During Napoleon's failed campaign to conquer the Land of Israel in 1799, an impressive proclamation was issued from his general headquarters to the Jewish people, in which he declared his desire to establish a Jewish state in the Land of Israel. And lo it read: "Bonaparte Napoleon's statement to the legal heirs of the Land of Israel! Israelites, unique nation, whom, in thousands of years, lust of conquest and tyranny have been able to be deprived of their ancestral lands, but not of name and national existence! Arise then, with gladness, ye exiled! A war unexampled In the annals of history, waged in self-defense by a nation whose hereditary lands were regarded by its enemies as plunder to be divided, arbitrarily and at their convenience ... avenges its own shame … and also, the almost two-thousand-year-old ignominy put upon you ... and now it offers to you at this very time, and contrary to all expectations, Israel's patrimony.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

"Lawful heirs of the land, this great nation [France] calls out to you: herewith calls on you not indeed to conquer your patrimony; nay, only to take over that which has been conquered and, with that nation's warranty and support, to remain master of it to maintain it against all comers. Arise! Now is the moment, which may not return for thousands of years, to claim the restoration of civic rights among the population of the universe which had been shamefully withheld from you for thousands of years, your political existence as a nation among the nations, and the unlimited natural right to worship Jehovah in accordance with your faith, publicly and most probably forever..." (Merhavia, "Zionism: The Treasure of Political Certificates", pp. 17-15).

This impressive document and the rumors about it left a strong impression and inspired both the press in Europe and the Jews, many of whom joined the Napoleonic armies in its wake. For example, exactly one hundred years later, when Herzl turned to German Emperor Wilhelm II to support Zionism, he wrote to him: "What could not be fulfilled under the reign of Napoleon I, can be fulfilled by Wilhelm II."

Ideas for the renewal of the Jewish state made the rounds in Napoleon's circles even before he set out on the journey, and were proposed both by Jews and by Millinerianist Christians, but their meaning cannot be understood without first clarifying the roots of the Christian prophecy of the return of Jews to Zion. This is an idea, deeply rooted in the ancient Christian concept of the "millennium", which describes a period of a thousand years in which Jesus will rule after his second coming. Only afterwards will the war of Gog and Magog take place, the dead will live and the New Jerusalem will be founded. Belief in the millennium was already rooted in the early writings of Christianity, and diverse groups of Christians have been influenced by it in various ways throughout history.

Jews in the most literal way

Some Christians understood the significance of the millennium to require the return of the Jews to Zion, for their future sake and for the realization of the Christian prophecy. Some even tied this vision to a political-sovereign revival of the Jews. Author Barbara Tuchman, in her book "Bible and Sword", demonstrates the power of Millinerianist unrest in 17th-century Europe through the story of Sir Finch.

In 1621, Henry Finch, a legal officer of the King of England, wrote an essay in which he predicted that in the near future the Jews would return to establish their kingdom, which would function as a worldwide empire, and to which the other kingdoms would be subordinate. He was soon imprisoned by King James I, who disliked the idea of the potential violation of the absolute sovereignty of the English king.

One of the main reasons for this awakening was the return of Protestant Christianity to literal reading of the Hebrew Bible. In contrast to Catholic Christianity, which forbade the masses to read the Holy Scriptures on their own, the Protestants encouraged the masses to read the Bible regularly and without mediation, including the "Old Testament". Returning to the texts of the Bible was not a purely technical matter, and had very significant consequences. One of them concerned with understanding the future of the Jews. Classical Catholic reading used to read the verses of prophecy dealing with the return of the Jews to Zion at the time of redemption in an allegorical reading. This is why "Zion" was interpreted as the church's faith, and "Bnei Yisrael" (children of Israel) was interpreted as the church's believers, who are "the new Israel". However, when the Protestants re-read the Bible literally, the Millinerianist Messianic faith re-emerged with great power.

Thus, for example, Finch wrote: "Where Israel and Judah and Zion and Jerusalem are mentioned, the Holy Spirit does not mean a spiritual Israel ... but an Israel descended from Jacob ... We did not use the language of allegory in earthly images, but meant Jews in the most real and literal way."

From the 18th century onwards, a topical interpretation of current events in connection with the processes of Millinerianist redemption intensified in England and France. The French Revolution provoked tremendous Millinerianist unrest among vast populations of Christians, who saw it as the first step of a Messianic era. For many years, the Protestants saw the Catholic Church and the kings of France as an anti-Christ, meaning, a satanic factor that showed wickedness to the representative of the kingdom of heaven.

With the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the French Republic, the prophecies of the Millinerianists seemed to come true. Essays dealing with contemporary redemption became extremely common, and an important part of them was instilled with the hope of "paving the way for the return of the Jews and preparing mankind for greater blessings than ever before."

The destabilizing of the Pope's status by the Revolutionary Army following the conquest of Italy in 1796, and in particular Napoleon Bonaparte's campaign in Egypt and the Land of Israel (1798-1799), strongly confirmed the identification of the process and provoked sharp controversy in England over the subsequent stages of Jewish return. One British writer was certain, based on the verse in Isaiah (60:9) - "Surely the islands look to me; in the lead are the ships of Tarshish, bringing your children from afar", that this "does not so explicitly apply to any nation as to the British nation, which will probably be joined by the Dutch states".

In contrast, some apocalyptic thinkers were certain that France was destined from heaven to lead the Jews to their land. So much so that when Napoleon's army was preparing to invade Britain in the early 19th century, there were Englishmen who refused to take part in the war against the invading army, as they perceived it a sin to fight the divine army designed to redeem the people of Israel and return them to Zion.

