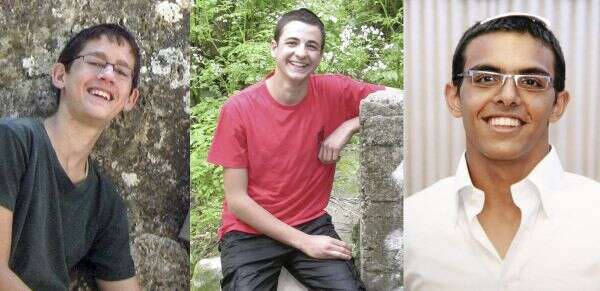

It was a national trauma. In June 2014, three Israeli teenagers were abducted after hitching a ride in the heart of Gush Etzion, and disappeared as if the earth had swallowed them up. For days, an entire country kept its fingers crossed that they would be found alive. Thousands of soldiers and civilians searched every inch of ground, and special units arrested any Hamas operative who might have been able to provide a clue to their whereabouts and help capture the kidnappers.

The searches continued for 18 days until the boys' bodies were found, almost by chance, near the Palestinian town of Halhul. Thousands accompanied them as they were laid to rest, but the drama wasn't over. For three months, the Shin Bet security agency, the IDF, and personnel from the Israel Police Counter Terror Unit continued to hunt the terrorists who had abducted and murdered the three teens. Meanwhile, Israel tumbled into Operation Protective Edge against Hamas in Gaza.

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

Five years later, the main players speak for the first time in the new film "Kidnapping in Real-Time," which will be broadcast on Israel's Channel 12 at 9:15 p.m. on Saturday. The film includes testimonies from the commanders of the mission that was doubly complicated – both in terms of the effort to find the boys and the pursuit of the terrorists, which ended in a dramatic operation in Hebron where the kidnappers were killed in a carpentry workshop.

It happened on Thursday, June 12, 2014, at 10:22 p.m. The kidnappers, Marwan Kawasme and Amar Abu Aysha arrived at the Gush Etzion junction in a stolen car that they had acquired ahead of time. They had been there the previous night, but hadn't found a likely target. So they went home and tried again the next night.

The kidnappers spotted an Israeli teen looking for a ride at the hitchhiking post at the entrance to Alon Shvut. That was Eyal Yifrach, 19. The kidnappers stopped, told him they were going to Ashkelon and beckoned to him to hop in. Two other teens, Gil-ad Shaer, and Naftali Fraenkel, both 16, stepped out from the post and joined the ride. All three sat in the backseat.

Shaer and Fraenkel, who were classmates at Yeshivat Mekor Chaim Yeshiva in Kfar Etzion, didn't know Yifrach. Immediately after they got into the car, the terrorists turned around and pointed a gun at them. Shaer managed to call the police emergency line and whisper, "We've been kidnapped."

The operators tried to understand what was going on, but they dropped the matter.

"They were sure someone was playing a prank," says Israel Police Supt. Shai Cohen, head of the emergency dispatchers department at the National Police Headquarters and a member of the investigative committee that probed how the emergency operators responded to the call.

"They tried to contact the [Shaer's] number, and when he didn't answer, they assumed it had been a prank call because a large percentage of the calls directed to the Judea and Samaria emergency line are pranks," Cohen explains.

Seconds after the kidnappers shot the boys, they turned the car around and drove back in the direction of the junction where they had originally picked them up. By the time an hour had passed, Shaer's parents had begun to look for him after he neither arrived home nor answered his phone.

"We called everyone we could, but the boy had vanished," says Shaer's father, Ofir. Shaer's parents reported him missing. Police went to Fraenkel's house to see if the boys were there.

"We were woken up at 3:30 a.m. by [the police] knocking," says Fraenkel's father, Avi.

"Police were standing at the door, looking for Gil-ad. I went upstairs to Naftali's room and they weren't there. It came as a 'boom.' When I realized that the phone had pinged in the Hebron area, it was obvious that the situation was bad," Fraenkel says.

