Anna Whitty has only vague memories of her grandfather, Wojciech Rychlewicz. He died of cancer in 1964, when she was eight. "As a little girl, I remember he was very tall and scary," she says in a phone call from her home in England. "He came from a very good family. My grandmother, his wife, did not have enough pedigree for his family. She studied in England before World War II, so she spoke good English that allowed them to get along in Britain after the war. It was quite rare for a Polish girl at that time to study in England and it surprised me when I found it out."

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

There, however, was one thing in what she does remember about her grandfather that bothered her: "My grandfather's death certificate stated that he was a clerk, meaning he had a modest position in the Polish administration. However, he ended the war as an officer in the Polish army. Many families of Polish officers, who came to London after the war, bought here large and spacious houses from the money they had brought. Their families lived in very comfortable conditions. Their sons and daughters became architects, doctors and engineers. But my grandparents had a different lifestyle.

"First, they sent my mother to boarding school - something I cannot forgive them. I have in my possession several diaries of my mother from that period, which testify to how much she hated life there. Second, they spent all the money they received when we came here on renting a large building, where single young people (Polish refugees) were given shelter and a family atmosphere. They, themselves, ended their lives in a small apartment in public welfare housing. This was, admittedly, very common among the British population after the war. But, there was a huge gap between the standard of living of the other Polish families in London and my grandparents, who helped other people, and needed help from the British state at the end of their lives. I never understood that. Why did they have to cope with financial difficulties, while other Polish families lived comfortably in West London?."

Until recently, Whitty, who also uses a shortened version of her name "Hania", knew very little about Rychlewicz. Her family, a Polish immigrant family in Britain, did not talk about what he had done during the Second World War. But, the fascinating story of his life has been slowly revealed to her in recent months. Wojciech Rychlewicz (1903-1964) was the head of the Polish Consulate General in Istanbul in the early years of WWII and was responsible for the rescue operation of Polish Jews who fled from the Nazis and the Soviets, an operation first revealed here.

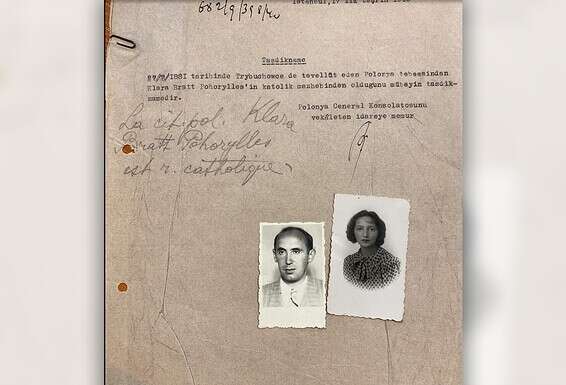

Using his position, Rychlewicz issued hundreds of false official documents confirming that Jewish refugees, who arrived in Turkey and sought to immigrate to other countries, were Christians. This apparently enabled hundreds, possibly thousands, of Polish Jewish refugees to emigrate to Brazil, other countries in Latin America, and then-British Palestine.

In issuing these false official certificates, Rychlewicz took a very big risk. As far as is known so far about this rescue operation, Rychlewicz did not demand money for his services. His and his wife's post-war lifestyle is evidence that the ex-consul – unlike some diplomats, did not get rich from rescuing Jews. This affair is another piece in uncovering the important role played by Polish diplomats, who represented Poland's exiled government in London, in efforts to save Jews during World War II.

It is doubtful that the rescue operation of the Polish consul in Istanbul would have been revealed had it not been for the determination of dr Bob Meth, a Jewish doctor from Los Angeles and a former member of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, [delete "in the United States"] to reveal the identity of the man who saved his mother, grandfather and other relatives in those tumultuous times of World War II.

