A recent survey of Israeli students revealed that only 5% think that the 1973 Yom Kippur War was a victory. A large part didn't even know what the Yom Kippur War was, or what happened.

These numbers horrified the members of the nonprofit Yom Kippur War Center. It made clear what they had already suspected – that the worst war in Israel's history was being forgotten. That the price paid in it was being taken for granted, and that its legacy was non-existent, and that if the story of the war – and their own stories – weren't told now, it would never be told, as the generation who fought it is dying off. The current General Staff of the IDF doesn't include a single general who enlisted in the military prior to 1973, and only 12 currently serving MKs fought in it.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

A group of Yom Kippur War veterans is trying to change the narrative and inculcate a different kind of discourse and a more accurate memory of what happened here 46 years ago. Supposedly, it should be obvious; in actuality, it's a Sisyphean and very Israeli task in which common sense fights bureaucracy. Every citizen should hope that intelligence and justice beat the functionaries to allow the right thing to be done, even if it's very late in coming.

Only two hours before

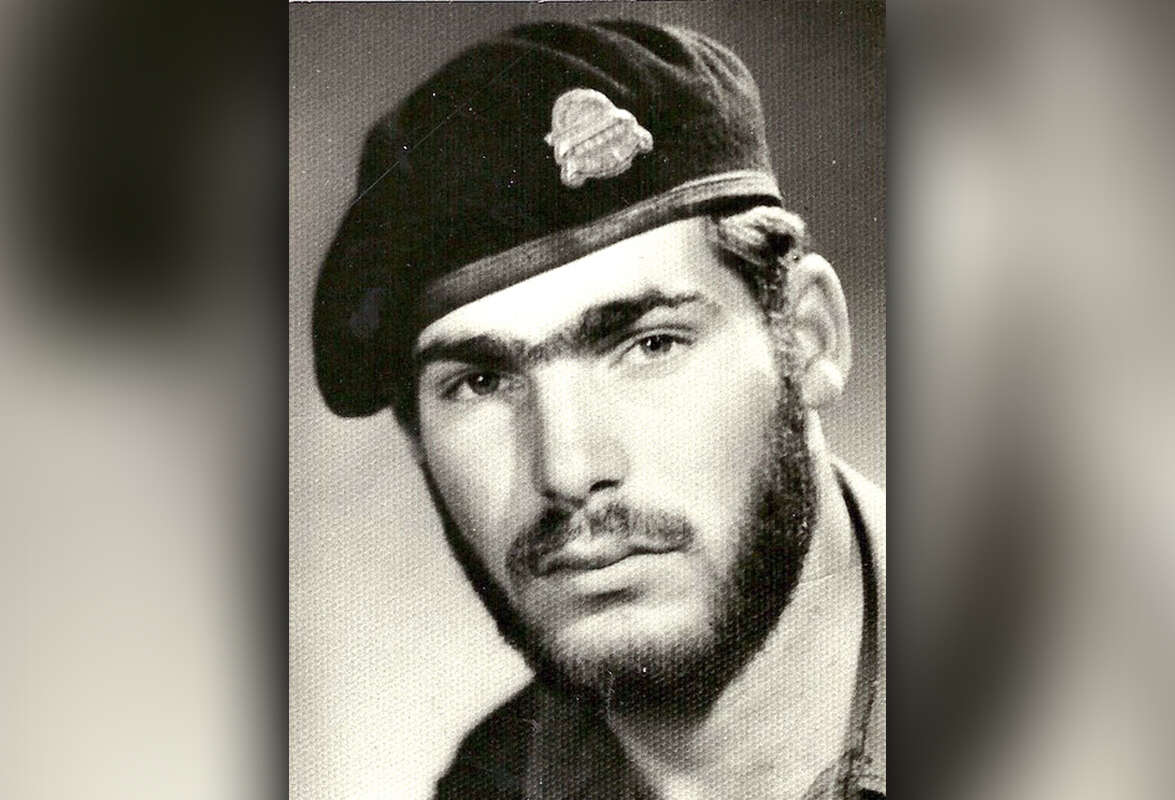

Rami Swet is a story. A personal story, a family story, the story of a generation. His parents, Zvi and Ruth, made aliyah from Europe before World War II. They lost their entire families in the Holocaust and both enlisted in the British Army – Zvi was a commando, Ruth was a nurse. They met in a hospital after Ruth was called in to translate for a wounded Israeli, and they married after the war. They settled down near Negba and built a ranch.

Later, the parents moved on to the new Afeka neighborhood in north Tel Aviv. After the 1967 Six-Day War they moved to Nuweiba in Sinai, where they owned a gas station. They had five children, three boys and two girls. All the boys served in the IDF Armored Corps and the girls went to the Medical Corps and army human resource management.