The security establishment got involved only early the next morning. After consultations, a decision was taken to announce a "test of truth" – the code for a kidnapping.

"Right away, I realized this was something different," says Maj. Gen. Tamir Yadai, currently commander of the IDF Homefront Command, who at the time was the commander of the IDF's Judea and Samaria Division.

"I remember packing a bag and telling my wife that I had no idea when I'd be back," Yadai says. Like the rest of the people involved in the events that unfolded, it would be more than three weeks before Yadai was back home.

The searches focused on a ravine near Bayt Kahil. After examining the highway cameras and communication data, it turned out that the terrorists had stayed in that area after the abduction. The prevailing assessment was that they were holding the boys captive there, or had buried them somewhere nearby.

"We turned over every square inch. There's not a single home we didn't search, no point where we didn't dig," Yadai says, adding, "We hoped at least one of them was alive."

The working assumption was that the boys were alive, but the searchers' gut feeling said otherwise.

It was clear to the Shin Bet that it would take a miracle to find them alive. "Hamas in Hebron has a tradition of not leaving kidnapped victims alive," says Assaf Yariv, who at the time was head of the Jerusalem and West Bank district in the Shin Bet and oversaw the intelligence-gathering aspect of the search.

The feeling was bolstered when officials listened to the recording of Shaer's emergency call. Yariv was one of the first to hear it. He thought he could hear shots. Others in the Shin Bet situation room thought differently. Yariv asked Shlomi Michael, then-commander of the Israel Police Counter Terror Unit, to listen to the recording. Michael confirmed that shots could be heard.

For the first 24 hours, security forces had nothing to go on. Information trickled in slowly. On Friday night, Kawasme and Abu Aysha were already the prime suspects after security forces received a report that they had been seen in the vehicle used in the kidnapping. Special units raided their homes but found nothing. Other attempts to find the two were in vain. A few hours later, it was obvious to the Shin Bet that they were the kidnappers, but no one had any idea where they were or what the condition of the boys was.

The next decision was to work in two directions: field searches, based on an analysis of the route that the car took, and intelligence-operational work that would probe every report and every suspect. The search was named "Operation Brother's Keeper."

For days, there were no developments. The terrorists hadn't made contact to negotiate for the boys' release. "My biggest fear was that we would get to the kidnappers and kill them, and would never know what happened to the boys," says Yariv.

Only on Saturday, June 28, 16 days after the abduction, did a Shin Bet field coordinator who had joined the searches find Yifrach's glasses at the side of the road, in a place near the village Bayt Kahil that had been swept dozens of times already. A few yards away he found a pen and bloodstains. This was the first time the searches had turned up anything that brought security forces closer to either the teens or the kidnappers.

That night, Shin Bet personnel visited the Yifrachs' home to ascertain that the glasses found had belonged to Eyal. They wanted to find out where the glasses had been purchased, and the same night the owner of the shop was located. He confirmed that he sold glasses from that manufacturer.

The next day, Sunday, June 29, the three boys' parents were taken to the place of the kidnapping. They asked to meet with the soldiers who were searching for their sons so they could thank them.

"Instead, they thanked us," says Racheli Fraenkel. "They said they wouldn't stop looking until they found them."

Yadai remembers that meeting.

"People didn't go home [on leave] for weeks. There were soldiers who gave up their end-of-service vacations or decided not to visit their parents abroad just so they could keep looking. If there are moments that make army service worthwhile, this was one of them."

That evening, a solidarity rally took place in Rabin Square in Tel Aviv. Searches went on in areas determined by the Shin Bet based on evidence and intelligence. An analysis of the territory was conducted by people from the Kfar Etzion Field School, who had joined the search efforts a few days earlier. They pointed out mostly abandoned spots and wells where they suspected the victims, or their bodies, might be.

