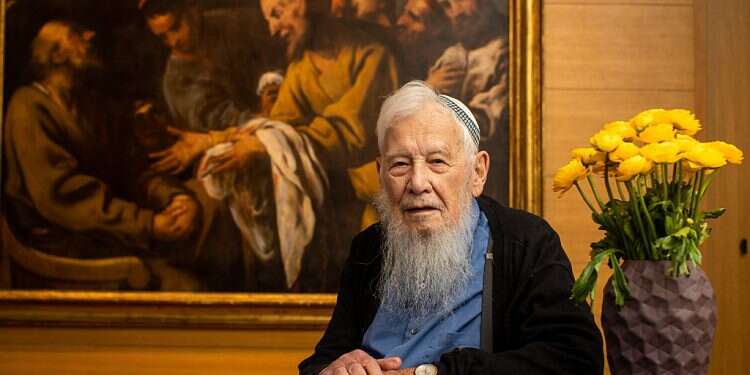

Getting an interview with Professor Yisrael Aumann required a long courtship. The 2005 Nobel Prize laureate in economics is an admired and important figure in the academic world. But the fact that he is deeply rooted in the religious Zionist world and joined the Likud party ranks at the age of 91 makes him a particularly fascinating interviewee.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

The professor does things at his own pace, and he wasn't easy to win over. In WhatsApp chats prior to our interview Aumann showed remarkable technological skills for someone who writes his academic works with an ink pen. Every time I tried to schedule an interview, he asked me to wait a bit until the timing was right. Before Rosh Hashanah, he told me he had rather harsh things to say, and it wasn't the right time to say them ahead of such an important and beautiful holiday.

"So we met on the morning of the eighth candle of Hanukkah and Aumann was more relaxed "because by the time the article goes to print Hannukah will already be behind us and we will be closer to the fast of the Tenth of Tevet, the date on which the siege of Jerusalem began, before the destruction of the temple that we cry and fast for. That is the time I have chosen to say the things I have to say.

Aumann lives in the Baka neighborhood of Jerusalem. A few years ago, he moved here with his wife from the Rehavia neighborhood where his daughter and her family lived in the apartment opposite. To get to his apartment, you have to go off the main Hebron Road to a small side alley and then go up on an outside elevator that isn't at all characteristic of the area, with its Jerusalem stone-clad exteriors. Inside the elevator, there is a plastic chair for anyone who wishes to sit down on the journey up. When I got to his floor, Aumann was waiting for me at the end of the corridor smiling.

He is alert and looks much younger than his age, He says his health is good and that he likes to eat watercress. As we sit down, I cannot but be in wonder of the huge oil paintings hanging on the walls of the living room depicting major biblical events. The most prominent of them is that of the sons of Jacob coming to their father with the bloodstained robe of their younger brother, Joseph. Jacob, and Miriam, Joseph's mother, gaze up toward the sky, refusing to look at the bloodstained robe.

"I'll call you Aviad, and you can call me Yisrael," says the professor as he walks over to the kitchen to prepare an Indonesian coffee. He likes coffee. "I think I must drink about 10 cups a day," he says. I tell him that coffee came fifth in a recent list of the healthiest drinks. "So perhaps I should start drinking more than 10 cups," he says with a giggle to his wife Batya as she appears from another room.

Batya, 93, seems a little curious about the interview. She stands within hearing distance of us. I take advantage of her presence to tell her about the film "The Woman" starring Glenn Close and Jonathan Pryce, which tells the story of a Nobel Prize winner in literature and his wife who for decades keep a secret - that it is she, not her husband, who wrote the literary works that gained him the biggest prize of all.

"That's not the case with us," Batya says with us. But the Aumann's story is no less worthy of a Hollywood movie. His first wife, Esther, with whom Aumann had five children, died in 1998. Seven years later, Aumann asked Esther's sister Batya, a social worker, for her hand in marriage, and she agreed.