"My mother, Ellen C. Meth, whose birth name was Edward Wang, wrote a summary of her life in honor of my nephew's bar mitzvah about 20 years ago, in which she told about the rescue of her family in Istanbul," Bob tells "Israel Hayom": "It's her memories so that her grandchildren can understand the Holocaust in person, through her life experience, so that they can identify with the subject. She just did not know the identity of the man who issued the family the certificates of their being Christians, in order to obtain immigration visas. My mother was born in Krakow in 1922 to a family living in Rzeszow in southern Poland. Her father was a wealthy landowner. In 1939, he decided to travel to the New York International Fair, which opened on April 30, four months before the German invasion of Poland, which marked the outbreak of World War II. He wanted to go with my grandmother and mother, who was their only child. But my grandmother, Mira, decided to stay behind. America did not interest her. So my grandfather took my mother to New York in the spring of that year.

"He had relatives there and they spent several months in the United States. At that time, my father bought an apartment building in Brooklyn and thus officially became a property owner in the United States. My mother and father returned to Poland at the end of August, a few days before the outbreak of the war, in the hope that the Polish cavalry would be able to repel the Germans and defend their country.

"A few weeks after the outbreak of the war, they moved to Lvov, today a city in Ukraine, which was then in the Polish territory occupied by the USSR. My grandfather also had property there. Since he and my mother still had visas to the United States from their last trip, even though these were only one entry visas, they managed to leave Poland. The family wanted to move my mother to a safe shore as soon as possible. So they left my grandmother with gentile friends in Lvov, wanting to join them in my house later.

"My grandfather and mother left Lvov for Odessa, and from there traveled to Istanbul where they stayed for three months. They desperately moved from one consulate to another in an attempt to obtain visas, which would allow them to bring my grandmother from Lvov as well. Meanwhile, they met the son of a non-Jewish Polish acquaintance, who referred them to the Polish consul in the city, to make it easier for them to obtain immigration visas to Brazil. A document issued to my grandfather states that he, Szymon (Simon) Wang, a "Catholic born into a Catholic family" of Józefand Maria Wang (Joseph and Mary were the names of Jesus' parents), as well as his entire family and his brother's family who also came to Istanbul. "The Soviet occupation made it difficult for my grandmother to leave Lvov and she was eventually murdered in Auschwitz," Meth says.

In her memoirs, Ellen Meth described what happened to her and her father in Istanbul: "We sipped 'raki' on the terraces of little cafes in Taksim, the innocuous licorice-taste running to my head like a series of tiny, lovely explosions. We sat on the steps of the Blue Mosque, watching the vast white shape of Hagia Sophia against the ink-blue sky. It was Summer, and every Sunday we took a boat ride to one of the many islands or beaches on the Bosphorus and spent the day there.

"Leaving Turkey and getting my mother out of Poland were my father's main concerns. Like hundreds, thousands of others, we were safe in Istanbul but had no place to go. Although I was happy on a personal level I, too, felt the stress and anxiety that permeated the very air that surrounded us. We spent our days going from consulate to consulate, waiting in endless lines just to get a visa application or to speak to some official without ever getting any encouragement; no country seemed to be inclined to offer us refugees. We applied for entry visas to countries we never even heard of and exchanged information about immigration possibilities with all the other refugees whom we met at the HIAS. Since my father only spoke Polish, German and Yiddish and I spoke French rather well in addition to having some knowledge of English, I acted as interpreter. I was very much involved in everything that was going on.

"It was by sheer accident that we ran into Mr. Daniec, a young attorney, son of our landlord in Rzeszów, who told us that the Government of Brazil had 10,000 immigration visas for Catholic citizens of Poland, Mr. Daniec and his wife, both of them Catholics, were planning to go to Brazil on those visas. Polish Jews, however, had to have $10,000.00 in Brazil in order to obtain the visa. Young Mr. Daniec suggested that we obtain baptismal certificates "just in case" (I still have my father's 'baptismal certificate' stating that my grandmother's name was Maria and my grandfather's Joseph), and that he would then take us to the Polish Consulate for further certification of our status.

