The assassination of Qassem Soleimani is a rare event that alters reality and renders everything that happened before it irrelevant. What's required now is almost a complete reassessment of all previously held assumptions and conventions.

It was, by a wide margin, the most significant assassination ever carried out in the Middle East. It is far more important than the assassinations of Osama bin Laden or Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Bin Laden was perhaps more famous that Soleimani, but eliminating him was mostly a matter of revenge. When he was killed he was the head of an organization in decline, whose past was far greater than its present and future. Baghdadi, too, was mostly a symbol of an organization whose future was already behind it.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

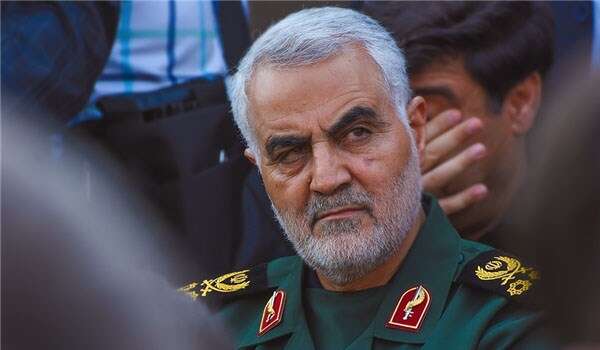

Soleimani, on the other hand, was a superstar. That's how he felt, and it's how he behaved. Very few people have had such a dramatic influence over the region in which they live. Far fewer have done so from a position other than head of state. Soleimani was one of these: His fingerprints were strongly felt wherever he went.

Soleimani was exceedingly talented, very charismatic, goal-oriented, and blindly loyal. He performed his duties – exporting the Islamic revolution beyond Iran's borders – with great success, far surpassing the wildest dreams of his masters. He was a combination of military strategist extraordinaire and seasoned politician, who was able to exploit the turbulence in the region (primarily the Arab Spring) to establish robust power and influence.

Alongside his clout inside Iran – the direct result of his close personal relationship with Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who viewed him as a son – Soleimani became one of the most important figures in the region. He was far more important than most heads of state, welcomed by some but feared by most. He helped install governments in Yemen, Iraq, and Lebanon, saved the regime of Bashar Assad in Syria and profoundly affected all countries and territories – from Yemen and Afghanistan in the east, to Lebanon and Gaza in the West. His influence reverberated far beyond the region, however, with the terrorist infrastructures he established in five continents – ready to be activated on the day of reckoning, which could be imminent.

Nasrallah and Assad are in shock

From the Israeli perspective as well, Soleimani was, by far, public enemy number one. He was the person most responsible for turning Hezbollah into a guerrilla army with more than 100,000 missiles, rockets, and elite commando units. He funded Palestinian Islamic Jihad (and to a lesser extent Hamas) in Gaza, and masterminded the plan to establish an Iranian presence in Syria to function as yet another active front against Israel.

Israeli leaders, on several occasions, toyed with the idea of taking him out, according to foreign reports. In 2008, when Hezbollah military chief Imad Mughniyeh was assassinated in Damascus, Israel could have killed Soleimani along with him, according to foreign reports, but because the operation was a joint Israeli-American effort the White House didn't give the green light and his life was spared. Since then he has been spotted sporadically in the northern sector – sometimes in Lebanon, sometimes on the Syrian Golan Heights – inspecting the situation on the ground with his people, who revered and feared him alike.

We can assume that Soleimani believed Israel was tracking him, but fear was not among his main character traits. Khamenei would refer to him as "the living martyr," due to his exceptional courage and willingness to risk death for the sake of the objective. Despite his lofty status, he took pains to visit his men in the field, see the situation with his own eyes, and influence developments. He was the patron, financier, and mentor to so many forces in the region, mostly negative, that most of them are likely feeling orphaned at the moment. Hassan Nasrallah saw him as a brother, and for Syrian President Bashar Assad he was a guardian angel. Without him, the reality for both these men is now far more complicated.

Soleimani's colossal importance notwithstanding, however, his assassination is dramatic because it signals the return of the United States to a position of regional influence. There had been considerable concern in recent months, among the Middle East's saner and more moderate actors, that American policy – specifically its repeated restraint over a downed drone, attacks on oil tankers in the Persian Gulf and oil production facilities in Saudi Arabia, together with its withdrawal from the Kurdish region in Syria and its supposed intention to leave Iraq – was emboldening the negative axis spearheaded by Russia and Iran.

Soleimani, who interpreted this as weakness, decided to start nipping at the Americans' tail. Their presence in Iraq impeded his plans to establish a contiguous land corridor from Iran, via Iraq and Syria, to Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea. Through the Shiite militias in Iraq, which he funded and trained, Soleimani recently ordered a string of attacks on bases and facilities housing US soldiers and defense contractors. He had also hoped these moves would divert the Iraqi public's criticism of Iran's presence in Iraq toward the United States.

A chance to renew negotiations

These provocations, which culminated in the coordinated storming of the US Embassy in Baghdad last week, cost Soleimani his life. He didn't expect it, nor did anyone else: There isn't an actor in the region, including Israel, whose proverbial jaw didn't drop to the floor upon hearing of his untimely demise. It wasn't just extraordinary on the scale of familiar responses and counter-responses in the region. By assassinating Soleimani, Trump invented a new scale, whose effect resonates far beyond the borders of the Middle East and the Persian Gulf.

The Iranian reaction to the assassination was predictable: shock, followed by threats of revenge. We need to take the Iranians seriously: They are a bitter, determined, and capable enemy, and will likely endeavor to send Americans home in flag-draped coffins, also to influence American public opinion in an election year. Soleimani, as stated, had planned to do this regardless.

The Iranians, though, are not suicidal. They will choose a painful target, but won't risk pushing the Americans over the edge again, certainly not amid a severe economic crisis and harsh internal strife (among other things over Soleimani's activities, which have cost billions of dollars at the expense of the struggling Iranian people).

In essence, this could be an opportunity to bring Iran back to the negotiating table to secure a better nuclear deal. It could also be an opportunity to formulate a deal among superpowers to remove Iran from Syria, and to also encourage more moderate behavior among certain leaders – from Pyongyang to Ankara and Moscow – who erred in thinking the US is afraid or has lost interest in leading the world.

In the current state of affairs, Israel is wise to sit on the sidelines. None of Soleimani's subordinates in Syria or Gaza are likely to respond by firing rockets, but generally speaking, this is an American event and better it stays that way. Israel needs to continue focusing on its own wars and enemies, who have lost their most significant player. In this regard, the world without Soleimani is a much better place.