The blindingly bright sky, the birds of prey hovering in the silence, and the creeks that run through the dry, yellow ground give no hint of the drama that has played out in the mysterious caves of the Judean Desert in the last few years. Dozens of remnants of Dead Sea Scrolls and papyruses from the time of the Bar Kochba Revolt extracted from these caves and made public for the first time last month comprise the last chapter in the story of the battle between archaeologists and antiquities robbers.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

Sixty years after the first researcher of the modern era to probe the Judean Desert caves, Professor Yohanan Aharoni, discovered the famous "Greek Minor Prophets Scroll" in a cave near Hever Creek, a mission to track down antiquities thieves led authorities to the very same cave. It had become known as the Cave of Horror after the skeletons of 40 refugees from the Bar Kochba Revolt were discovered there, as well as three pottery fragments that bore the names of three of them. On the cliff that hangs over the cave there are the remains of a Roman camp that was apparently used by the forces pursuing the refugees, who died of hunger and thirst while sheltering inside the cave.

This past year, Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologists revisited the cave and were surprised to find fragments of 2,000-year-old scrolls that completed the ones Aharoni had discovered in the mid-20th century. Thus far, 10 lines have been decrypted, some from Zechariah 8: "These are the things that you shall do: Speak the truth to one another; render in your gates judgments that are true and make for peace. Do not devise evil in your hearts against one another, and love no false oath, for all these things I hate, declares the LORD."

The find was announced only in March, and now, for the first time, Amir Ganor, head of the IAA's Antiquities Robberies Prevention Unit, offers a broader look at the ongoing pursuit of antiquities robbers in the Judean Desert. This pursuit has led to many important archaeological finds, including the ones unveiled a few weeks ago. It also prompted a change in policy, with authorities now trying to beat the robbers to the treasure, rather than catching them.

Ganor has served as head of the unit for 20 years, and he admits that for many years, the robbers were "in control."

"They had an absolutely advantage on the ground. They knew every path, every furrow, every angle. For years, they went through the desert and the caves south of the Hebron Hills … and to a large extent, we were tracking them in the dark. It drove us crazy. For years, items were moving through the legal and illegal antiquities markets that could have come from only one place – the Judean Desert, whose dry climate preserves so well items from wood, scraps of scrolls, and papyruses," he says.

In 2005, this ritual was cut off for the first time when the name of Professor Hanan Eshel was linked to alleged violations of Israel's Antiquities Law.

Ganor goes back 15 years to touch on the scandal that rocked the archaeological community. "In 2004, robbers at a cave in Arugot Creek found a scroll with three fragments of verses 23-24 of Leviticus, which had been written down at the time of the Bar Kochba Revolt," he says. Eshel bought the scroll from the robbers at a bargain price, $3,000, with funding from Bar-Ilan University. He did not report the transaction to the Israel Antiquities Authority and was nearly tried for it.

But what is less known is the unit's work tracking down that scroll.

"One day," Ganor recalls, "We got a report from an informer about a scroll from the Judean Desert. It later turned out to be the Leviticus Scroll, and it was in the market. We later received a photo of it. To get a hold of it, secure it and get to the people who had it, the robbers and the buyers, we decided to put on a show and operate our own gang of 'robbers,' a group of Arabs and Jews disguised as antiquities thieves."

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

"We outfitted them with an old Jeep, metal detectors, and digging tools. We made them part of the landscape. Once a week, members of our gang would ask the members of the [Bedouin] Rashaida tribe to watch the jeep. So for three months, our 'robbers' would hand the jeep over to the Bedouin and go out to look for antiquities. The Rashaida didn't buy it until, in coordination with the IDF, we set up a patrol that passed right by us and offered to work with us. We won the trust [of the Bedouin], we made friends with them. They were the first ones to tell us about the Leviticus Scroll, where it was, whom it was given to, and to whom it was sold. At the end of the operation we arrested three antiquities robbers, members of the Dafalla family of the Rashaida tribe, and Professor Eshel, who had bought the scroll, handed it over to us."

Four years later, in 2009, the unit received information from two sources about another rare document, a papyrus that would later be identified as the "Year 4 to the destruction of Israel" papyrus, a legal document that belonged to a widow who was involved in a lawsuit over her property. The papyrus was apparently written in the year 140 CE, at the end of the Bar Kochba Revolt, after the rural Jewish community in Judea was destroyed. The document contains 15 lines that mention, among other things, the names of three ancient Jewish villages south of the Hebron Hills (Beit Amar, Upper Anav, and Hurvat Aristobulus), evidence that the Jewish community there continued to exist even after the revolt.