"Like Sugihara in 1940, [Japan's consul in Lithuania who risked his career and his life by churning out Japanese transit visas for almost 10,000 Jews who wanted to escape the advancing Nazis], the Polish consul in Istanbul issued countless affidavits to Polish Jews trapped in Turkey. He certified under oath that they were Roman Catholics, knowing that they were not, and the only criterion was that they have Polish or neutral-sounding surnames. After we had obtained our affidavits, we in turn, like Mr. Daniec in our case, brought acquaintances to the Polish Consul and certified that they were Christian and thus enabled them to get entry visas to Brazil. These people, too, brought their friends and acquaintances to the Polish Consulate for 'certification'. What made the Polish Consul act the way he did? Was it simply an act of goodness, an act of decency? I know for a fact that no money was exchanged. My only regret is that I do not remember his name for he surely deserves to be remembered and honored for having saved hundreds of Jewish lives.

"With a certificate in hand, confirming our status as Roman Catholic citizens of Poland, getting the Brazilian visas was easy. We were the first 'Jewish Catholics' to apply, and part of the routine was a medical examination by the official Brazilian doctor, who simply could not understand why my father and Uncle Fulek were circumcised (…) As always, I acted as interpreter, and we had a few anxious moments when I simply 'did not understand' what the doctor was asking about when he questioned my father's and uncle's circumcision. We obtained the Brazilian visas at the end of July and then spent days in the various consulates getting the necessary transit visas."

All this is relayed in the testimony of Ellen Meth, who passed away in 2013 in New Jersey at the age of 91.

The fictitious Christian documents and immigration visas to Brazil did not allow Ellen's mother to leave the Soviet-occupied zone, as she had been forcibly made a USSR citizen and as such, she was barred from leaving the country. Ellen's father tried another attempt: he managed to obtain Nicaraguan citizenship for himself and his wife, apparently for a hefty fee paid to the Nicaraguan consul in Istanbul. These illegitimate documents could have allowed them to leave the USSR, but not to enter Nicaragua. The documents were transferred to Moscow, but to no avail.

The visa to stay in Istanbul, which was good for only three months, was about to expire, and Ellen, her father and his brother's family continued their wanderings, on their way to America, when land and sea travel from country to the country became extremely difficult due to war.

"My grandfather and mother had to leave Istanbul," Bob, who was born in 1954 in New York, continues, "They went on to Damascus, Baghdad, and from there to Bombay. They lived there for several months. Because of my father's property in New York, they tried to get a visa to enter the United States. Due to the war, Poles could not leave their country, so there was a surplus in the quota of visas for Poles, and so they managed to obtain a visa to the United States.

"My grandfather's brother, who had no property in the United States, went on to Shanghai. My grandfather and my mother went to Japan and boarded a ship that brought them to Seattle and from there by train to New York, where they settled' [This was still before Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of the US-Japanese War]. My mother was always curious to know who was the man behind the credentials that allowed them to move on," Bob emphasizes, "but, to the best of my knowledge, she did nothing to find out."

"Because of my parents' experience as refugees in World War II – my father escaped from Vienna in 1939 and came to Britain - I have been very active in Jewish organizations since my youth. By the way, my parents did not allow themselves to be called Holocaust survivors because they did not experience the Nazi camps. But, as teenagers, they were forced to leave their country and their homes.

"I grew up in New Jersey and in the early 1970s we were very active in the fight to obtain freedom for the Soviet Jews. One of the activists in the Jewish youth movement there with me was Michael Oren, who later became Israel's ambassador to the United States. I was later appointed chairman of the movement for the Soviet Jews, now called the National Coalition for the Support of Eurasian Jewry. This appointment made me a member of the Conference of Presidents of Jewish Organizations in the United States.

"I returned to activity at the 2015 Presidents Conference. Every year the members of the conference travel to Jerusalem and before that stop at a place of interest to the Jewish world. In 2015, we stopped in Vienna, because of its international institutions and because negotiations on the nuclear deal with Iran were taking place there at the time. We organized a dinner for us, and one of the guests was the Polish Consul General who was about to leave for a period of service in Istanbul. I told him my mother's story, and asked him to find out who the man who issued documents was to save my family. He did nothing, but through my contacts with the Holocaust Museum in Los Angeles I reached out to JarosławŁasiński, the Polish Consul General serving in that city and he connected me to the new Polish Ambassador to Turkey, JakubKumoch, who recognized who was the man who signed the documents."