The Yom Kippur War found the Swets scattered in various locations. Micky, the eldest son, had finished his time as a company commander and had been sent to university at the army's expense. He was with his wife, who was about to give birth. Yair, the middle son, was a platoon commander in the 77th Battalion under Avigdor Kahalani [who would later serve as IDF chief of staff] and just about to be discharged. Rami, the youngest son, was a newly-minted officer and was serving as a teacher in the course for tank commanders.

"The eve of the war, all three of us were called up to the front," Rami recalls. "Yair's battalion, which had been in the Sinai, was moved up to the Golan front. Micky ran to the emergency supply unit and left for Sinai. I was called up with an ad hoc battalion from the Armored Corps training school to the Golan Heights, and we got to an area we weren't really familiar with. We got maps just two hours before the war broke out."

Rami's war didn't begin when the siren sounded, but with four Syrian fighter jets that were on their way to the Israeli command in Nafakh on the Golan Heights, and attacked him and his comrades, as well. "I knew that Yair was in the area, too, but I didn't know exactly where. Only later I learned that when I was near Hermonit and north of it, he was 500 meters [550 yards] away from me in the Beqaa Valley."

Rami's battalion was trying to stop Syrian incursions in the area between Hermonit and Tel Varda, but because they were an informal, inexperienced battalion unfamiliar with the territory, it fell apart as quickly as it had been formed after the commander and deputy commander were both killed.

"I was wounded on the fourth day of the war. The first time was at Hermonit from shrapnel, and then when the tank was hit – a wound that caused me to lose my vision temporarily," Rami says.

At the hospital, he met other wounded. Naturally, the conversation centered around their experiences, and one of the wounded next to him said his company commander had been killed. Someone asked what the commander's name was, and the wounded man answered, "Swet." That was the first time Rami learned that his brother Yair had been killed, but he refused to acknowledge it. After he was released from the hospital he was sent back to the Golan Heights. At Nafakh, he met his brother's deputy and realized what had happened.

Q: How was Yair killed?

"He was killed on Oct. 7, the second day of the war, in battles to stop [the Syrians] on the Golan. The team that was in front of him on the slope was hit, and the soldiers jumped out of the tank. Yair left the turret and got down to pick them up, and during the rescue he took a direct mortar hit and was killed. His team was traumatized and abandoned the tank because they thought the tank had been hit, too. They got back to it only three hours later. It was still running, with Yair's body inside it, and they got him out."

Yair Swet was posthumously awarded the Medal of Distinguished Service for his part in the battle. The background for his medal states that "He hit enemy tanks at close ranges of 200-500 meters, and caused the enemy heavy losses. As the battle continued, one of his company's tank was hit, and the crew was seen jumping out. Lt. Yair Swet approached the crew to see what had happened, and when he stopped, he was hit and killed. Lt. Yair Swet served as an outstanding example of courage and coolness under pressure for the entire company, and inspired the soldiers to hold their ground and continue fighting."

Rami saw all this unfold from a few hundred yards away but didn't know that Yair was part of it. He also didn't know that his older brother Micky had been wounded in battles in Sinai.

"We rolled down to Sinai, to the northern edge of the [Suez] Canal," Micky says.

"When we got to the highway, I turned to the west to identify where the Egyptian enemy was and approach them. Our tanks and armored vehicles that had been hit were burned and blackened at the side of the road, and immediately we realized that this war would be very, very different. An APC carrying soldiers on compulsory service came in my direction and I spotted the commander. I asked him, 'Where are our forces, and where's the enemy?' His answer was tough and dry: 'Our forces are done – everything ahead of you is just the enemy.'"

Micky took part in the large-scale offense, which failed, continued southward, and then was sent back to the main front.

"The battle started when we were under cover, and later on we ambushed the target. The battalion commander, with two companies, was fighting on the left flank of an Egyptian infantry force that was entrenched and aided by tanks. I was fighting on the right flank at short range, facing gunfire, grenades, and risking being run over by tank treads. Besides the fierce fighting, the radio informed us that all three platoon commanders had been hit, myself included. When the brigade commander's tank was hit, he handed command of the battalion over to me and got it out of the way."

"Because my tank had been hit too, in the motor, and black smoke was coming out, I told the battalion to move on while I marked the route as a smoke column. When the battalion was rescued, my team managed to put out the tank fire, and all the wounded were evacuated to a makeshift battalion regroup point."

Micky himself, who also received the Medal of Distinguished Service for his conduct in battle, was taken to Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem, where he read the human resources report about the identities of the wounded, including the name of his dead brother, Yair, and his wounded brother, Rami.

How to tell the parents?

At Nafakh, Rami was given Yair's personal effects: a book of phone numbers, his bullets, and a few other things. He wanted to go back to the fighting, but was denied for fear his family would sustain two casualties. He also learned that his older brother had been wounded and went to visit him in Jerusalem. "I tell him what happened to Yair, and we decide that we have to tell our parents."

