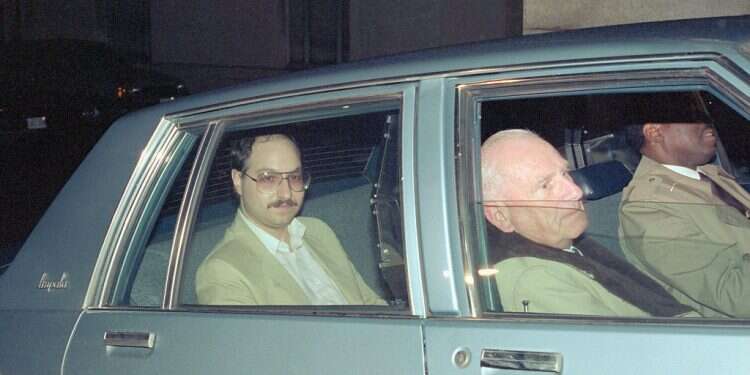

The 35-year saga that began with the arrest of the naval intelligence officer Jonathan Pollard on November 21, 1985, and continued with a plea bargain under which he was convicted for espionage on behalf of Israel, came to an end on Friday after his parole conditions were lifted.

The fact that Pollard was recruited during an era when there was already strategic cooperation between the Reagan administration and then-Prime Minister Shimon Peres was viewed in Washington as a betrayal of trust on the part of an ally and partner nation, which the US considered to be a regional asset in the Cold War.

The affair also gave tailwind and ammunition to senior US officials who were hostile to Israel, as well as fodder to the federal bureaucracy, who still had pockets of resistance from the early years of the relationship, when the two countries were not close.

The affair prompted the defense secretary to take a particularly vengeful posture toward Pollard and his Israeli recruiters. Then US Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger wrote a special memo on the eve of Pollard's sentencing in which he described him as a traitor (not just a spy) and claimed – without providing proof – that the information that he had shared with Israel was very likely to have reached the apartheid regime in South Africa, with whom Israel had close strategic ties at the time.

In the wake of that memo, the judge refused to accept the prosecution's recommendation for a normal imprisonment term and ruled that Pollard would serve a 30-year sentence.

The bureaucracy in Washington never forgave Pollard, or Israel, in the decades since his arrest, in part because of Israel's refusal to fully cooperate with the FBI, which only led to greater suspicions being cast on its conduct.

Quite a few senior officials in the US were convinced that some of the intelligence Pollard had given to Israel, especially regarding US satellite technology, ultimately made its way to the Soviet Union. That's why anytime US presidents were deliberating on whether to grant clemency to Pollard as part of a deal with Israel, they were met with fierce opposition by the intelligence community and even resulted in senior officials threatening to resign in protest, ultimately forcing the White House to backtrack.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

Although there is no question that Pollard's conduct was highly criminal, the sentence he received was disproportionate to a fault.

Other acts of espionage for a friendly nation resulted in much more lenient sentences. For example, Steven John Lalas, who passed information to Greek authorities was given a 14-year sentence and was allowed to go to Greece immediately upon his release.

The prosecution's insistence on exacting the most severe punishment from Pollard was even more apparent after CIA commission concluded that his actions did not compromise US national security.

But his conduct compromised the trust between the two nations to a major degree, not just between the US and Israel but also between the White House and the Jewish community, as it once again gave life to accusations of dual loyalty.

One should not discount the Israeli government's misconduct in this affair. The decision to recruit an American Jew as an intelligence asset was amateurish and wrong to begin with. Moreover, the Israeli government's refusal to take responsibility for its role, while simultaneously showing solidarity with him during public visits to his prison, only exacerbated the rift with Washington's bureaucratic establishment in the long run.

The lessons from this saga were presumably learned. One can assumet that Israel has since been guided by broad strategic interests rather than by tactical short-term gain in its relationship with the US.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories!