The Israel Police and the Shin Bet security agency are still exercising caution and are not calling the last eight stabbing and shooting attacks in Jerusalem – and dozens of other attacks and attempted attacks nationwide in the past 10 weeks – a wave of terrorism. The Israeli public, on the other hand, has been forced to acknowledge that "shahada" – a martyr's death – is seeing a renaissance in Palestinian society.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

The many terrorist attacks have led to greater focus on the "shahid" and their qualities in Palestinian media and social media. This focus never shifted, but is now taking up more space. The relevant Quran quote is also being thrown around frequently: "And do not say about those who are killed in the way of Allah, 'They are dead.' Rather, they are alive, with their lord, and they have provision."

Now Israel Hayom is exposing the wills of the terrorists, both those who were killed during the attacks and those who lived through them, and their motives. The wills teach us about the harsh terminology that arises from their last letters and social media posts – what they leave behind.

Former mufti of Jerusalem Sheikh Ikrama Sabri explained during the Second Intifada that "the Muslim loves death and martyrdom like the Jews love life." The wills of the latest two shahids who, unfortunately, managed to carry out their plans, illustrate Sabri's remark. They both wanted to die. Mohammed Shawkat Salima, who last Saturday fell on Haredi youth Avraham Elmaliach near Damascus Gate in the Old City of Jerusalem and wounded him badly before he was fatally shot by security forces, posted on his old Facebook page a post in which he defined himself as "a martyr on the waiting list."

"May Allah soon bring me to him," Salima wrote alongside a picture of another Palestinian, Sab Abu Abid, who was killed in clashes with the IDF in 2017.

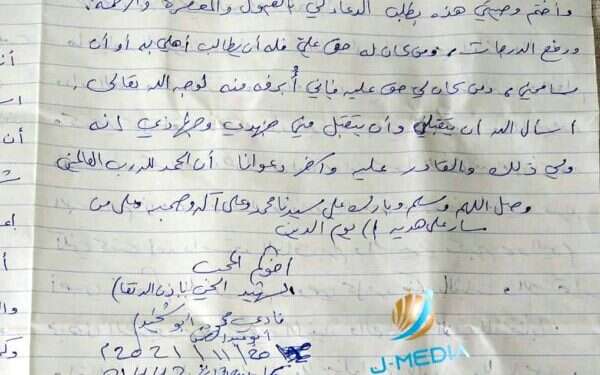

Fadi Abu Shkhaydam, who murdered Eliyahu Kay near the Western Wall, was also fatally shot. Before leaving to carry out his planned attack, he left a much more detailed will than Salima's, in which he claimed that "after years of work, study, and teaching, there is no choice but to let the ship said on our blood and serve as a practical example in the field of jihad."

Until recently, Abu Shkhaydam, a member of Hamas, had a working relationship with high-ranking members of the Muslim Waqf on the Temple Mount and only four months ago finished running a course offered by the Waqf titled "The Battalion of Resilience and Ribat."

He also took care to integrate "ribat" – an Islamic term that describes taking one's place at the front of a holy war against infidels – in his will, in which he wrote, "The best path for us in light of the abuse of our mosque [Al-Aqsa Mosque – N.S.] is to redeem it with our blood. We have no honorable life so long as our mosque undergoes one failure after another and so long as the assaults against it increase. Therefore, prepare yourselves for ribat, for jihad, for sacrifice, and to give your life and throw off the bonds of this world."

The written statements the killer left behind are unusual when compared to the wills of other murderers of his profile, because Abu Shkhaydam went beyond background and explanation for his planned action and actually instructed the hundreds of pupils he left behind to prepare themselves for similar acts in the future.

Half leave wills

Nor are Abu Shkhaydam and Salima alone. A look through dozens of wills reveals not only the terrorists' motives, but also their need to share their "legacies" with large audiences and win legitimacy for their deeds.

For Israel's security forces, the wills are a treasure trove that enables them to heighten the precision of the system that tracks hundreds of thousands of internet users and social media participants each day, hoping to thwart similar attacks. Authorities think that hundreds of attacks have been prevented this way.

The scope of the tracking and location work is enormous, especially at times of tension around the Temple Mount. In a single day after the shooting attack on the Mount itself in July 2017, over 500,000 posts from the PA territories and the Arab world went up discussing the situation on the Mount. Many intended or directly called for terrorist attacks.

The wills, however, often tell a story that is not religious or nationalist, but one of personal distress that led the attacker to carry out their plan. Mohammad Younis, who last week ran his car into a security guard at the Te'enim checkpoint, is believed to have argued with his father before taking his car without permission and deciding to become a martyr.

Other times, the motive is revenge or identification with other shahids, what the Shin Bet calls "copycat attacks" or "infection." In the case of Tharwat Ibrahim Salman Al-Shawari, 72, a mother of five who tried to run down soldiers near Halhul, the attacker had a sense that her death was approaching. She had told her relatives that if she was going to die, it would be better to do so as a shahid rather than "in bed," as she called it.

Some 50% of terrorists who carried out attacks or attempted to in the last few years left behind some kind of will. The most common motive documented in the wills is the situation of Al-Aqsa Mosque and the desire to defend it from "Jewish invasion," a reference to Jewish visits to the Mount. In Palestinian society, the Al-Aqsa shahids are considered the elite, celebrities in every sense, and guarantee themselves a place of honor in the Palestinian pantheon of martyrs. Their wills are according popular.

This is the kind of fame that came to Abu Shkhaydam, who wrote to his "brothers and comrades in dawa and Islamic activity" that "our blessed words and dawa, with which we have been busy since we were young, demand that we sacrifice and give our lives so that our words will not stay dead or without life." (Translation courtesy of MEMRI).