She too has been blessed with sound health and memory. She has two children from her previous marriage, 10 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren. She was born in Berlin and came to Israel at the age of five. Her father was a doctor and for 20 years he was the director of the Shaarei Tzedek hospital. He combined medicine with politics as a member of the Agudat Yisrael party, but after the establishment of the state, he became a Religious Zionist. Both she and her husband consider themselves national religious. Together they have 21 grandchildren and 30 great-grandchildren, with another two on the way.

Aumann isn't wearing a mask face mask, but he does make sure to ask me whether I have been vaccinated three times. I respond affirmatively and he smiles.

Q: Let's talk about the coronavirus, especially about anti-vaxxers. As a man of science, what do you have to say to them? How do you see them?

"Primarily as people who are mad and dangerous. They speak all the time about individual liberties, yet somehow our society treats them with understanding. Individual liberties? What are they talking about? Can I drive at 150 kilometers an hour and endanger my surroundings and then laugh at everyone and say, 'What are you going to do about it?'"

"They are endangering others. You want to kill yourself? Fine, go ahead, even though here as well, all the anti-vaxxers eventually get infected, become ill and cost the health system a fortune – the health system has to treat them even though they have done everything they can to undermine it. But to endanger others? Whoever heard of such a thing? I'm absolutely livid about all this whole affair.

"People who refuse to be vaccinated should sit at home and ask their children or family to bring them food and take care of them. Take responsibility and save us from having to take responsibility for you. This is unparalleled anarchy."

Q: You said earlier that you chose to speak close to the fast of the Tenth of Tevet. Are you hinting that we live in a period that requires fasting and tears?

"What I want to say is that I am not envious of the young generation, and I say this about my children as well who are more or less your age. I am not envious of you, or my grandchildren or great-grandchildren. I see dark clouds and darkening skies on the horizon.

"I see what is happening in the world when it comes to antisemitism. It marches hand in hand with being anti-Israel, and to my great sorrow, it is spreading within streams that are considered the bon ton of global society. There was always antisemitism of the extreme Right in the world. But the extreme Right doesn't lead the world and doesn't set the tone. Those who really have influence are the progressives and the moderate Left in America and Europe

"I can see very strong antisemitism and anti-Israel sentiment, and it's beginning to be 'okay.' That worries me because I see it in almost all the newspapers in the United States, including in The New York Times, which is a very important and influential paper. I read texts by Peter Beinart in the Times and I am shocked. He is radically anti-Israel.

"It's the same at the universities. I am a graduate of City College in New York. In my time 90 percent of the students were Jewish. Today, it hosts BDS lectures and a group of professors denounced Israel, and the students at the law school denounced Israel. It's completely mainstream to attack us. At Duke University, a group of pro-Israel students asked to be accepted to the student organization and was refused.

"What I'm worried about is the changing tone of important opinion shapers, not the radicals. They are the generation of the future, not marginal neo-Nazi groups. Look at Bernie Sanders, a Jew who was a candidate for the presidency. I don't want to think what would have happened if he had won and become president. He is a typical anti-Israel Jew."

Q: But we aren't anywhere near the situation of 1930s style antisemitism in Europe that went on to become the Holocaust. We have a strong Jewish state.

"I'm not looking at another holocaust, but we have gone back 100 years to the beginning of the 1920s. Things are more difficult today in the world for Israel and for Jews. I suggest you look at an essay by Mark Twain in which he talks about antisemitic legislation passed in the Austrian Parliament at the end of the 19th century. Twain was pro-Jewish and claimed that that the root cause of antisemitism was economic – people were afraid of losing their livelihood [to the Jews]"

Q: On the other hand, for decades, Israel suffered from a particularly hostile attitude from leading European countries – the United Kingdom, France, the Soviet bloc – and that has changed completely. We have opened doors in Paris and London; Angela Merkel was a great friend.

"You're right, there are also positive changes. But my biggest concern is regarding the young generation, the leadership in 20-30 years from now, that is receiving anti-Israel indoctrination."

Q: Has anyone in America asked for your help?

"Jewish professors have approached me and I sent them a video in which I respond to accusations against Israel. We are spoken of as an apartheid state and I explain that what is happening here is nowhere close to apartheid. On the contrary. Do you remember what happened here last May, when there were disturbances across Israel? Jews were afraid to go into Arab neighborhoods, but Arabs weren't afraid to go into Jewish neighborhoods, and many in fact live in Jewish neighborhoods."