Ambassador Jakub Kumoch had already contributed, while serving as his country's ambassador to Switzerland, to the revelation of another Holocaust rescue case during the Holocaust, carried out by Polish Embassy and consulate employees in Bern. Following this revelation, which we reported extensively on "Israel Today," Yad Vashem awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations to the consul in Switzerland during the war, Konstanty Rokicki.

Yad Vashem is still considering the application to bestow the title to Ambassador Aleksander Ładoś for the part he played in the production of thousands of South American passports, which contributed to rescuing several thousand Jews.

Kumoch asked one of his diplomats to check the information Bob had provided in the Archiwum Akt Nowych (AAN) in Warsaw. In July, they located in the archive hundreds of nearly identical documents, each of which was dated 1940-1942, most of them in French - the diplomatic language of those days - and some in Turkish and Polish. All of these documents evidence the scope and complexity of the secret rescue operation. A large part of the documents confirmed the belonging of people with clearly Jewish given names and surnames to the Catholic Church.

Quite a few documents confirm the emigration of the recipients of the documents to travel to then-British Palestine. It follows that the Polish consulate in Istanbul issued fictitious "Christian certificates" to Polish Jews not only so that they could overcome the difficulties of immigration to Latin American countries, but also so that they could circumvent the immigration restrictions imposed by the British Mandate authorities.

The White Paper, published on May 17, 1939, following the Great Arab Revolt in Israel and in the time when Jews in the Nazi Reich - Germany, Austria, and annexed parts of Czechoslovakia, desperately sought refuge from Nazi persecution, set a quota of 75,000 Jews for the next five years. 25,000 were allowed to immigrate immediately and every year thereafter the immigration of 10,000 Jews was approved.

These quotas were set only four months before the German and Soviet invasions of Poland, the country where over three million Jews lived. At the beginning of the war, tens of thousands of Polish Jews fled east from the Nazis, and found themselves under Soviet occupation. Whoever could and had good reasons to flee from the Soviets continued on, south - to Romania, to Bulgaria, and from there they tried to reach neutral Turkey. Before the war, there were 450 Poles in Turkey, 400 of them Jews.

Neutral Turkey served as a passage for Jewish refugees to other countries including Eretz Israel. However, the Turkish government - which since the late 30. has implemented an official policy of discrimination against Jews and other non-Muslim minorities – has allowed only 200 Jewish refugees to remain in Turkish territory at a time.

Germany, for its part, exerted heavy pressure on neighboring countries not to allow Jews to move to Turkey. Hence the assumption that the certificates of Christianity were also issued by Rychlewicz in order to circumvent this restriction and allow more Jewish refugees from Poland to find temporary refuge there. The fictitious documents also served as certificates of integrity: they usually also included mentions that their bearers were honest and well-known to the consulate, important professionals and wealthy.

"The 1930s was the period of the country's Turkification," explains Metin Delevi, a member of the Jewish community in Istanbul who wrote several books on the modern history of this old community. "It should be noted that all non-Muslim minorities have been harmed by this policy, not just the Jews. Anti-Semitic writers continued their publications throughout the decade. We must also not forget the conscription into the army of non-Muslims in 1941 and the property tax of 1942, which was imposed on all religious minorities but the Jews were the ones most affected by it. And from 1943, when the defeat of the Germans was on the horizon, everything changed: the anti-Semitic publications disappeared almost completely, and a Jew, Avram Galanti, was elected member of parliament.

"In general," Delevi emphasizes, "transit visas through Turkey were only issued to people who had a visa to enter another destination, such as Palestine-Israel. This directive was in effect until 1943, except in a few exceptional cases. Only after the sinking in the Sea of Marmara in December 1940 of the ship Salvador (which had about 240 Jewish refugees who tried to reach Bulgaria from Palestine and about 200 of them drowned), residence visas were granted to 4,000 Jewish immigrants for a short period. However, from 1944 Turkey opened its borders to refugees - mainly from Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and even Hungary. I knew a Hungarian who, when he was 9, moved to Istanbul with a group of Hungarian Jewish children and stayed there for ten days. '

Q: Have you heard of the rescue operation of Jewish refugees, carried out by the Consul General of Poland in Istanbul since 1940, in which Christian certificates were issued and distributed to Jews who wanted to continue to Palestine-Israel or Latin America?

