We've almost forgotten the true reason for urban renewal projects in Israel. A Tel Aviv University study conducted this past year at the bottom of the Dead Sea warns that an earthquake measuring 6.5 on the Richter scale can be expected to strike within the next few years. The average cycle of earthquakes in the region is one per 130 years, but there are exceptions, with less time passing between quakes.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

How long does it take to obtain a permit for urban renewal projects in different cities (according to data and research provided by the Madlan website)? In Bnei Brak: 1 year (39 projects), Kiryat Motzkin: 1 year (22 projects), Zikhron Ya'akov: 1.1 years (10 projects), Hadera: 1.2 years (12 projects), Kiryat Bialik: 1.2 years (42 projects), Herzliya: 2.4 years (32 projects), Tel Aviv: 2.6 years (181 projects), Bat Yam: 2.6 years (20 projects), Givatayim: 2.8 years (11 projects), Ramat Gan: 3.25 years (42 projects).

Everything operates in slow motion and goes on for years. Take, for example, the renewal of Netanya's rundown Romanian Neighborhood, as it is called, in the center of the city, near HaAri Bridge. The neighborhood's buildings are dilapidated. Its renewal project was launched twenty years ago, but construction has just begun.

Netanya's Mayor Miriam Fierberg-Ikar: "This is one of the most important projects approved this year by the District Committee. It combines lands plots and buildings intended for demolition and reconstruction with private agricultural lands to be used as supplementary land, on which some of the new housing units will be built."

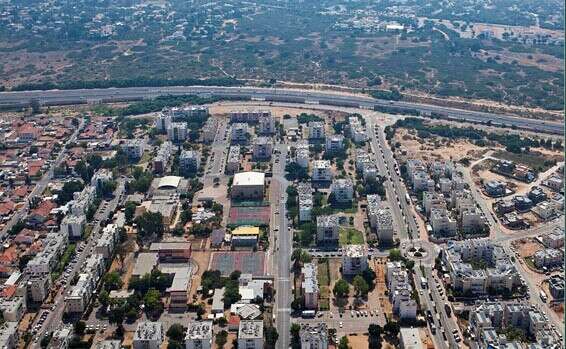

The urban renewal project in Giv'at Shmuel also took twenty years to come to fruition. The dream of owning an apartment seemed more distant than ever for the residents of 21 public housing buildings in Giyora Neighborhood – buildings that were deemed unfit for habitation. All the neighbors had already signed the paperwork and were prepared, psychologically and financially, for the prospect of urban renewal; however, legal complications and lots of red tape made it seem impossible to realize. Or, as one resident put it: "We raised the property's value based on its potential, but continued living in a dump."

About four months ago, the National Committee for Planning and Building Preferred Residential Complexes finally approved the Giv'at Shmuel plan, which will include 1,831 new housing units to replace 552 crumbling public housing apartments. The existing buildings will be converted into 18 new, 9- to 30-story buildings, including two office towers.

Yossi Brodny, mayor of Giv'at Shmuel: "This is a major development for the city and its residents. The plan was prepared based on a comprehensive urban approach that took into account transportation needs, environmental development, infrastructure, bicycle lanes, parking spaces, and green areas, and is expected to improve the city's appearance and quality of life. I sincerely hope the Israel Land Authority will understand the importance of this project and advance its implementation as quickly as possible."

Niv Rom is the CEO of Cnaan Group, a company that specializes in urban renewal projects and did much to promote the demolition-reconstruction plan in Giv'at Shmuel, where it is a stakeholder in the new residential complex. Rom says that "it was only after a long period of professional work that the plan was finally significantly improved."

A High-Risk Enterprise

An urban renewal project takes, on average, 12 years to complete, even without a pandemic. The past year's crisis caused additional delays. The fact that Israel has no functioning government generates uncertainty in the field of urban renewal as well. There is still no law to replace the TAMA 38 program, and the Urban Renewal Fund lacks any significant budget and exists in name only, its leaders soon to be replaced.

According to Dun & Bradstreet data, in 2020, about 350 urban renewal companies failed financially; another 250 are at high risk of failure.

Urban renewal is a mainstay of the Israeli real estate sector, with about 1,400 developers active in the field. About 30,000 urban renewal housing units are currently in different stages of construction. The annual financial scope of these projects is estimated at about NIS 20 billion, representing about 20% of the residential real estate sector's aggregate revenue.

The problem is that 75% of construction is executed in the country's strong central area. In the cities along the Syrian-African Rift, which are most at risk of earthquakes, the national building reinforcement program has barely been implemented, despite the fact that Tiberias, Beit She'an, Safed, Arad, Beersheba, and other historical cities along the fault line have been intermittently devastated by quakes throughout history.

Thus, a tsunami once hit Caesarea's Herodian Harbor – a fact that did nothing to shorten the approval process of an urban renewal project in the nearby town of Or Akiva, planned by Tidhar, Shikun & Binui, and NSA. The project awaited approval for over a decade, and construction has only recently finally begun.

This year saw a decline of about 15% in urban renewal housing starts compared to 2019. Yet, due to the general decline in housing starts in Israel in 2020, the urban renewal field retained its relative size, representing nearly 20% of total housing starts.

2020 also saw a drop in the number of permits issued for new projects, not least due to disruptions in the activity of planning authorities. Some projects took longer than forecast; in others, lockdowns caused delays, and some companies suffered a decline in sales.