Q: But there were cases in which Jews lynched Arabs.

"True, but they were very few. What about the lynch in Ramallah? Jews entered Ramallah by mistake. Why does it have to end in a lynch?"

Aumann was born in Frankfurt in June 1930 to Miriam and Shlomo. His father was the biggest textile trader in the town. Three months before Kristallnacht in 1938, his parents read the map packed their bags, and moved to the United States.

Before the establishment of the State of Israel, Aumann's family belonged to an ultra-Orthodox anti- Zionist stream. "Their approach stemmed from the fact that the secular were Zionists and there was a need for a debate. The ultra-Orthodox back then were modern in their look and worked for a living. It was only after the Second World War when talk began of a Jewish state in the land of Israel, that my family became Zionist."

After graduating from City College, Aumann went to university, did a doctorate at MIT, and a post-doctorate at Princeton. He received an offer from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and from Bell Labs in New Jersey where the radio was invented and which had produced several Nobel Prize winners. His choice was between a comfortable life in America, near to home, or going to Israel.

His eldest brother, Moshe, had made Aliyah to Israel in 1950 and went on to a successful career in the Foreign Office. Aumann landed in Israel with his first wife, Esther, in the middle of the Sinai Campaign. They made the journey by taxi from what was then Lod Airport (in 1973 it was renamed Ben Gurion Airport) to Jerusalem in complete darkness because a blackout had been imposed due to fear of an Egyptian bombardment. Aumann's father had died in the United States two years earlier, and his mother came to Israel the following year in 1957.

Yisrael Aumann had five children but only four remain: Tamar, who works in high tech; Yonatan, a professor of computer science; Miriam, an educator; and Noga, a psychologist. His eldest son Shlomo was killed in the First Lebanon War in 1982. "I ask that we call it the Peace for Galilee War," says Aumann.

"It was on the eastern front. Shlomo served as a gunner in the tank corps and his tank took a direct hit from a Syrian ambush. I was told that Shlomo died on the spot. The tank commander was also killed. The only person to survive from his crew was the loader who jumped out and managed to escape.

"Shlomo was a law student at the Hebrew University. His wife, Shlomit, remains like a daughter to me to this day. She remarried her children and had children, who are like my grandchildren. She stepped into Shlomo's shoes and works as a lawyer."

Aumann stares at his watch, and I get the feeling that he has allocated a set time for the interview, but I don't know how much time he has put aside. Later in the day, he has to go out to the university. I ask him if he is going by bus, and he answers: "I drive my car, a 2018 Subaru Forester. There's no problem. Two years ago, I drove from Jerusalem to a hotel in Zichron Yaakov.

"From my apartment, it takes me about 15 minutes to get to the university in Givat Ram, to the Center for the Study of Rationality, of which I was one of the founders. From time to time, I give the occasional lecture at a seminar. The last time I taught a course with lectures was in 2013."

Aumann says that he likes to hike in nature and that he also likes to study Gemara. Until a few years ago he would go skiing once a year for a two-to-three-week holiday. He loves France and would like to spend a weekend in the Loire Valley. I ask him where he would still like to visit and he surprises me by answering Ras Mohamed in southern Sinai. "I was there about 50 years ago. It's a beautiful place that I would like to return to."

I ask Aumann about the most recent terrorist attack in Jerusalem. He wasn't aware of the details because he hardly watches television unless there's a major event. Batya, who watches the screen a little more, updates him on the important things, "mostly political, or when the prime minister speaks." She watches the news on Kan 11 and sometimes on Channel 12.

The professor gets annoyed with me when I ask his opinion of the state of Israel's students in mathematics and sciences.

"People think that if I am a Nobel Prize Laureate in economics, I can tell them whether I'm worried or not about the situation and about how well Israeli students are doing in mathematics. So, I give my regular answer, based on what I see in my private surroundings – my grandchildren and great-grandchildren, I see that my descendants are doing okay." Batya, who throughout the interview has mostly listened, breaks her silence for a moment to interrupt and says, "his grandchildren have very good genes and they are excellent students."

