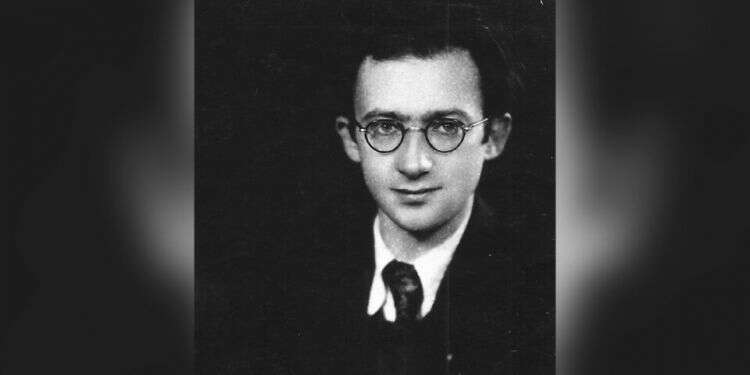

The Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg sometimes called him Avram or Avrum Gratzbitz. Others used Avrasha, or even Avrishinka. In short, he was Sutskever and that's that. To write about Avraham Sutskever is a bit like bringing your fingers closer to the fire. Would it be an exaggeration to say that he was the greatest poet who lived here in Israel?

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

At any rate, he did not pause but pushed on ahead, as we can learn from the notes he made in his diary about Berlin, when he was there on his way to Nuremburg in February 1946, in order to testify in the biggest trial of Nazi criminals. "The city center is a ruin. The American and British pilots were reliable," he wrote. "The paved streets remain almost completely intact, while the white buildings have become sleepy piles of rubble on the roadside."

He didn't make do with enthusiasm for the destroyed Berlin, which provoked great hatred in him: "Berlin; they made a pleasant ruin out of you. But it's not enough. May you be cursed forever and ever and never rise again." The Germans, in his eyes, were "very talented idiots."

"Alexanderplatz still retains something of its former splendor, and it looks like an old and decaying prostitute who insists on looking young."

Previously, only an Israeli reader could enjoy this. Now that a portion of Sutskever's letters have been published for the first time in English (in the United States and Canada), there can be a new perspective on the writer, mainly as an author of memories. The diary he wrote about the Vilna Ghetto was published a decade ago by Am Oved, with an introduction by Justin Cami and Avraham Noverstern. The new book in English includes other anthologies that weren't included in the Hebrew edition.

These anthologies include Sutskever's testimony at Nuremburg, and everything he wrote in his diary about his testimony and his journey to the city, as well as three brilliant profiles of the writer Ilya Ehrenburg, the actor Solomon Mikhoels, and the poet Peretz Markish. The profiles appeared in Yiddish in the 1960s in Di Goldene Keyt ('The Golden Chain), a journal edited by Sutskever, in Tel Aviv, and afterward were reprinted in a publication by Magnes Press in 1993.

One can imagine the chain of these artists over the years like whispering embers in Israeli society. Ilya Ehrenburg was contemptible in the eyes of Ben-Gurion, to say the least. One can also crudely relate this to Ehrenburg's connection with Stalin. However, when one goes into the details, as Sutskever does, a very different and far more humane figure emerges. While reading, one realizes the diabolical entanglement that the major Jewish artists were forced to live in the heart of the Stalinist regime in the 1940s.

An inferno of informing and executions

The book's editor, Smith College's Professor Justin Carmi, told me that the depictions of the period from 1944 to the middle of 1946 in Moscow are one of the most fascinating parts to come out of the book, and that Sutskever was there in order to report on them. The 1940s include the Holocaust, the German destruction of the Vilna Ghetto, and afterward Sutskever as a partisan poet in the Narotz Forests.

Towards the end of the decade, in 1948, the year of Israel's independence, Mikhoels was murdered by Stalin's agents. Peretz Markish, who according to Sutskever's testimony was already targeted for Stalinist assassination in 1945, was executed at the end of the horrific 'Night of the Murdered Poets' in the Soviet Union in August 1952. But how many Israeli schools devote any time, with all the Mahmoud Darwish and the Gush Etzion poets, to the physical extermination of Jewish artists in the Soviet Union?