Another problem is that city mayors are dominant in the project approval process, with each municipality taking its own approach. "There is no procedure that obligates all municipalities," says Yehuda Katav, Chairman of the Contractors' Association in the Tel Aviv and Central Districts and Vice President of the Israel Builders Association. "Every city speaks its own language, and so does each bureau or district committee, which slows down processes."

What can be done?

About 70 thousand urban renewal housing units are expected to join the real estate market in the next few years. The proportion of apartments in the Jerusalem District, the Southern District, and Judea and Samaria is forecast to rise at the expense of the Tel Aviv and Central Districts. Yet, "even after this shift, the Tel Aviv and Central Districts are still expected to make up 55% to 60% of the sector's activity," says Efrat Segev, VP of Data and Analytics at Dun & Bradstreet.

Tel Aviv has found an interesting way of shortening the cumbersome approval process: in certain areas, the municipality itself initiates the urban building plan, rather than placing its advancement in the hands of a private developer. After the plan is approved, the municipality publishes a tender and a developer executes the project. "This kind of mechanism makes it easier to move plans through the system," explains Architect Lilach Mor, VP of Netivey Hakama Ltd.

In cities near the northern border, barely any buildings have been reinforced; the same is true in the Gaza envelope area, where projects are tough to push through. The state, local committees, and the tax authorities can change this reality by means of incentives for developers. "National collaboration is needed to revitalize these cities," says Nir Shmul, CEO of the Company for Development and Urban Renewal.

Itai Smadar, VP of Urban Renewal at the Rotshtein Company: "One of the main challenges facing large cities in approving major plans is dealing with high housing density, overburdened infrastructure, and a shortage of public spaces. Creative solutions are needed. During the pandemic we allowed project planners to set aside land for the municipality and communal spaces for residents, without reducing the apartment or building size. This benefits all sides – the residents, the municipality, and the developer."

Amir Cohen, VP of Marketing at YH Dimri: "There is an inherent conflict of interest between the district committee and the developer regarding the number of housing units to be constructed. Local councils are concerned about the lack of financial resources and public infrastructure that can suppport an increase in housing density, while the developer seeks to add housing units to improve profitability. The solution is simple: appoint appraisers who are experts in project accompaniment and financial checks, who will arbitrate between the committee and the developer."

Ran Malach, CEO of Bonei HaTichon Urban Renewal: "Although local authorities understand the necessity of urban renewal plans, they definitely find such plans challenging. In Kiryat Ono, the head of the local authority set a clear policy, and the professional level – led by the Municipal Engineer, the chief of the Licensing Department, and the head of the Urban Renewal Administration – implemented the policy, understanding that these processes serve not only the apartment owners in the specific complex but also the complex's immediate surroundings and all of the city's residents. This created a platform for fruitful activity, which soon yielded positive results.

"The main problem in large cities, where the scope of urban renewal projects is greatest, is housing density and overburdened infrastructure, particularly public facilities. One solution is based on the concept of shared spaces, which has gained popularity mostly in an employment context, but not just there. Local authorities now encourage developers to create shared public spaces for residents, particularly on ground floors. These spaces sometimes come at the expense of various amenities for residents. Yet despite the challenges, we have been seeing greater understanding and general willingness on the part of local authorities to advance such plans."

"Urban renewal is usually a common interest of all the parties involved," sums up Tal Kopel, deputy CEO of Madlan. "But often there is mistrust between the sides, which causes delays. These can happen at almost any stage of the project – the agreement in principle, the planning stages, and finally the construction stage – and depend not only on the good will of the parties but also on the professionalism of the developer. It is very important to check who the developer is and what his record is, using tools that grade professionals in the field."

How is a renewal plan promoted?

In the first homeowners' meeting, find out the percentage of residents who agree to the plan. Even if you reach the majority required by law, experience shows that few developers will choose to cooperate when there are residents who oppose the plan. It is therefore crucial to speak in person with neighbors who raise objections.

Try to understand the reasons for their opposition. Set a meeting with the dissenters. Show respect and don't get too excited about all-encompassing objections, even if they are bluntly put. Approach each objector and emphasize the component of the plan important for him or her. Emphasize the advantages of adding a security room in each apartment and an elevator that will benefit the building's older residents.

In some cases, an apartment owner cannot continue residing in the building during the reinforcement or renovation process, due to health issues. In these cases, the law obliges the developer to cover the costs of renting a different apartment for that resident until construction is completed.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

In demolition-reconstruction projects, if the apartment owner is aged 80 or older when the permit is obtained, an amendment to the law requires the developer to offer the owner the value of his future, rebuilt apartment at the time of evacuation, so the resident does not have to move to a rented property.

If one resident remains who continues to oppose the plan for no logical reason, the other apartment owners can sue, and the objector may find himself accountable for the financial damage caused to the other residents due to his opposition. In court rulings on this issue, land inspectors have clearly tended to deny objections and allow urban renewal plans to go forward.

(Adv. Ravit Sinai, author of the Guide to Tama 38 and Demolition-Reconstruction Projects)

This article might include sponsored and commercial content/marketing information. Israel Hayom is not responsible for its nature or its credibility. The publication of such content or information shall not be considered a recommendation and/or an offer by Israel Hayom to purchase and/or use the services or products mentioned in this article.