Former Minneapolis Officer Derek Chauvin was convicted Tuesday of murder and manslaughter for pinning George Floyd to the pavement with his knee on the black man's neck in a case that triggered worldwide protests, violence, and a furious re-examination of racism and policing in the US.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

Floyd, 46, died May 25, after being arrested on suspicion of passing a counterfeit $20 bill for a pack of cigarettes at a corner market. He panicked, pleaded that he was claustrophobic, and struggled with police when they tried to put him in a squad car. They put him on the ground instead.

Chauvin, 45, was led away immediately after the verdict was read with his hands cuffed behind his back. His face was obscured by a COVID mask, and little reaction could be seen beyond his eyes darting around the courtroom. His bail was immediately revoked. Sentencing will be in two months; the most serious charge carries up to 40 years in prison.

Defense attorney Eric Nelson followed Chauvin out of the courtroom without comment.

The verdict – guilty as charged on all counts, in a relatively swift, across-the-board victory for Floyd's supporters – set off jubilation mixed with sorrow across the city and around the US. Hundreds of people poured into the streets of Minneapolis, some running through traffic with banners. Drivers blared their horns in celebration.

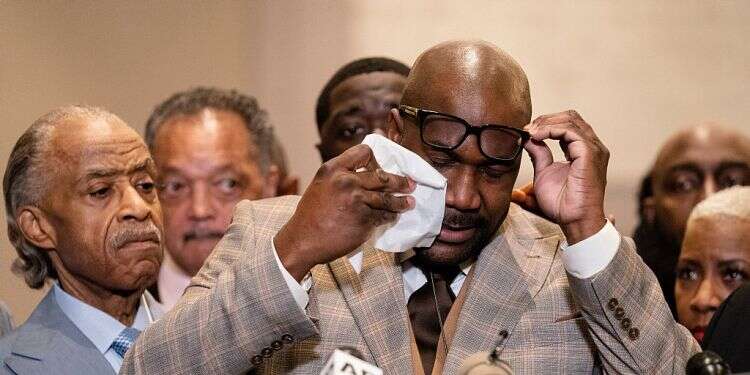

"Today, we are able to breathe again," Floyd's younger brother Philonise said at a family news conference where tears streamed down his face as he likened Floyd to the 1955 Mississippi lynching victim Emmett Till, except that this time there were cameras around to show the world what happened.

The jury of six whites and six black or multiracial people came back with its verdict after about 10 hours of deliberations over two days. The now-fired white officer was found guilty of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter.

President Joe Biden welcomed the verdict, saying Floyd's death was "a murder in full light of day, and it ripped the blinders off for the whole world" to see systemic racism.

But he warned: "It's not enough. We can't stop here. We're going to deliver real change and reform. We can and we must do more to reduce the likelihood that tragedies like this will ever happen again."

The jury's decision was hailed around the country as justice by other political and civic leaders and celebrities, including former President Barack Obama, Oprah Winfrey and California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a white man, who said on Twitter that Floyd "would still be alive if he looked like me. That must change."

At a park next to the Minneapolis courthouse, a hush fell over a crowd of about 300 as they listened to the verdict on their cellphones. Then a great roar went up, with many people hugging, some shedding tears.

The verdict was read in a courthouse ringed with concrete barriers and razor wire and patrolled by National Guard troops, in a city on edge against another round of unrest – not just because of the Chauvin case but because of the deadly police shooting of a young Black man, Daunte Wright, in a Minneapolis suburb April 11.

The jurors' identities were kept secret and will not be released until the judge decides it is safe to do so.

It is unusual for police officers to be prosecuted for killing someone on the job. And convictions are extraordinarily rare.

A sense of relief, of accountability, served and crisis at least temporarily averted, was palpable across the United States on Tuesday after a jury found Chauvin guilty of murder and manslaughter in killing Floyd, a Black man who took his last breath pinned to the street with the officer's knee on his neck.

But when it came to what's next for America, the reaction was more hesitant. Some were hopeful, pointing to the protests and sustained outcry over Floyd's death as signs of change to come, in policing and otherwise.

Others were more circumspect, wondering if one hopeful result really meant the start of something better in a country with a history of racial injustice, especially in the treatment of Black people at the hands of law enforcement.

With all the relief and gratitude 68-year-old Kemp Harris, a retired kindergarten teacher in Cambridge, Mass., felt upon hearing the verdict, it was tempered by what he'd seen in the much more recent past: The deaths of Daunte Wright in Minnesota and of Adam Toledo in Chicago.

Lucia Edmonds, 91, said she also let out the breath she hadn't even realized she'd been holding.

"I was prepared for the fact that it might not be a guilty verdict because it's happened so many times before," the Washington, DC, resident said. She recalled the shock of the Rodney King case nearly three decades ago when four Los Angeles officers were acquitted of beating King, a Black motorist.

"I don't know how they watched the video of Rodney King being beaten and not hold those officers to account," Edmonds said. About the Chauvin verdict, she said, "I hope this means there is a shift in this county, but it's too early for me to make that assumption." Still, she added: "Something feels different."

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

Beverly Mills, 71, of Pennington, New Jersey, and Elaine Buck, 67, of Hopewell Borough, New Jersey, found themselves thinking back through history as they reflected on the verdict in Minnesota.

"I was bracing myself for what would happen if he did get off," Mills said. "I couldn't even wrap my mind around it because I thought, then there is no hope." Mills said she was on her senior class trip to Washington, D.C., one of just four Black girls out of a class of 200 or so, when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968.

"Washington and all the major cities were starting to erupt and they wanted to get the kids back to New Jersey. As the train was leaving, you could see the smoke starting to circle in the sky," Mills said.

Will the verdict change anything? Buck said: "It will make everybody aware that we're watching you. We're videotaping. What else are we supposed to do?"

Things are and will be different, insisted Aseem Tiwari, an Indian American screenwriter who lives in Los Angeles. He's convinced the level of outrage spurred by Floyd's death would last, even if it doesn't take the form of sustained, nationwide protests as it did in 2020.

That kind of determination, he said, isn't just going to fade.