A family Torah scroll that was saved from destruction in Ansbach, Germany during Kristallnacht was handed over to the Yad Vashem memorial and museum by the granddaughter of its owner.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

The Torah scroll belonged to Dr. Ludwig Dietenhofer, "an industrialist who was active in Ansbach community life," according to Yad Vashem. Dietenhofer, who lived alone at the time because his children had all moved out of Germany, "held several public positions in the city, including as a member of the city council and head of the Jewish Community Committee."

Dietenhofer, a Zionist, planned to move to British-held Palestine and help build an independent Jewish state, and ultimately made it there shortly after Kristallnacht, or "Night of Broken Glass," when Nazis terrorized Jews throughout Germany and Austria.

During the fateful night on Nov. 9-10, 1938, Nazis killed at least 91 people, burned down hundreds of synagogues, vandalized and looted 7,500 Jewish businesses and arrested up to 30,000 Jewish men, many of whom were taken away to concentration camps.

Dietenhofer, who realized even before that night that Nazi persecution of the Jews was escalating, made sure that the Torah scroll would be spared and taken to a safe place several days in advance.

"On 27 October 1938, a tear gas bomb was thrown into the synagogue in Ansbach during prayer time, and the congregants were forced to stop praying," Yad Vashem noted on its website. "In November 1938, shortly before Kristallnacht, Ludwig was summoned to an urgent meeting with the Ansbach Chief of Police. The police chief, a friend of Ludwig's, warned him about the approaching riots, the anticipated synagogue conflagrations and physical violence, and urged him to leave the country as soon as possible."

Dietenhofer accepted that advice and took the Torah scroll, which had been donated to the synagogue by his family and used for multiple generations.

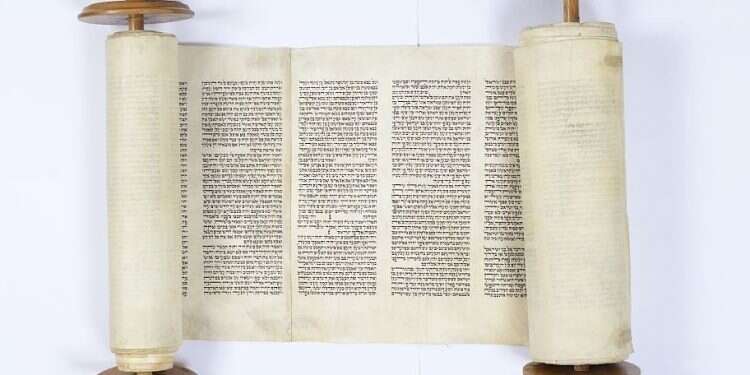

"The Torah scroll was bound with a decorative "wimpel" (Torah binder) that had been donated to the synagogue in 1840," Yad Vashem said.

His mission to save the synagogue's scriptures was no small feat. "On the night of 9-10 November 1938, Kristallnacht, the mayor of Ansbach was ordered by the Nazi headquarters in Nuremberg to imprison the city's Jews, to vandalize their apartments, and to torch the synagogue," the Holocaust memorial said, noting that the mayor instructed partially defied the order and instructed local Nazi paramilitary forces not to hurt the Jews. He even made sure that "a box of prayer shawls and ritual artifacts was taken out and brought to the police station for safekeeping."

But despite this apparent effort to save the Jews, the mayor did play a role in vandalizing Jewish property: "He sent two people to set fire to the synagogue, they smashed up benches and burned them together with Torah scrolls and other Jewish books. Immediately following his order to burn the synagogue, the mayor sent the fire brigade to put out the fire. The flames scorched two pillars, a curtain, Torah scrolls, two Torah ark curtains from the early 18th century, and two chandeliers."

According to Yad Vashem, "most of the Jews who had been detained as per Nazi orders were released the following morning on the mayor's instruction, including Dietenhofer."

Dietenhofer then left Germany for Austria, and passed through Hungary, Russia, China, South Africa and Gibraltar before reaching Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine) about a year later. He gave the Torah scroll and wimpel to his children when he immigrated.

Dietenhofer is buried in a cemetery at Beit Hashita, a kibbutz in northern Israel where his son lived. His granddaughter Ruthy Baruch, recently handed over the Torah scroll and wimpel to Yad Vashem as part of the museum's effort to preserve personal items from the Holocaust period.

"This scroll has been passed on from generation to generation in our family, it is part of our history and means a lot to me personally," Baruch told Israel Hayom. "My great grandfather read from it, my grandfather read from it, and so has my father and his three brothers, as did my grandson. For many years, this scroll was at the kibbutz, and we took it with us when we moved. But we decided that giving it to Yad Vashem was the right thing to do because it will now be preserved and put on display."