On Monday, June 30, the bodies were found in one of the locations identified, Khirbet Arnab, near Hebron. Searchers intended to look into a well, but after they discovered it to be empty, something caught the eye of one of the field school guides.

"There was a pile of dried bramble. It was obvious someone had piled it up," says Maj. Hani al-Quran, then a tracker officer with the Etzion Brigade. "The guide and the tracker spotted the brambles and saw a pile of rocks, dug a little, and then hit something. It was part of a body."

After all the bodies were found, most of the forces moved southward to Gaza, where an escalation was taking place that would turn into Operation Protective Edge. Although Gaza had been simmering in the previous weeks, the abduction and the search efforts heightened tensions. In Judea and Samaria, hundreds of Hamas operatives were arrested, including leaders of the organization and many terrorists who had been freed in the prisoner exchange deal for captive soldier Gilad Schalit. Hamas responded with rocket fire, and Israel launched counter-attacks until everything blew up into a ground conflict that lasted 50 days and saw 73 Israelis, a Thai foreign laborer, and 2,000 Palestinians killed.

As the operation was underway, security forces continued to hunt for Kawasme and Abu Aysha. "We arrested anyone who might have ties to them," says Chief Supt. O, who was then head of the combat branch of the Israel Police Counter Terror Unit. "The special forces alone carried out over 40 major arrests of people who were closely associated with them. It seemed to me that other than their first-grade math teacher, we arrested everyone."

Yariv, who directed the hunt for the terrorists, says that hundreds of people were arrested in the process of finding the kidnappers. "Every time we thought, now we're there, we'd find ourselves at an impasse. Among other things, it had to do them making no mistakes."

"They cut themselves off from the world as if the earth had swallowed them up," said Arik Barbing, who was head of the Shin Bet's cyber division. "They didn't talk on the phone, they didn't surf the net, they didn't send texts, and they didn't do anything different that would allow us to reach them."

The security establishment was familiar with the kidnappers: they had been under administrative arrest but were later released. There were hundreds like them in the Hebron area.

In mid-July, exactly a month after the kidnapping, the Shin Bet investigation led to an operation in east Jerusalem in which Hussam Kawasme, who owned the land where the bodies were found, was arrested. The interrogation was difficult. Kawasme played innocent and refused to admit that he had any connection to what had happened. Only after several days did he admit to leading the terrorist cell responsible for the kidnapping.

"He told us he approached his brother, who had been deported to Gaza in the Schalit deal, and asked him for money for a military operation. His brother sent him 150,000 shekels ($43,000) in cash through a female relative, and that money was used to buy the cars and weapons," Yariv says.

Hussam Kawasme told interrogators that the terrorists had planned to kidnap one Israeli and keep him hidden in a barbershop in Hebron where Marwan worked while they negotiated to release him in exchange for Israel freeing Palestinian prisoners. But after three Israelis got into the car, the kidnappers decided to murder them instead.

"They dropped the bodies at one end of the wadi and went into Hebron. Marwan got out of the car and went to Hussam, and Amar took the car away to burn it. Hussam and Marwan got into Hussam's car and drove together to bury the bodies on Hussam's land, and then Hussam dropped Marwan off in Hebron. There they went their separate ways," Yariv says.

The arrest of Hussam Kawasme didn't lead security forces to the murderers. The breakthrough came in mid-September as a result of a creative operation by a Shin Bet coordinator in Hebron. Police counterterror and Shin Bet personnel carried out a series of operations in Hebron, each of which yielded a little more information that led to progress. There was a concern that during the High Holidays, which were around the corner, the pressure of the operation would ease up and any leads would be lost.

"I reached the conclusion that we wouldn't be able to improve our intelligence, so we decided to take action," says Yariv.

"We realized we had one chance to get our hands on them. If we didn't catch them, the holidays would be here, and they could think we were on to them and cut themselves off again, and we'd need to start from the beginning," Yadai recounts.