On the living room floor, there is a big colorful sign, which Aumann's great-grandchildren made when he won the prize. The sign read; "For I will bless thee, and multiply thy seed as the stars of heaven. With love. Your great-grandchildren."

Aumann won the Nobel Prize in 2005 together with Professor Thomas Schelling. from Maryland University for "having enhanced our understanding of conflict and cooperation through game-theory analysis,". He was in his room at the university when the announcement came through from the Prize Committee in Stockholm.

"I was in the middle of writing a scientific mail when I was told that an announcement would be made to the media in about 20 minutes. I was happy of course, but I also knew I wouldn't be able to be involved in science for a good few months. So I shut the door from the inside, finished my mail, and sent it."

Q: You spoke about the threat of antisemitism, and I would like to talk to you about the Iranian threat Do you see it as an existential threat to Israel?

"I don't know if it's an existential threat. Was there an existential threat in the Cold War? Because if there was back then, such a threat exists today.

"There was a time many years ago when it would have been possible to bomb Iran's nuclear facilities. That is what I have understood. It would have been possible to do what Menachem Begin did when he bombed the Iraqi reactor in 1981. And what Ehud Olmert did in Syria in 2007. It was possible to bomb Iran during Netanyahu's tenure but he didn't act. I don't know what considerations and constraints he had at the time. But the bottom line is, Netanyahu didn't make a move. It could well be that reality didn't allow for an operation.

"Obviously, we as laymen don't ever know all the details. But all I am saying is the fact is that Netanyahu was the prime minister at the time."

Q: When you came to Israel, David Ben Gurion was the prime minister, so you have known all of Israel's prime ministers. Who impressed you the most?

"That's a little like if you were to ask me about my children. I had five children, and now I have four, and you are asking me to tell you who I love the most. Thank God I also have 16 students who I mentored for their doctorates and sometimes people ask me, which of them was the best. Or which grandchild or great-grandchild I love the most. Each one of them is a whole world; what will I get out of it If I give them grades?

Q: Who was Ben Gurion for you?

"Ben Gurion was Israel's George Washington. There are many things to be said in his favor. He was a great leader who took an enormous decision to establish the state in very difficult conditions, despite strong domestic opposition, which was convinced that he was wrong. And he did make mistakes."

Q: Such as?

"I talk a lot about post-Zionism. People think that Peace Now was established in 1978. But it was established a lot earlier in the 1920s with Brit Shalom, and Rabbi Judah Magnes and his gang [Magnes was a reform rabbi and the first president of the Hebrew University] My mother's aunt, Hannah Judith Landau was part of that group. They liked the British and the Arabs and they were against the establishment of the state.

"People approached Ben Gurion and asked him, 'What are you going to do about the people that run the university and talk like that?' He replied, 'Let them talk as they wish, and I'll do what I wish. So he did what he wanted. But his dismissal of them was damaging. He needed to get other forces in education to come out against them."

Q: Let's talk about Menachem Begin.

"Begin was excellent, but he too wasn't devoid of errors. I met him after the Sabra and Shatila massacre in 1982. I told him that I support him, but that he needs to go to elections to get the backing of the people for this war.

"Begin's biggest error was that he was too much of a gentleman and brought [Supreme Court President] Aharon Barak upon us. Begin didn't fill the civil service with his people like Mapai did.

Q: But one of Begin's most famous statements, one that he was very proud of, was: 'There are judges in Jerusalem.'

"I disagree with him. The catastrophic changes in the legal system began with Aharon Barak who said that everything is justiciable. Instead of enforcing laws, we have reached a state where judges are above the Knesset. They express their personal opinion and make it the law of the land. Barak instituted a judicial revolution and the Knesset is no longer the body that creates the law.

"Look what happened with the Nation-State Law. The High Court decided that it was constitutional. That sounds good, but it isn't really because in the same measure it could have decided that it wasn't constitutional. The High Court has retained for itself the right and the capability to annul basic laws.