This time, Ganor and his people picked up the trail thanks to a gang of robbers from the village Sair, members of three families who at the time were "active" in the Cave of Skulls at Zeelim Creek. The robbers, it turned out, had put the papyrus up for sale via Christian brokers form Bethlehem.

This time, members of the unit disguised themselves as buyers bidding against other real customers – both antiquities dealers and academics. The fake buyers represented themselves as acting on behalf of an American collector who was supposedly eager to purchase the papyrus. Meetings were set up repeatedly, but each time, something else went wrong.

The defining moment came in a room at the Hyatt Hotel in Jerusalem. A fake representative of the fake collector arrived carrying a suitcase filled with $2 million of fake money. The brokers brought the rare artifact with them and were arrested on the spot. Eventually, in 2016, a rescue excavation in the Cave of Skulls – to which Jews also fled during the Bar Kochba Revolt – turned up pieces of papyrus inscribed with the same writing as that of the Year 4 apyrus, which researchers think might have come from the same cave.

The more operations the unit launched, the more sophisticated the robbers became.

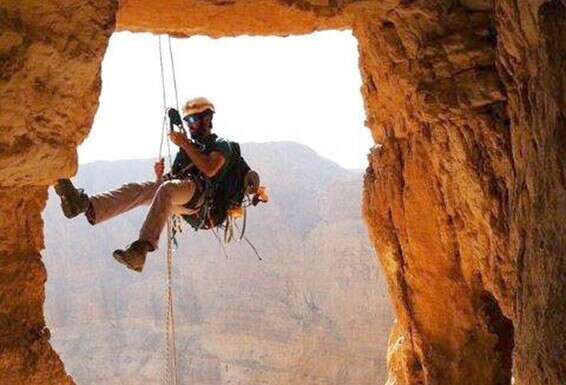

"The members of the gangs used advanced climbing and rappelling equipment and sophisticated metal detecting equipment. They improved their skills climbing cliffs as part of their work in the quarries around Beit Fajjar," Ganor says.

According to Ganor, the robbers also used academic material about the extensive archaeological activity in the Judean Desert in the 1960s, as well as maps and plans that were published as part of that research.

Slowly, members of the unit grew more familiar with the territory and decoded the relations between three Bedouin tribes and the gangs of robbers who came from the villages Sair and Bani Na'im, and how they divided the territory among themselves.

In April 2013, a source presented Ganor with the Jerusalem Papyrus in exchange for tens of thousands of dollars. The papyrus, which dates from the 7th century BCE, features six words in ancient Hebrew script. This was one of the earliest and most exciting documents ever found, the first archaeological discovery that dated to biblical times – other than books of the Bible – to be discovered in Israel and mention Jerusalem by name. It was a bill of lading for a shipment of wine sent to Jerusalem from the city Naarata. Once again, the trail led to the gang from Sair. At this point, the unit decided to loop Israel Police search and rescue units from Ein Gedi, Arad, and Megillot, as well as the Cave Research Center at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, into the operation to prevent antiquities theft.

In May of that same year, "Operation Eagle" began. The immediate goal were to try and identify the cave from which the Jerusalem Papyrus had been stolen as well as map the caves of the Judean Desert where artifacts dating back to the biblical era had been found and increase the number of people working with the unit.

"In mid-2013, we went back to our old system of forming ties with the gangs of robbers, sending in more and more people and also disguising ourselves as traders. It also requires a good cover story. It's a little like infiltrating a crime family. You can enlist someone from inside the family itself, or make the family want to work with your agent.

"This time, it took, nearly two years, but we managed to penetrate another gang from the clan in Sair. We ran around in the desert with the robbers, we became part of them. It wasn't easy. You have to provide your agent with security. A tiny mistake that could make him suspicious, and he's burned. There were at least three teams watching his activity from near and far, able to get to him in minutes," Ganor says.

"Sometimes, we managed to oversee what the robbers were taking out of the caves by buying the items. In other cases, we went into the caves after the robbers, to understand the territory and research it."