"I actually did not know this story until about four months ago, when the new Polish ambassador to Turkey who worked on this issue brought it before us. Following this conversation, I did a little research. Yad Vashem also confirmed the possibility that the story was true. They have not yet awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations to the Consul who was involved in the operation. I hope to get more details on the affair soon."

Yad Vashem said in a statement, "Recently an information request regarding this subject was received by "Yad Vashem", which is now under examination. This is an examination of historical facts and research of archival materials that could assist in verifying the issue."

Q: Was there an organized passage of Jewish refugees through Turkey to Israel, first across Syria and after its conquest by Vichy France at sea through the port of Mersin?

"Chaim Barlas and Teddy Kollek – two representatives of the Jewish Agency in Istanbul, organized the immigration of Jews, mainly through Syria and more rarely from the port of Mersin to Haifa. According to some sources, some 27,000 Jewish immigrants who passed through Turkey came to Palestine-Israel, and this does not include the crossings that were made individually. However, most of the organized transports took place after 1943."

The Jewish refugees, who obtained certificates (immigration visas to Israel) from the British as Jews or Christians, had several routes to get from Turkey to Israel in the first months of the war: traveling by train from Istanbul to Tripoli in Lebanon or Aleppo in Syria and from there by car to Haifa. Another option was traveling by train to the Turkish port city of Mersin, from where two ships regularly sailed to Haifa.

In order to enter Turkish territory as a transit station to Israel, the refugees had to present transit visas to Syria and Lebanon and an entry visa to the Mandatory Palestine in addition to a permit in their possession worth a sum of money equal to 300 Turkish liras at the time. After the conquest of France by Nazi Germany in June 1940 and the establishment of the Vichy government, the French Mandate authorities in Syria and Lebanon almost completely stopped granting visas to Jews from beyond Eretz Israel. The transfer of Polish civilians and soldiers to Palestine from now on focused on the port of Mersin where the Consulate General in Istanbul had a special representative to supervise the transit.

Britain, which controlled the Palestinian Mandate, was an ally of the Polish government-in-exile based in London, so it was important for the Polish side to consider it and coordinate all moves with it. However, it seems that there were some disagreements regarding immigration to Palestine and the Poles also worked to bypass the British, in order to allow Jews to arrive in Eretz Israel.

In a document dated July 2, 1940, archived in the AAN archives, about two weeks after France's surrender to Nazi Germany, the Polish consulate in Istanbul received a first report from the Polish Consul General in Beirut, Karol Bader, that France prevented Jews from crossing through Syria. The British, according to the report, tried to persuade the French to allow Jews to pass as Polish refugees. The consul in Beirut reported that there were also difficulties in the transfer of Polish military personnel to Israel.

On July 16, 1940, Rychlewicz sent the following message to the Consul General in Beirut: "Recently, the French consulate in Istanbul has completely stopped issuing visas to travel through Syria to Palestine. This caused a very difficult situation in Istanbul where there are about 100 former military personnel and are a larger number of civilian immigrants, most of them Jews, with certificates for Palestine.

"These people, due to the attitude of the French authorities, must remain in Istanbul under threat of deportation. I ask you to contact the French authorities in Syria and to get permission for the passage of Polish citizens through Syria to Palestine. My office pledges that none of them will stay in Syria. To better illustrate the difficulties arising from the position of the French consul, I inform you that a transit visa has been rejected to our diplomatic courier."

In a telegram dated August 13, 1940, the Polish Consul General in Tel Aviv, Henryk Rozmaryn - a lawyer, journalist, politician and enthusiastic Zionist activist – reports to his colleague Rychlewicz in Istanbul on the arrival of Chaim Barlas, a member of the rescue committee. "Please help him with his work", he writes.