The morning of Sept. 22, 2014, a few days before Rosh Hashanah, Yadai was at his son's brit milah. At the ceremony, he received an encoded phone call saying that there were signs that indicated an operation should take place that night.

"I finished up the brit quickly, went back to the army, and got the plan approved," Yadai says.

"That night, we approached four targets in central Hebron that the Shin Bet had identified," O. says. Counterterror police made up the innermost circle, surrounded by combat troops from the IDF's elite Duvdevan counterterror unit, which made sure that the area was clear of threats. Yariv sat in the command center and directed the operation. The details have never been made public.

"It was one of those moments you don't forget. There was a tense silence, fear, you could really feel it."

One of the targets that was surrounded was a carpentry workshop on the main street. At the same time, police counterterror personnel raided the home of the workshop owner and arrested him. A Shin Bet interrogator attached to the mission questioned him in the field. After a few minutes, he admitted that the terrorists were hiding in his workshop.

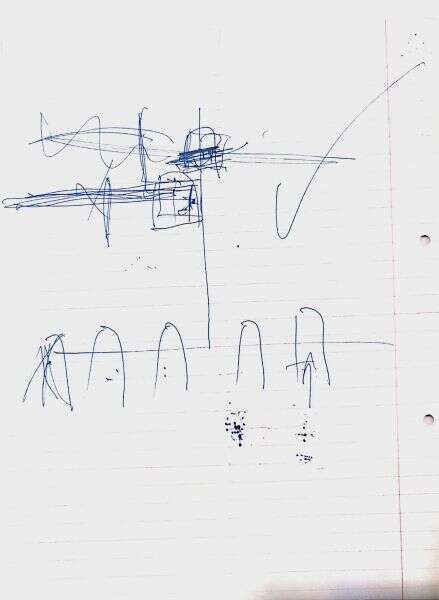

The Shin Bet interrogator took a piece of paper and a pen and asked the owner to sketch out where exactly they were hiding, so that forces could aim the operation at the right place. That drawing, which remains in the possession of the Shin Bet, is now published here for the first time.

The Palestinian drew a crude plan of the workshop. The bottom section of the drawing shows the doors that opened to the main street, and the top part shows the back façade of the workshop that could be entered by a side alley. It also showed a double wall where the terrorists were hiding.

"The entrance to the hiding place was behind a chest that was up against the wall. They had been hiding there for about two months, and the owner would bring them food and water. He would come to work in the morning, move the chest, they would go out, stretch, and eat, and go back in. And then they would go on planning the next terrorist attack," Yariv says.

Meanwhile, O.'s unit had begun working in the area surrounding the workshop. The soldiers moved civilians out of the way and called for the terrorists to come out. "No one answered. We know that's how terrorists behave at the start, in the hope that they can still escape. After a long while, I asked the command center for authorization to launch the operation," O. says.

The forces opened fire at the outer doors, but nothing happened. "We were really hoping for a response, even a volley of fire, because that would tell us they were there and the story was over," O. says.

At this point, O. was given the drawing of the workshop. He learned that the terrorists' hiding place was located below street level and that trying to reach them from the entrance to the workshop would be a problem.

"The drawing made the battle more comfortable for me, but not easier," he says. "It was a very complicated area for us because of the density of the home and the fact that it was located on the main street. We had to shut everything down to prevent the slightest chance that they'd escape."

"We fired a few shots at the workshop. We even fired a few anti-tank missiles, but there was no response," he says.

In the forward command center, which was located on the roof of a nearby building, Yadai was waiting. "At the start of the operation I expected we'd be able to get our hands on the terrorists right away, and when that didn't happen, I started to think that maybe they weren't there. That once again, we'd failed to find them."

A different tactic was needed, O. decided. Instead of trying to breach the walls, the forces would go in through the ceiling.