The turning point came in the summer of 2013: "One night in June, we got a report from the Arad search and rescue unit about Palestinians who were stuck on a cliff at Arugot Creek. We got there right away. We identified ourselves as police, not as the IAA. The search and rescue unit brought them down off the cliff and we questioned them. We got their details, their IDF cars, and when we searched their car we found maps, digging equipment, flashlights, and pickaxes. Bingo. But we decided to let them go. From that moment, they became our guides, and didn't suspect a thing. The way they saw it, Jews were suckers who had rescued them without realizing who they were."

"It went on for a few months, until one Saturday in November 2014, when completely by chance, things came full circle."

It happened while the Arad search and rescue unit were training. One member of the rescue unit, Uzi Rothstein, was trying out a new camera with a zoom, and aimed it at the nearby caves. To his surprise, he spotted two figures at the opening of the Cave of Skulls, on the north bank of Zeelim Creek. One was holding a metal detector. Rothstein sent the pictures to Ganor, and all members of the unit were scrambled to the top of the cliff, 80 meters (262 feet) above the opening of the cave.

"We dug in," Ganor says. "We told ourselves that even if it took three days, it was their only way out. At one stage, when they realized they'd been caught, one of the robbers tried to rappel down and fell off the line. His friends pulled him back up. Eventually, they had no choice. They climbed up as the light was fading. We caught six, with all their equipment. Two of the six were the ones who had been rescued off the cliff at Arugot. For us, it was a huge success. The robbers took care to leave most of what they had found in the cave there, but they weren't careful enough, and in their tools we found a 9,000-year-old arrowhead and an ancient lice comb. It was enough to put them in prison for 18 months."

"After we caught them, we went into the Cave of Skulls and realized that the Jerusalem Papyrus hadn't come from there, but it was still a turning point," he says.

A new director of the IAA had just been appointed – Yisrael Hasson, a retired Shin Bet security agency agent. He challenged Ganor and the rest of the unit. The Cave of Skulls was excavated with the help of hundreds of volunteers, and it was fruitful. Finds from the cave included a trove of jewelry and beads from the Chalcolithic Period (some 6,000 years ago), more finds from the Bar Kochba revolt, and more.

One day, Hasson arrived at the cave. Ganor says that the IAA head, moved at the sight of young volunteers devoted to their work, asked him, "Amir, why do we get to these caves after the robbers? Why don't we beat them to it? Why don't we stop running after the mosquitoes and start drying up the swamp?"

That was the moment the record changed. A few months later, the IAA's Orange Unit was established – a unit mandated to go through the caves of the Judean Desert, under Ganor's authority. It's 11 members included three archaeologists.

"We took the initiative and ran with it. People underwent advanced training in rappelling, climbing, rescue. The project to survey the Judean Desert caves was on its way. It's been running for three years, with an annual budget of 9 million shekels [$2.7 million]. We shoulder a third of that, a third id paid by the archeology division of the IDF Civil Administration, and a third by the National Heritage Plan in the Prime Minister's Office."

Ganor explains how it works: "We choose a creek and swarm all over it. We send up drones. We film the creek and mark cave openings. We plan how to access each cave. We design a work protocol and send information to a computerized system that will provide an orderly database for future generations. Anyone who comes after us can click on a point on a map and get all the history and potential of the place."

In the past three years, the unit has mapped 120 kilometers [74 miles] of cliff – 400 caves. Of these, 12 have been excavated. In one, which had been visited by robbers, archaeologists discovered the scraps of the 2,000-year-old scrolls. Another cave south of Qumran, in which no human had set foot since refugees fled there in the Bar Kochba Revolt, revealed vessels and coins. In yet another cave, researchers found jugs that had once held scrolls, but the scrolls themselves were gone.

However, Ganor says this is likely not the handiwork of thieves. "There were no tracks. It's a mystery we'll have to suggest an answer to. It's possible that Byzantine monks who wandered around the Judean Desert collected the scrolls in the fifth century CE. Who knows? Maybe the scrolls are still in archives at those monks' monasteries – possibly the Mar Saba Monastery?"

Ganor says that in 95% of the Qumran caves the unit entered, there were signs of antiquities theft, "which only show how helpless the government was for many years. This last operation has changed things for the first time. We are now in charge of the Judean Desert. From the moment our people were present in the desert every day, with tents and equipment, the message got through.

"To a large extent, we've restored governability when it comes to antiquities in the Judean Desert, through cooperation with the Israel Nature and Parks Authority and the Civil Administration's archaeology unit. I just hope that in the fourth year, the budget will allow us to continue, because at the moment we're working with a very limited budget. We wouldn't want things to change again," Ganor warns.