The fact that Ehrenburg and Sutskever survived the Stalinist inferno casts a shadow of suspicion on Ehrenburg because he was seemingly a member of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee and he seems to have been the only member to have survived, and on Sutskever because of his friendship with Ehrenburg.

Unless there is other evidence, though, we need to accept the testimony of Sutskever regarding Ehrenburg, and he even notes at the end of the wonderful section about him that over the years he researched the subject: did Ehrenburg expose or denunciate or sign some sort of document that implicated him in the executions of the authors and the poets? He states that he didn't find any evidence or proof. However, the evidence and the circumstances regarding the personality of Ehrenburg, and the inferno of informing and executions, both during and after the war, are enough to explain the man and his conduct and are sufficient to exonerate him.

Ehrenburg was an international figure. Stalin gave him his patronage, as he did to Sutskever. This patronage was because Ehrenburg was a strategic asset inside the Soviet Union and in the international arena. It's almost possible to compare his position to that of the Marshal of the Soviet Union, Georgy Zhukov. At a certain stage, Stalin and his entourage excommunicated both of them, but because of their independent status, they didn't have the power to execute them. From this, it's extremely clear that Ehrenburg didn't need to denounce or to inform his friends in order to survive.

Territory? Only the Land of Israel

The 'Black Book' initiative to document the Holocaust is to Ehrenburg's credit. He gathered every piece of material about the Holocaust, while the Americans and the British were doing everything they could to give the Germans a free hand to exterminate the Jews, and in so doing to solve the problem of Zionism and immigration. Before his testimony at Nuremburg, the Soviet legal officers made him understand that he was testifying as a Jew about the suffering of his people. This hints that the Soviet authorities already saw before their eyes in 1946 a national solution for the Jews (a Jewish state). According to every testimony brought by Sutskever, this spirit already dominated from 1944.

Sustskever writes that he had an obsessive fantasy, that he would enter the court with the pistol from his days as a partisan, with six bullets, would get to within one meter of the accused, and would shoot Goring. He discussed this, being careful to present the scenario as a hypothetical one, with Ehrenburg, who pretended not to realize that it was Sutskever himself [offering to do the deed] and proceeded to expand on what the political results of such an assassination would be. It was enough to remove the wind from the sails of revenge and hatred from the poet.

Ehrenburg, who covered parts of the trial as a journalist, once found one of the German lawyers and asked him: "Tell me, in Germany, are you still greeting each other with Heil Hitler?" His answer: "No, because they forbade us from doing it."

"I knew him during the 'good years,' when his words were like burning foxes running through the battlefields, igniting hatred and demanding revenge against the Germans," Sutskever writes.

Ehrenburg made possible Sutskever's first appearance in Moscow, on April 2, 1944, immediately after he was evacuated on a flight from the Narotz Forest. In the eyes of Stalin and the entire cultural establishment of the Soviet Union, he described the war of "hundreds of fighting Jewish partisans – proud and courageous avengers of the blood of their brothers…I call on you, Jews of the world, fight and avenge their deaths." All of the speakers in the Hall of Columns dedicated their speeches to Stalin; Sutskever didn't mention him at all.

Towards the end of the war, the journalist Shakne Epstein and the actor Mikhoels approached Stalin's deputy foreign minister, Maxim Litvinov, and demanded that at the peace conference – which they thought would take place just like after World War I – Crimea would be made into a "Jewish center." Litvinov replied: "Forget about it. If you want territory, isn't the Land of Israel the answer? It would also receive the support of Jews around the world." According to Sutskever, Ehrenburg liked this position and emphasized that if the territory was on the cards, then it had to be the Land of Israel.

An award means incarceration

There is a debate regarding when Stalin became a "Zionist," i.e. adopted the solution of a Jewish state. Some think it was when Andrei Gromyko, who was then Soviet Permanent Representative to the United Nations, gave a speech at the UN in June 1947. The testimony of Sutskever, from the heart of Stalinist territory, proves that the Soviet trend towards a Jewish state – rather than support of Zionism – began at the height of the Second World War.

