Did the events that gave us the Hanukkah holiday 2,000 years ago shape Jewish religious culture as we know it today? Lessons about the history of the Jewish people in general and the Hanukkah events in particular tend to focus on the Hasmonean leadership and other notable figures of that era. But a new book based on archaeological findings attempts to portray the day-to-day lives of the regular people who lived at the time of the Second Temple and how the Maccabees' victory and the Hanukkah miracle influenced the Jewish population in the Land of Israel at that time.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

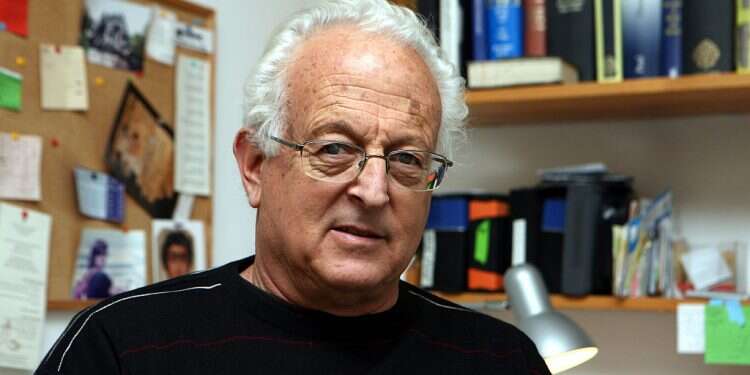

"I'm not a historian or a researcher of Jewish history. I examine [archaeological] finds and in this case, Jewish culture according to archaeological discoveries," says Professor Ronny Reich, a former lecturer at the University of Haifa and author of the new book Everyday Life: The daily life of the Jewish community in the Eretz Israel in the Late Second Temple Period in Light of Archaeological Finds (published by Pardes, Hebrew only).

According to Reich, the success of the Hasmonean revolt against the Seleucid rule – which happened mostly as guerilla warfare – poses a challenge for modern archaeologists. After the Maccabees wrested control of the land from the hands of the Greeks, many of the buildings that had been destroyed were rebuilt and it has been difficult to find evidence of them in archaeological excavations. However, Reich says that discoveries made in recent years have been more helpful in revealing how the priest Mattathias and his sons influenced Jews' lives in the period following the events that inspired Hanukkah.

The revolt against the Greeks began in 168 BCE and 16 years later resulted in the founding of the Hasmonean dynasty, which would go on to rule the land for close to 80 years. According to Reich, "When the Hasmonean dynasty rose to power, we see much stricter religious observance. In my opinion, this was the start of Jewish culture as we know it and had many expressions."

One example Reich cites is the mikveh, which he researched for his doctoral dissertation. "Maintaining purity as a religious rite, linked to entering the Temple and the Mount of Olives, starts in the time of the Hasmoneans. Jews, who needed places to purify themselves, built these sites. There are no archaeological remains that show that purification facilities, mikvehs, existed in earlier times."

Another possible indication of more stringent Jewish religious observance after the events of Hanukkah is the matter of pictures and sculpture, which could be a backlash to the Greeks' decrees about idolatry.

"In Jewish communities, there is almost no depiction of people or animals because of the Second Commandment, 'Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.' We don't see this in excavations of Jewish communities, in contrast to the non-Jewish communities discovered in the region," Reich says.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

Reich says that pilgrimage to the Temple also gained in popularity under the Hasmoneans. "The story of the defiling of the Temple and its rededication strengthened the subject of pilgrimage and the Temple as the Jewish people's only place of worship. This is unique to the Jewish religion. The Romans, when one temple got too crowded, simply built another one."

In his new book, Reich explains that increased emphasis on pilgrimage to the Temple can be seen in the large number of cooking vessels used by pilgrims found discarded on the outskirts of the city, as well as the large number of animal bones they threw away. "Not pig bones, of course," Reich stresses.

In another development under the Hasmoneans, import of wine produced by non-Jews was stopped, another indication of increasingly stringent adherence to Jewish law about the production and consumption of wine. "[Wine] imports ended. The drastic drop in appropriate jugs [found] is proof of this," Reich says.

History tells us that many Jews, prior to the events of Hanukkah, adopted Greek religious practices, and that the Hellenistic culture left its marks on the Jewish people. But when it comes to how, or if, that was expressed in the period following the Maccabees' victory, Reich says in his book, the question remains unanswered.

"In my opinion, the question of buildings that were used for leisure in the spirit of the Hellenistic culture remains unsolved. Activities that took place there in the Hellenistic world were far from the religious character of the Jewish population, and even opposed to it. It should be noted that currently, we know about them only from the letters of Joseph Ben Mattityahu [Josephus Flavius], and have not unearthed any real archaeological remnants of them," Reich says.