Said Abu Shakra remembers how when he was a child in Umm al-Fahm in the 1960s and 1970s, Knesset elections would mainly result in disappointment.

"[Youth movements] Hashomer Hatzair and Mapam would initiate joint activities for Arabs and Jews, and the parties told us, let's think about what we want and dream of. But when the election was over, the dreams would end, too, at least until the next election," he says.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

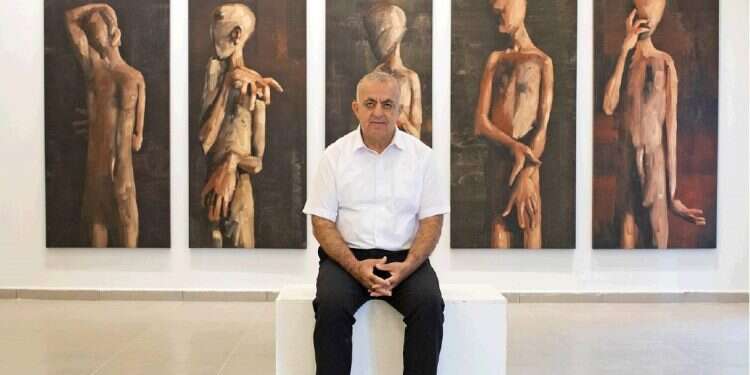

Fifty-two years later, at the end of a historic week of political involvement by Israeli Arabs, Abu Shakra is more sober. As the founder and director of the Umm al-Fahm art gallery, and one who is considered a leading figure in building bridges between Arabs and Jews, he has spent years on the Sisyphean task of encouraging the Arab sector to take part in Israeli civil life.

Although he is criticized for it, Abu Shakra insists on maintaining close ties with the Israeli establishment, and in turn, receives its support.

"They know that I'm fighting for funding for something that's important to all of us. There's no [public] school that doesn't get money from the Education Ministry," he says.

He says that most of his critics come from the Arab and Palestinian world outside Israel.

"When I tried to find US donors for the gallery and I'd show them catalogs, some would ask me why they were written in Hebrew, too, rather than Arabic only? I told them I live in Israel, study here and eat here, so it was obvious that I would know the language. The funding from Israeli institutions reflects my real battle for rights."

Abu Shakra doesn't ascribe the Joint Arab List's electoral achievement – 13 seats – to its politicians, but rather to the Arab public.

"The parties didn't say anything. It was the voters who told the politicians – we want political involvement, and want to be part of the decisions, the debates, and the future of this place. The Arab public wants to see itself an inseparable part of what happens in Israel."

Q: Would you like to see the Joint Arab List join the government? Get a ministerial portfolio?

"I always wanted to see a minister from the Joint Arab List or from an Arab party. Today I'm saying what I've always said – if you don't want to be part of the solution, you'll always be part of the problem. And to be part of the solution you need to be on the inside, work, do things, and make decisions. You can't be part of all that if you stay on the sidelines."

Abu Shakra thinks that the reality is changing.

"Today, no one can shove the Arab public aside and ignore its existence. It's a very important community in Israel, one in which changes are constantly taking place. It's becoming more varied and more educated. We aren't satisfied with being part of the final product. We want to take part in the process of development, which will eventually benefit us, too."

Q: So is the Arab sector conducting some introspection?

"We are learning from the mistakes of the past. We've never taken responsibility for our failures or for our future."

'A cup of coffee solves anything'

Last month, Abu Shakra, born in October 1956, was awarded the Shulamit Aloni Prize for artists with links to Arab culture and the Arabic language who promote human rights, social justice, and coexistence. He was born and raised in Umm al-Fahm, in a family who has been here for generations. He studied art at Beit Berl College and in addition to his artistic endeavors served as a police commander and did outreach with youth at risk.

He comes from a prominent artistic family. His older brother Walid, who passed away a month ago, wrote mainly in English. His middle brother Farid is a noted painter. His cousin Assam, who died of cancer in 1990 when he was only 29, is considered a groundbreaking artist. The gallery he founded in Umm al-Fahm 25 years ago now includes four floors, including 1,500 square meters of exhibit space, archives, and research rooms, as well as modest accommodations for artists showing at the gallery.

When he shows the work at the gallery, which now represents Jewish artists as well, such as Efrat Galnoor or Dubi Harel alongside Palestinian artists like Issam Darawshe and Saher Miari, Abu Shakra is as excited as a boy.

