs Ministry, has a unique perspective on Israel's defense and security relations with the US. Kuperwasser used to serve as the IDF's intelligence attaché to Washington, and currently focuses on questions like these as a senior researcher at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Kuperwasser plays down expectations: "If Israel gets into real trouble, the Israel expectation will be for the US to back us up diplomatically and provide massive military aid in the form of weapons. Not American soldiers by any stretch of the imagination. It's not good for us, and not good for them," he says.

"One of the main problems is that there used to be an unwritten understanding that Israel would handle short-range threats from neighboring countries on its own, while the US would take care to thwart serious threats to us from countries farther away. Right now, it doesn't look like the Americans are living up to their part of that unwritten understanding."

"Over the years, it's also become more complicated because the more distant threats are connected to the ones closer to us. Iran is in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and to some extent in Gaza, and the distinction between near and far has gotten complicated. Even when the distinctions were clearer, the Americans wouldn't always take it upon themselves to deal with distant threats to us. Israel was forced to destroy the Iraqi nuclear reactor on its own, because the Americans weren't taking care of it. Today, the most significant distant threat is Iran. The Americans argue that they are dealing with it and declaring that they won't accept a nuclear Iran, but it's not clear what that actually means," Kuperwasser says.

Q: Practically speaking, what can we expect from the US in the case of a war on multiple fronts?

"First, we need to depend on ourselves. And after we've said that, the US is our best friend when it comes to defense. They disappointed us when it came to the nuclear reactors in Syria and Iraq, and also when we were kept from carrying out an action that would have delayed Iran's missile project in the 1990s and a few other times. On the other hand, they helped us – if late – with weapons during the Yom Kippur War, and when they put Patriot missiles at our disposal during the Gulf War, and more.

"At the end of Trump's term, he transferred the military cooperation between Israel and the US – which used to fall under EUCOM – to CENTCOM. That means that now we're more integrated into the American plans in the Middle East, and through that can also cooperate with other armies in the pragmatic Arab states, like the [United Arab] Emirates and Saudi Arabia. That increases our forces to a certain extent."

Q: In light of this special relationship, will the US rely on us at a time of crisis?

"The US acts according to its own security and diplomatic needs, and to a certain extent, takes those of its allies or friends into account. It passed the military aid law and in 1999 made an agreement with us to found a strategic planning group. There are other good connections and understandings, but the truth is, even when it came to countries with which the US had actual pacts, when it didn't want to take action, it didn't. The latest example, of course, is Ukraine. The US and Britain signed the Budapest Memorandum in 1994 and committed to helping Ukraine if it were attacked in exchange for Ukraine giving up its stocks of nuclear weapons. But when that was tested, Ukraine was left on its own."

Q: So a military alliance with the US wouldn't guarantee us anything.

"On the whole, that's right. Trump and Netanyahu brought up the idea of an alliance like that two years ago – in my opinion, because they believed it would help them get elected. If it were to come to pass, the agreement would need to be worded in a manner that would be less binding for both sides, and would leave them room to act. I'm not sure that would be possible.

"The idea of a defense pact between Israel and the US has been raised in the past, and rejected because neither side wanted to take on undesirable commitments that would restrict their freedom of action or oblige them to take action in military contexts that they did not view as vital or justified.

"Beyond that, the sense was that defense and diplomatic cooperation between the two sides was already at a very high level, so any advantages of a defense alliance wouldn't justify the changes it would entail to our defense outlook. Today, given the positions of the current US administration, which are very far from the Israeli view, or that of the previous administration, especially on the Iranian issue – the possibility of a defense alliance is even less relevant."