Micky couldn't leave the hospital, so Rami went to his parents' house alone and informed his mother and sister.

"My mom had two requests. One, that even though 10 minutes earlier I'd told her she had lost a son, that I go back to the front, because 'I wouldn't be able to look my friends in the eye,' and second, that before I did that, I find my father and tell him."

Rami went to Sinai, where his father had remained to keep the family gas station running for the war effort. "Dad made a tear in my jumpsuit, gave me a hug, and said, 'Go to the front.'"

Rami did as his parents told him to, went back to his original unit from the tank officers' training course, and continued to fight in Sinai as a tank platoon commander as far south as Suez.

Q: Your parents were tough.

"It was a different generation. Mom refused to come to the medal ceremony to accept Yair's. She wrote that medals weren't for the parents. I always argued that, sadly, only soldiers get medals and not mothers."

Yair was given a battlefield burial during the war. Only two months after the war was over did the family first visit a cemetery, and on the one-year anniversary of his death, Yair was reinterred on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, "because our parents had been thinking about going to live in the Jewish Quarter, and wanted to be close to him."

Rami's father died 20 years ago. His mother died eight years ago. In the 2006 Second Lebanon War he was forced to bring her sad news again and report that her grandson, his sister's son, had died. "She said that she hoped my sister would be able to cry, which she hadn't."

Q: Your parents didn't cry?

"They cried in secret. With the door closed. My father was very bitter about Yair being killed. He saw the government and the army as traitors who sent children to be slaughtered like lambs."

Q: Was he right?

"Professor Asa Kasher said at the founding conference of our group that the country has an obligation not only to defend its citizens, but also to defend its soldiers. Today it's clear to everyone that things could have been done differently, and that we were asked to stand on the front in unrealistic conditions that dictated that we would have 2,673 casualties and over 11,000 wounded in the war."

'More is still being kept secret'

Despite the grief and the anger, Micky and Rami continued to serve in the army. Micky served as a battalion commander and later on as a division commander in the reserves, and Rami went on to two battalion commander roles – including the first battalion of Merkava tanks – until he was discharged in 1983. After that, he remained a reservist for another 20 years. "It was clear to us that we need to be part of the [post-war] rehabilitation," he says.

But the war has never left him. Two years ago he decided, along with a group of friends, to establish the Yom Kippur War Center, a nonprofit organization that would work not only to keep the memory of the war alive, but also to teach its legacy.

"It was the most significant event in the history of the country since independence. A war that threatened its existence, in which the entire population took part," he says.

Q: Why now?

"Because our generation has undergone a process of internalization and silence, and like our parents and grandparents didn't want to talk about the Holocaust, it didn't talk, either. We have a moral obligation to pass it on."

The organization plans to build an active center that will focus on four different goals: making information accessible, telling the story of the war, documentation and research, and serving as a center to commemorate heroism in the war. They hope it will be recognized as a national heritage site, like Ammunition Hill. The city of Netanya has already allocated land for the center, which will be built at an estimated cost of $30 million. The organization intends to promote a cabinet bill to expedite the processes to build the center and have it recognized as a heritage site, with the hope that in the future all IDF soldiers and schoolchildren will visit it on organized trips.

The group now boasts some 3,000 members, most of whom fought in the war. Rami Swet is the chairman, and he has set a goal of starting construction this coming year, with a projected opening date of October 2023 – exactly 50 years after the war broke out.

"This war hasn't gotten the respect it deserves. Even today, more about it is secret than is known. We are about to petition the High Court of Justice to force the government to release material about the war," he says.

Q: Like what?

"The Agranat Commission Report dealt with only one point – who was responsible for the [war's] failures. It didn't research the war. Most of the relevant documents are still classified. It's absurd – if I want to know what's happening in Iran, I turn on the news, but if I want to know what happened with the air force on Yom Kippur I get a file that is mostly redacted."

Swet says that the government has 23,000 documents on file that are waiting to be declassified, and that the IDF also has a wealth of information that is still secret.

Aside from the mission of commemoration, the group wants to change the way people talk about the war from the focus on failure to a discussion of heroism and victory.

"It's not that there weren't problems, but that's not the main thing. Take the data from the start and from the end. There's no army that could have turned things around and led to a victory like that. The army rose to the occasion, and the army isn't the top level of the government. The soldiers were the ones who won the war, and that's something we have to instill in people's minds. And that's even discounting that it was the only war that has led to a peace treaty."

Q: Why the urgency to do this?

"I wear three different hats: someone who fought and was wounded in the war; someone who was bereaved; and someone who now sees what is happening in the Israeli public. This event ended and was forgotten as if it was some minor episode in Israel's history."