He proudly shows a piece by "the artist-builder" Miari, which features a concrete wall that looks like it was removed from a bomb shelter alongside buckets of cement rubble. The piece expresses "the lack of security of the Palestinian, who builds shelters for Jews."

He jumps to a piece by Micha Ullman, which features a mound of packed, dark brown earth in the shape of a volcano, sitting on top of a glass.

"I brought Micha this earth from the lands of the village al-Lajjun, where the Megiddo Regional Council now sits," he says.

"Once, all this land belonged to people from Umm al-Fahm and they would go out to work it. In 1948, when there was a battle there, Mom waited for Dad and made him food. When people started to flee en masse, the only thing she was worried about was whether Dad's food would stay warm, so she wrapped it in a blanket and left it in a corner, thinking that they would be back in an hour or two to eat. But they never went back. When Micha put this piece on display, we said that one of its messages is that even though the land around it is shaking, there is nothing a cup of coffee can't solve."

He was inspired to open the gallery in Tel Aviv after the death of his cousin Assam rocked the family.

"Assam, who was five years younger than me, was known for his paintings of cactuses, which became a recurring, obsessive theme in his work. After he died, the Helena Rubenstein Pavilion in Tel Aviv put on a solo show of his work, and people came by bus from Umm al-Fahm to see it. I thought, why not in my town? I had to wait for Tel Aviv to show my work, and that bothered me. So I decided to open a gallery."

The gallery, which is run as a non-profit organization and represents Palestinian, Jewish, and international artists, plays a major part in community life. It hosts ceramics workshops and a photo archive of the residents of Umm al-Fahm and Wadi Ara that includes some 600 videotaped interviews, 800 photo portraits, and thousands of images of landscapes, homes, and other places in Umm al-Fahm and Wadi Ara that were collected all over the world.

'We're still a marginalized society'

Abu Shakra says that his main goal is that "the gallery not display my weakness, but my pride – and I can't be a proud person if I'm weak or a victim. I told myself that the gallery would prove that I'm not another victim in Israel, but someone who can carry himself with pride and personal strength. The way I see it, Jews no longer want to pet the poor Arabs and the Arabs aren't willing to be wretched and weak. Those who wanted us to be water carriers now see us as doctors and lawyers. Both the Jews and the Arabs agree that if we treat each other as equals, change can come."

Q: Some see that as less legitimate, such as your cousin, Sheikh Raed Salah, leader of the outlawed Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement.

"I don't want to defend him, but his trial has been going on for four years, and I haven't seen or heard him calling for the destruction of Israel. There are various interpretations to what he says. What is a shahid [martyr]? Anyone who falls in battle is called a shahid, and so is anyone who is killed in a car accident on his way to work. I think the Arab population in Israel is under too much attack. Our leaders are subject to very crude treatment. Long ago, we were targeted, and if that target is erased, things can work out."

Q: It also has to do with the vast differences in how violence is handled. 68 people have been murdered in the Arab sector since the start of this year, seven this past week. How do you 'erase the target' when it comes to an issue like that?

"Violence is Arab society is a very serious problem, but it always has been – it's just that it was ignored for years. It was easier to say, like [TV host] Yaron London did, that Israeli Arabs are 'wild' or decide they were born that way instead of saying that the role of society is to place boundaries and educate the "feral."

"Israeli law enforcement doesn't put enough emphasis on giving Israeli Arabs boundaries. It's unacceptable that a person who owns an illegal weapon and can kill people with it is released on recognizance. Murders cannot go unsolved. We're still a problematic marginalized society, one that is poor and orphaned, so the solution people find for themselves is to become henchmen for criminals and even hit men. Israel, as a state, has to wield an iron fist and strike a harsh blow against anyone who breaks the law and behaves violently."

Abu Shakra's next big dream is to open an art museum in Umm al-Fahm. Plans are already underway.

"It will combine free art for the entire population and display high-quality art from the collection the gallery has built up. The museum will be Israel's first home for Palestinian, Israel, and international culture.

"By nature, I'm an optimist who believes in the power of culture and art to overcome humans' emotional obstacles. Every person carries fears and hesitations, and I respect those. A meeting has the power to break down those fears and give people the sense of connection and respect.

"The gallery, and later on the museum, address problematic subjects at Israel's core. Because we address them correctly, the Jewish visitors who come are given a chance to look at me as an equal, with all that entails. To see me when I'm in pain and when I'm happy, when things are tough for me and I'm scared, and when I'm hopeful. To discover who I am."