Solomon Mikhoels, the legendary theater actor and director, was one of the people who pushed the Soviets to save Sutskever and his wife from the forests. He became noted, among other things, for his [1935] role as King Lear on the Yiddish Stage; in such a manner, King Lear became fused in Sutskever's mind with the horrific 1948 death suffered by Mikhoels [by many accounts an assassination later made to look like a hit-and-run]: "Every time I think about Mikhoels I see him in my imagination in the same scene: in the field, at night, in the heart of the storm, his hand manically striking his forehead. Such was the fate of this great artist, [who led] a kingdom which was betrayed, when on January 13th 1948 the dark Moscow-born specters sought him out in Minsk and glistened with his red blood."

Ultimately, one can connect the murders of the intellectuals, members of the Anti-Fascist Committee, to the same logic that drove Stalin to murder those who fought in the Spanish Civil War. In the mind of the paranoid dictator, anyone who served a certain period outside the Soviet Union became an agent of the "enemy," no matter who they were. This included members of the committee who were in contact with figures in the West, and especially in the United States, and people like Mikhoels who had also spent time there. The murder of Mikhoels gave a green light to a wave of antisemitism, precisely at a time when the Soviet Union supported the Jewish struggle for independence - his Jewish writer friends, some of them from the Anti-Fascist Committee, were murdered in 1952.

In his essay on Peretz Markish, Sutskever describes a frightening event that took place in the summer of 1945. It becomes clear that Stalin and Zhadnov's cultural committee were already planning to execute him. Sutskever describes a warped scene that took place with an apparatchik from the Ministry of Information. It began with a "happy announcement" that they wanted to award him the Stalin Prize. From Sutskever's perspective, this meant a kind of jailing. If he received the award, then he wouldn't be able to leave the Soviet Union anymore.

When he was about to leave, the figure suddenly changed the subject. What was his opinion about Peretz Markish? Sutskever told him that he was one of the most revolutionary Yiddish poets. The functionary, meanwhile, was accusing Markish of insulting the Red Army and had a copy of a poem by Markish accompanied by the opinion of his accuser, as well as the signatures of a number of intellectuals (who were known for denunciations). The meaning of this was liquidation.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

Sutskever defended Markish, and despite the threat he claimed that he couldn't succeed in finding any harm or insult to the Red Army in the poem. Next something happened that could have been lifted from the pages of a story by Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Sutskever was dying to see who the signatories were, but they were listed on the other side of the page; when he returned the document back to the minister, a gust of wind turned the page over and Sutskever quickly managed to identify two names. He didn't divulge the second name of the denunciators in his essay, since the same writer was himself executed in August 1952. Before leaving for Poland, from where he made his way via Paris to the Land of Israel, Sutsekver parted from Markish and told him what had happened. Markish survived another seven years on borrowed time.

The translator and editor of the book From the Vilna Ghetto to Nuremburg, Professor Justin Kami, said in an interview with the Jewish Ledger that "three things interested me [about Sutskever]. He starts out as a poet in the 1930s, so that from my perspective it challenges the myth of Yiddish as an old and dormant language. He represents a moment that in my next book I call When Yiddish was Young, a moment when it was a language in daily use, and was used by radicals, revolutionaries, and progressives – and of all the politics that existed in that same world."

Sutskever, Kami says, "was part of the world of modern Yiddish poetry, which spoke both to the Jewish reader and to the wider world. Afterward, when you pass to a different period, he is certainly close to being one of the three most important Yiddish poets, if not the most important of them. That's the period of the ghettoes and the Holocaust. He wrote throughout the war period, without a break, and his epic poems and works are classics. During that same period, he is only in his thirties, and so he gathers up his life and decides that the future of a Jewish author is in the Land of Israel…he wants to be surrounded by the Aleph-Bet of the Hebrew letters in the land of Hebrew-speakers."