"It is scandalous that three Supreme Court justices sit on the Judicial Selection Committee and rule who will be appointed to the Supreme Court. I wouldn't give them three seats; I wouldn't even give them one. It is only here and in India that judges are involved in deciding who sits on the Supreme Court, and thus they perpetuate the ruling line of thought."

Q: Let's talk about Yitzhak Rabin

Aumann pauses for a few minutes, slipping deep inside himself, concentrating his focus on an imaginary figure standing before him, and finally says: "I don't know. He was a very complex figure, and I prefer not to talk about him."

Q: Let's talk about Benjamin Netanyahu. What in your opinion was Netanyahu's most significant contribution?

"He was most certainly a great statesman. He forged significant ties with states and built an important coalition against Iran. He is a magician in his ability to work behind the scenes, even though there was quite a lot of talk on the outside. He also acted extraordinarily and showed leadership when it came to the coronavirus pandemic and getting vaccinations from Pfizer. Absolutely.

"He did a lot for the country and I admire him. I really, really admire him. But there is also a problem with Netanyahu. He missed opportunities. He missed the opportunity during the presidency of Donald Trump to move forward with annexation. There was an opportunity to act, just as Begin decided to strike in Iraq. It's true that I don't know all the details, but in leadership, you must sometimes take decisions alone and cut yourself off from all the noise and pressure around you. The Americans didn't always agree with us, but sometimes they hinted that we should do what we think needs doing.

"Netanyahu didn't move to bomb Iran when it was possible. He didn't move to annex Judea and Samaria. I met Netanyahu several times – more than I met any other prime minister. I said to him, Mr. Prime Minister, make a move! I based that on the fact that the Trump administration said several times, 'Kids, you need to make a move, don't ask us.' Netanyahu hesitated. He had a problem with decisions that change reality."

Netanyahu displayed shades of greatness in his role, with the exception of taking advantage of opportunities. Previous prime ministers also worked under pressures and constraints, but they made their move nevertheless. Begin annexed the Golan Heights and we have already spoken about what he and Olmert did to nuclear reactors."

Q: Perhaps it's to Netanyahu's credit that he didn't rush to take risks.

"What about Ben Gurion? Was it clear in 1948 what kind of state we would have here? The Arabs rose up against us, but Ben Gurion took the decision and went with it all the way."

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

"Netanyahu appeared before Congress with great talent and spoke out against Obama's policy. But to appear in Congress is not like enacting Israeli law on the ground. Now people are denouncing Prime Minister Bennett because he isn't allowing construction in Area C and because we have a problem of governability over the Bedouins in the Negev. That makes me laugh because Bennett has only been in the role for six months. All these problems are the result of policy that existed throughout the Netanyahu years. I don't understand how people can make claims against Bennett. I'm not necessarily one of his biggest fans but you have to be fair toward him. The problems were here before he was."

Q: If Netanyahu were to have consulted with you about how to handle his trial, what would you have advised him?

"I don't know what I would have advised him on the legal level, but Netanyahu should have stepped down from the political map, and not because he wasn't a good prime minister. The problem is that just over half of the nation didn't want him and he should have moved aside to allow somebody perhaps less talented than him to form a right-wing government.

"Now what has happened? We have a sort of unity government, and Netanyahu despite all his abilities, isn't prime minister anymore. In the end, we have a democracy here and the majority, even if it's only a small majority didn't want Netanyahu. Once time, and then another, and then another. Netanyahu too beat [Shimon] Peres in 1996 with a very small majority. But a majority is a majority nevertheless."

Q: Let's talk about game theory, the field in which you are an expert. How does game theory impact politics?

"Let's say there are three players that represent three parties in a parliament with 100 seats. One party has 49 seats, another party has 49 seats, and a third party has two seats. There is an index in game theory, which is called the Shapley Value and I would like to ask you, 'what power does each of those three parties hold?

Q: I'm afraid to make a mistake. Go ahead and answer for me.

They each have equal power: One third, one-third, and one-third. The fact that Naftali Bennett has six seats is irrelevant. And that's what good old game theory says."