Along with the problems with the French, a controversy erupts between Polish diplomats and the military attaché in Ankara. The attaché complains that the Polish government is evacuating Polish Jewish refugees from Romania instead of evacuating Polish soldiers stranded in Yugoslavia, who were to be brought to the Middle East before being captured by the Germans. According to him, the Polish embassy in Bucharest which created the list of evacuated people gave priority to "rich Jews" instead of dealing with Polish soldiers.

On June 28, 1940, the military attache writes to the "General," apparently General Władysław Sikorski, the exiled prime minister and the commander-in-chief of the Polish army, that Turkey refuses to grant asylum to a large number of Jews. This occurred after an intervention by Ambassador MichałSokolnicki, who sought asylum for those who were in danger for political reasons and tried to obtain visas through Turkey. The annex also reports that there are problems with Syria in the transfer of Poles by sea from Alexandra to Haifa.

On August 16, 1940, the military attache wrote: "The first transport from Mersin to Palestine left with 30 officers and 470 soldiers. On September 15, 1940, he reported a third transport involving 10 officers and 191 soldiers who had left for Palestine. 31 were sent to Cyprus. "The transport point in Istanbul is empty," he writes.

However, on September 19, 1940, the Polish military attaché complained to the General Staff of the Military Forces based in London: "I report that the chaos associated with the evacuation (soldiers) to Cyprus continues. Instead of sending Poles who are in political danger, the embassy in Bucharest sends Jews. In one transport they were sent at the expense of the state even though they have thousands of dollars in cash.

"Officers in Hungary and Yugoslavia are really in danger of being forcibly returned (to occupied Poland) while wealthy Jews from Romania move to Cyprus even though the British government has asked not to send Jews. The result will be as follows: the British will refuse to host more refugees and as a result Turkey will close its borders. Please issue a directive to the Cypriot Commissioner that the issue of transport is up to the decision of the Embassy and Military Annex in Ankara and not Bucharest. It is an egotistical act that endangers many of the officers with the rights to be evacuated."

On September 21, 1940, the Chief Military Headquarters of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in London finds a solution - persons in political danger will be given priority in evacuation. People who are not in political danger will not be evacuated. Do not evacuate people who have a lot of cash at the expense of the state. The term "political danger" in this correspondence was a term associated only with members of the Polish army, including Jews, but not with most of civilian refugees, also including Jews. Jewish civilians could still, however, travel to Turkey using their own resources.

A 1942 document sent from Ambassador Sokolnicki to the government-in-exile in London states: "A report states that between 1939 and 1942 more than 5,000 civilian [Polish] refugees passed through Turkey. Today, the total number of refugees in Turkey in Istanbul does not exceed 120." Among the citizens evacuated to Israel were also non-Jews although according to many documents they represented a tiny minority.

"To the best of our knowledge, anyone who received the documents issued by Consul Rychlewicz survived and, to my knowledge, Turkey, which by the way in 1939 had bravely refused to close the Polish Embassy and Consulate General, did not oppose this rescue operation" said Ambassador Kumoch, "We have so far identified 431 names, but Sokolnicki's cable suggests we are rather talking about a few thousands, not hundreds. What interests me a lot is the role of Ambassador Sokolnicki in the whole 'affair'. There was definitely an exchange of letters between the Embassy, the Consulate and Chaim Barlas, and the fact that Consul Rychlewicz left his fake confirmations in the archive suggests the operation was known to the government."

Wojciech Rychlewicz – the protagonist of the rescue operation – was born in 1903 in an area that is now part of Belarus. When the Bolsheviks came to power, he moved with his family to Latvia, where he remained until 1919. When the Bolsheviks attacked there as well, he fled to Warsaw and joined the Polish army at age 17 and participated in the Polish-Russian War. In 1920 he moved to Vilnius and began preparing for the matriculation exams, which he passed in October 1923. He thenenrolled at the Technical University of Vilnius, where he studied water engineering.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!

His appointment as an annex to the Polish Consul General in Istanbul in 1936 was apparently related to his service in Polish military intelligence. Like with many intelligence representatives, his CV between his foreign appointments is nearly empty – the same was a feature of Consul Rokicki, widely believed to be one of the members of so-called Dwójka, pre-War Polish military intelligence. We know only that in his student years he joined "Arkonia", a powerful student organization, one of those who accepted candidates regardless of their religion and ethnicity.