At the same time, a large part of the population in France also interpreted the events of the revolution in relation to apocalyptic calculations and Millinerianist beliefs regarding the return of the Jews to Zion. As the historian Jonathan Frankel concluded ("The Damascus Affair", 1997, p. 287): "The French Revolution and Napoleonic wars once again transformed eschatology in general and restorationism in particular, from the esoteric pursuits that they had become in the 18th century into an issue of major popular concern."

Messianic-Christian beliefs that saw the establishment of the Jewish state as part of the Christian redemption continued to interest broad circles in Britain throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and even influenced British policy during this period, and at least indirectly, even the fate of Zionism and the establishment of the State of Israel.

'Unbeatable tenacity'

The important influence on England's foreign policy can be seen in the long and crucial reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901). The "Jewish Restoration" movement was established in London in the late 1830s and carried the banner of the return of the Jews to the Land of Israel in order to return their independent state to them. This was due to the vigorous activity of Lord Shaftesbury, an evangelical Anglican, who in those days dared to prophesy in unequivocal language: "Jerusalem will regain its place among the families of the Gentiles, and England will be the first kingdom to remove from it the burden of bondage."

A body called the "London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews" held rallies attended by thousands, even led by Queen Victoria herself, who was very close to these circles. Lively discussions took place regarding the stages of redemption of the Jews, the time when they would convert to Christianity, and the question of whether equal rights in Britain or the right to be elected to parliament promote the redemption of the Jews, or vice versa. Evidence of messianic unrest among the Jews themselves, for example around 1840, also greatly increased the hope for imminent redemption.

Throughout this decade, Lord Shaftesbury worked hard to promote Britain's hold on the Land of Israel, and in particular to prepare the path for it to become the patron for the return of the Jews. His closeness to Palmerston, the Foreign Secretary who later became Prime Minister, enabled him to have real influence on British policy regarding the future of the Land of Israel. Shaftesbury's continued activity pushed forward the appointment of a British Deputy Consul in Jerusalem in 1838, and with his direct encouragement his jurisdiction in Jerusalem and Palestine was defined as "within its ancient borders."

Shaftesbury interpreted the appointment as meaning that the deputy consul was "empowered to be what was the kingdom of King David and the 12 tribes". After his appointment he wrote enthusiastically about this step, in which he saw as the first stage in the process of the return of the Jews: "What a wonderful event ... the ancient city of the people of God is about to take its place among the nations, and England is the first gentile kingdom to 'stop trampling it' … What Napoleon planned through violence and pretension, we may exploit for the existence of our empire."

This mindset also had diplomatic implications. Muhammad Ali, who started off as a representative of the Ottoman government but eventually became an independent governor, conquered the territory of the Land of Israel and Syria a few decades later, in 1831, and ruled it to the displeasure of most European powers, except the French. This invasion provoked an international debate as to the future of the region, and to this end the Great Powers convened in 1840 in London.

Among other things, the idea arose to establish new Christian sovereignty or independent churches under Ottoman rule. Britain's stance against the establishment of independent Christian sovereignty stemmed from the efforts of Shaftesbury and his colleagues, who argued that the option of establishing a future Jewish state in the Land of Israel should remain.

The main editorial in the Times of London of 17 August 1840 stated: "A sustainable solution to the crisis in the East" should not be expected without "restoring the Jewish state". Despite the great diversity of languages and customs among the Jews, they still "continue to adhere with unbeatable tenacity to all distinct national characteristics," and therefore can "serve as an effective instrument for advancing the interests of civilization in the East."

Christian ideas about the return of the Jews to Zion, and even ideas about the establishment of a Jewish state, have been an integral part of the religious and cultural discourse in Europe since the French Revolution and were associated with seeing Jews as a nation with a glorious political past and present national vitality. These ideas also had an impact on the political sphere, and in particular with regard to Britain's policy on the "Eastern Question", the question of the future of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East.

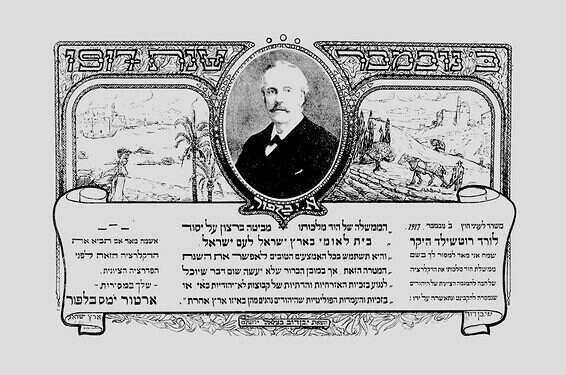

These currents of thought were integrated into the political interests of leading statesmen, and they incorporated them in rhetoric and sometimes even in their judgment, whether it was Napoleon, Queen Victoria, or Foreign Minister Palmerston. These currents were part of the background that led to the Balfour Declaration. Despite his skeptical nature, Lord Balfour was saturated with biblical education and sympathy for the cause of the Jews and their return to Zion, as evidenced by the following remarks: "The position of the Jews is unique. For them race, religion and country are inter- related, as they are inter-related in the case of no other race, no other religion, and no other country on earth." Only in light of this can Balfour's determination at the end of his life be understood: what he did for the Jews in the Balfour Declaration was the most worthwhile and worthy act in all his life's endeavors.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

Familiarity with the Bible and the story of the Jewish people in the Christian world and hopes in various Christian currents for the establishment of a Jewish state as part of the Christian redemption, were, therefore, an integral part of the cultural background within which the Balfour Declaration, San Remo resolutions and the League of Nations mandate recognized the historic connection of the people to the Land of Israel and its political significance.

Assaf Malach is founding director of the Jewish Statesmanship Center and head of the Committee for Citizenship Studies in the Education Ministry.