Abu Shkhaydam even appealed directly to his students: "In every meeting I was sorry [to hear] that someone had beat me to Paradise by attacking [the enemy]. I would tell you stories about them, from friends of the Prophet to the lions of Islam of our time. Long live Allah. I never ceased to weep when I would tell you about them, but I would prepare myself and prepare to join them and follow their path … I command every one of you to adhere to this path."

One of the "lions of Islam" about whom he taught his students was Mesbah Abu Sabih, who left behind a chilling will of his own. Abu Sabih, known to his admirers as the "lion of Al-Quds," murdered Levana Malichi and Yosef Kirma in a shooting attack at the light train station on Bar Lev Blvd. in Jerusalem in October 2016.

Abu Sabih was also a member of Hamas. He also wanted to prevent Jews from visiting the Temple Mount. Like Abu Shkhaydam, he taught the Quran at a mosque and the writings he left behind before he was fatally shot while carrying out his attack predicted what was to come, but were not identified in time.

'A revolution has begun in Jerusalem'

Abu Sabih, whom Abu Shkhaydam admired, admitted he envied shahids and wanted to be like them. Among other things, he wrote that "Al-Aqsa Mosque is awash in blood," "was burned every day for 47 years and awaits someone who will put it out … do not abandon Al-Aqsa Mosque." In his will, he pleaded, "On Judgment Day, we will be asked what we did for Al-Aqsa Mosque to keep it part of the faith of every Muslim in the world."

Without Al-Aqsa, he warned, "There will be blood. There are men who will redeem Al-Aqsa with their blood. Jerusalem sits on the mouth of a volcano that is about to erupt. Al-Aqsa Mosque is closed and the murderers of children invade it every day." But, he wrote, "In Jerusalem, a revolution has started that is not a revolution of rocks alone."

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

Abu Sabih, who was a violent type with a criminal past, and Abu Shkhaydam, supposedly more learned and gentle, wrote nearly identical things. So did Mohammed Tarayreh, 19, who murdered Hillel Yaffa Ariel, 13, while she was sleeping in her bed in her home in Kiryat Arba in June 2016.

Omar Al-Abed, a resident of Kobar who stabbed three members of the Salomon family as they were gathered around the Shabbat table in their home in Halmish, left a "last will and testament" on Facebook an hour and 40 minutes before leaving to kill. His writings also dealt with the "bitter fate of Al-Aqsa."

"The mosque is being defiled and we sleep," Al-Abed scolded. "It is a disgrace for us to sit and do nothing. You, who pull out guns only at weddings and celebrations, are you not ashamed of yourselves? … All I have is a honed knife and it is answering the call of Al-Aqsa. I am going to Paradise, my home is there. I want nothing beyond that. Allah will judge whoever does not carry out my will. Put a band of Al-Qassem around my head and on my chest, a picture of Abu Amar [Yasser Arafat]. I will take them to the grave with me."

'The noose is around my neck'

But it's not all about Al-Aqsa. Ibrahim Halas, who in April 2020 ran down a police officer at a checkpoint in Abu Dis and was fatally shot at the scene, connected his act to criminal trouble, writing, "They set the entire world against me, they ruined my life. The noose is already around my neck. From the time I was young, I drank alcohol and used drugs, but I am an honest and fair person and want to divorce my wife for these reasons, which have brought me to the edge."

Nimer Mahmoud Jamal, who was 37 when he murdered three Israelis on Har Adar in September 2017, also did so because of personal problems. He had a long string of violent criminal offense, mostly domestic violence, and in his will he told his wife that she should not be troubled because of his actions. "You have nothing to do with what I am about to carry out. I was a bad husband and a bad father and you were a good wife and a caring mother. I tried to mend my ways, but I never could. You deserve a better life than the life you had with me."

There are also attackers inspired by a desire to mimic or get revenge. Ayman Kurd, 20, who stabbed two police officers near Damascus Gate after his cousin Ramzi died in a shooting in Hebron, wrote to his mother: "Be sure that I did not do this because of anyone, but of my own will. I thought about it even before my 'brother' Ramzi died a martyr's death … Bury me in the shahids' graveyard near my brother Ramzi." Kurd even asked that his death be celebrated: "I want them to have a party for me."

Longing to die

Abada Abu Ras, the son of a senior Hamas official who was deported to London in the early 1990s, was responsible for a terrorist stabbing in Givat Zeev in January 2016. Two weeks earlier he had written: "I long for an event in which I will lose my life." Abu Ras posted a picture of his inspiration – Mohand Halabi, who murdered Nechemia Lavi and Aharon Benita three months earlier.

Fuad Abu Rajab a-Tamimi from Issawiya in east Jerusalem, who opened fire on two police officers and was killed at the scene, left an explanation that he wanted to become a martyr. "My death was to sanctify and glorify Allah… Don't spread hatred in the hearts of my brothers after my death. Let them discover the religion and their own path, so they can die for the purpose of being a shahid and not as revenge."

Qutaiba Zahran, 17, from the Tulkarem region, who stabbed a Border Police officer near Tapuah Junction and was shot and killed on the spot, wrote a long post on Facebook titled "The will of a shahid," in which he bid farewell to his family and explained that the attack he was about to perpetrate was to avenge the blood of "Palestine's shahids."

The many wills and posts that the attackers prepare show that most assume they will die trying to carry out their plans. The catchy message that Yasser Arafat made popular years ago, "Millions of shahids are marching toward Jerusalem," is being voiced again now. If this is the case, it's hard to discuss deterrence, and what's more, Palestinian society for the most part embraces the martyrs and even praises them. In a reality like this, security forces' main focus is on preventing attacks through human intelligence as well as electronic means, and by being on the alert – as we have seen at Damascus Gate.