In 1937 Rychlewicz was appointed head of the consulate, though not officially appointed consul general. He held this position until 1941, when he also made his way from Mersin to Mandatory Palestine, where he joined the Polish Army.

Rychlewicz's granddaughter, Anna Whitty, MBE, does not know what motivated him to rejoin the army and what exactly he did in Israel. "The family used to say that he simply followed my grandmother around. She was a director at the Ain Karemschool in Palestine. When I think about it now, it is shocking how big our gaps of knowledge are about a time they didn't like to talk about. Or maybe I was simply too young."

Rychlewicz, ranked Captain of the Polish Armed Forces,probably fought in Italy. In1946, after a brief stay in occupied Vienna, during which time he was the army's focal point for dealing with Polish refugees, he moved with his wife to London, where he lived to the end of his life. Like many members and officials of the Polish government-in-exile he refused to return to Poland, which by 1944 fell into the hands of the Communists.

"Recently," says Whitty, "we found that my grandparents' personal belongings and documents were for reasons not yet clear, in the hands of a friend of my grandmother's friend, who lives in Texas. One of these screens is my grandfather's guest book."

"The first signature on it is dated May 7, 1938. These are mainly guests who have been on private visits. Sometimes they are difficult-to-decipher signatures, sometimes well-known figures such as the poet Jerzy Jankowski [from Aug, 31, 1938], and the famous Jewish violinist Bronislaw Huberman [from Jan. 20, 1939]. With the rise of the Nazis to power in Germany and the expulsion of Jewish musicians from German orchestras, Huberman became active in the public struggle against Nazi Germany and German orchestras that expelled Jews; instead of immigrating to the United States, where he could have had a successful career, he moved to Eretz Israel, where he founded a philharmonic orchestra. Many of its musicians were Jews from German occupied countries. Thus Huberman saved the lives of several dozen of them and their families. Huberman was one of the initiators of the boycott of Richard Wagner's works after the Kristallnacht pogrom."

"The guests mostly relate to the wonderful time they spent with my grandparents," Whitty continues, "after the outbreak of the war there are fewer signatures, but the style changes to immense appreciation. Here is one example: "Dear Sir and Madame, please believe me, as a writer I don't know what to write when I am really grateful and very moved by someone's goodness and simple nobleness - as only: Thank you. Thank you. God bless. Istanbul, 12.9.1940 Marian Hemar."

Marian Hemar was not a man who usually found it difficult to express himself. A Jewish poet, playwright, comedian, and songwriter, born in 1901 in Lvov, he wrote some of Poland's most popular songs before WWII. He fought alongside the Poles in defending his hometown and in the War of Independence after the First World War, moved to Warsaw in 1924, worked in various cabaret shows, prepared hundreds of sketches for Polish radio, also with political content, and became famous as one of Hitler's sharpest critics.

His famous song "Ten wąsik ach ten wąsik" in which he mocked Hitler's look provoked an official protest by the Nazi German ambassador in mid-1939.

Shortly after the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, Hemar fled Warsaw knowing that the Gestapo was looking for him. He came to Romania and from there to Turkey and continued to the Middle East - either to Israel or to Libya, where he enlisted to serve in the Polish Carpathian Brigade during the siege of Tobruk, and in 1941 to Britain, where he became a very well-known figure in Polish exile circles.

"I was very excited to hear that my grandfather did so much during the war," Whitty admits, especially since he was emotionally involved in it not out of a desire to be a hero. The irony is that I run a charity and I received an of appreciation from the Queen for the work I did, my parents ran the Polish school here for 30 years. As a family, we continue to work for those who need help."

"I hope that at some point I can meet the descendants of the Lifeguard Consul," says Bob Meth, "I will emphasize to them that one of the most important principles common to Judaism and Christianity is that every human being was created in the image of God and it is clear to me that the Polish consul subscribed to this philosophy as well. And I would say that my greatest hope is that the descendants of the Consul would view him as a role model in their own lives and would teach the lesson of his heroism to their children as well."