"I asked the commander of the second platoon, who had finished the operation, to arrest the workshop owner and join me. I placed him across from the place where I wanted to dig, and I got everyone ready for me to detonate an explosives load over the terrorists' heads, where we thought they were hiding, based on the sketch. I told them on the radio to place the explosives on the ceiling, between the two concrete walls, hoping that would end things."

A heavy-duty tractor was brought in to clear the area, and then the soldiers placed the explosives. The detonation went off as planned, but nothing happened.

"We started to have doubts. We said to ourselves, either we killed them, or they aren't there," O. says.

A few more minutes passed, and then the two terrorists popped out of the hole and began firing assault rifles. "I think that was the first time in my life that I was happy to be shot at," says Yadai. "I said to myself, tonight, it's over."

The counterterror police returned fire. One of the terrorists was killed and fell down, but the other one fell back inside the hole and it wasn't immediately clear whether or not he was still alive.

"The problem was that he'd gone back underground, to a place that was very difficult to reach from the start, and now a fire had broken out and there were flames and smoke, which made it very difficult for the forces," says O.

The forces were afraid that the second terrorist, who turned out to be Marwan Kawasme, would take advantage of the uproar to escape. While the soldiers were debating about what to do, he popped up out of the hole and began firing. One of the bullets struck the oil pipe of one of the pieces of engineering equipment that the soldiers were using, putting it out of commission.

"We managed to fire a few shots at him, and he fell back into the hole," says O. "But it was obvious he was alive, and we needed to continue."

Dawn was breaking and the commanders were worried that the city morning would bring riots and clashes. "We realized we needed to end the event. We decided to put a large number of explosives inside the workshop so the shockwaves [from the explosion] would do the work, bring down what was necessary, and not leave the terrorist any chance of getting out," O. says.

"We got the forces ready. And confirmed with the Duvdevan soldiers that the area was hermetically sealed, so we could operate in peace."

He asked his second in command to prepare a load of 4 kg. (9 pounds) of explosives, place them on a power shovel, and simply drop them into the hole that had been created in the first explosion. "It was an explosives load with a long lead time, but we shortened it so the terrorist couldn't throw it back out."

The explosives were placed inside the hole and a few seconds later detonated.

"All the walls of the workshop collapsed, and all the doors flew off. They were massive Arab doors, and I told myself that if they were blown off, there was no chance that human tissue could remain alive inside."

Yadai: "I look at the fire and the enormous damage and said, there's no chance anyone is coming out alive."

Palestinian firefighters were called in to put out the fire. Police counterterror troops and soldiers from the Duvdevan Unit stayed on-site to make sure the affair finally was over.

"The counterterror unit has a mantra we recite at incidents – 'There's no body until there's a body.' We want to see the body for ourselves because there have been cases where the terrorists came out alive and shot at us, or fled. So we needed to close the book," O. says.

It took an hour to extinguish the fire. Kawasme's blackened and burned body was found. His family and Abu Aysha's were summoned to identify them. When authorization was received, the affair was finally over. "It put a smile on our faces. We could celebrate the holidays happily," O. says.

Yadai: "The kidnapping incident is the kind of event we take with us to the grave, that carries with it a sense of guilt that it happened in your patch and on your watch. It's not that anyone will show up and accuse you of being responsible, but after you get to know the families, you feel even more of an obligation to bring the story to an end."

Yariv drove back to his office. "On the way, I called two people – [then] head of the Shin Bet Yoram Cohen, and our staff member who was responsible for contact with the families, so she could let them know that it was over."

"Ultimately, you're responsible for the territory and everything that happens in it, for good or for bad, it's your responsibility. And that responsibility goes with you 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, and there's nothing you can hide behind. That's the sense of responsibility that accompanied me both as a junior manager and now as a senior manager in the Shin Bet, and it was clear to me, after more than three years on the job that I wasn't leaving the obligation [to the families], or to whoever would succeed me. The day after wasn't a happy one for me, but I felt easier. I told myself that we'd gotten even."