The first thing to know about Israel's electoral system is that it has a serious flaw. The second is that it's very hard to fix it.

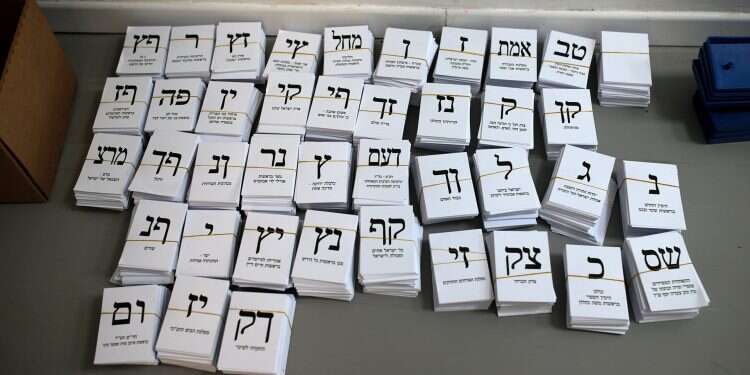

As you probably know, Israelis vote for parties, not for individual candidates. The parties pick ordered lists of candidates (how they do this is up to the parties), and each party gets a number of seats in the Knesset proportional to the number of votes it receives. The seats are ordered, so if a party gets a third of the total vote, the first 40 candidates on its list get seats.

Then the president will consult with the various parties and pick the Knesset member he believes most likely to successfully form a government. Usually – but not necessarily – this is the No. 1 member of the party with the most seats. Of course, no party ever gets a true majority, so after the election come the coalition negotiations.

In April's election, the constellation of right-wing parties, led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's Likud, came out far ahead of the Center-Left, led by Benny Gantz and his Blue and White party (actually, it's hard to call it a party – it's more like a conglomeration of personalities with differing political viewpoints who agree on one major principle: opposing Netanyahu).

Although the Likud by itself achieved only a small margin over Blue and White, Netanyahu's big advantage was that he had – or at least thought he had – enough coalition partners to put together a majority in the 120-member Knesset. Gantz was far behind, being unable to get 61 members in a coalition even if he were to ask the non-Zionist Arab parties to join him, something which hasn't happened in Israel's history.

Israeli coalition negotiations are notoriously ugly, with small parties trying to extort the maximum number of important Cabinet positions, promises to support or kill particular legislation, or money for pet projects or specific segments of the population, before they agree to sign on. But usually everyone wants to get on with it, and compromises are made before time runs out.

This time, one of Netanyahu's partners, Avigdor Lieberman, whose Yisrael Beytenu party is made up mostly of secular Russian immigrants, and which won five Knesset seats in April, refused to join the coalition unless the government passed a law Lieberman had initiated back when he was defense minister. The law calls for an increasing number of yeshiva students to be drafted and applies financial penalties to yeshivas that don't meet conscription targets.

The haredi parties would not agree, although they were willing to discuss a compromise. But Lieberman insisted: The law must be passed "without changing [so much as] a comma." Lieberman's five seats made the difference between a 65-seat majority and the inability to form a government.

Everyone believed that a last-minute compromise would be made, or that Netanyahu would persuade an opposition member to jump ship or pull some other rabbit out of his hat. But it didn't happen. Netanyahu's only options were to inform President Reuven Rivlin that he could not form a coalition, in which case Rivlin could ask Gantz or any other member of the Knesset to try, or to get the Knesset to pass a bill to dissolve itself and call for a new election. Whether anyone else could have succeeded was uncertain, but rather than take the chance, Netanyahu chose other election. They will be held in September.

Until then, Netanyahu will remain prime minister. The Knesset will not introduce any new bills. Soon the campaigns will start all over again. It's been estimated that the election will cost the Treasury 475 million shekels ($131 million), and the obligatory day off for all workers will cost the country as much as a billion shekels.

The lack of a government capable of making serious commitments will also mean that U.S. President Donald Trump's "deal of the century" – at least, the political part of it – will be put off until after the election, and after the coalition negotiations that must follow. That won't be until the end of the year, which will be just about when the pre-election frenzy in the United States starts. Various domestic issues of importance will languish, such as the reform of Israel's Supreme Court, which I believe is essential and should be decoupled from any attempt to grant Netanyahu immunity from prosecution on the several corruption charges pending against him.

And it's possible that the whole thing could happen again this September.

It's totally unacceptable that the creation of a new government can be stymied by one stubborn individual, whose party received about 4.2% of the vote.

The general problem is the way a small party can exploit its position to gain massive leverage and benefits. The haredi parties, who are prepared to go with either the Right or Left depending on who offers them the best deal in cabinet positions, money for yeshivas, freedom from military service, and Torah-based legislation, are famous for this, but they are not the only ones that do it. Of course, this applies once there is a government as well as at coalition-making time; if they are unhappy, they can vote with the opposition to bring down a government.

The bribes paid to the various prospective coalition partners – and bribes are exactly what they are – are expensive. New ministries and their staffs are created to give jobs to important partners. Institutions are subsidized, welfare benefits for particular segments of society are expanded, and so forth. The negotiators are generous. Why shouldn't they be? It's absolutely vital (they think) that their party get to lead the nation, and it's taxpayer money anyway.

There were too many small parties, so the percentage of the vote needed to get into the Knesset was raised. It presently stands at 3.25%, which means that if a party doesn't get that many votes (equivalent to four seats), they get no seats and their votes are lost. This is what happened to my vote this April when the New Right party of Naftali Bennett and Ayelet Shaked missed the cut-off by a mere thousand votes. Now there aren't numerous one- and two-seat factions in the Knesset, but the extortion problem still exists. And the high cut-off harms the medium-size parties because it impels voters to choose the biggest parties out of fear of having their votes neutralized.

There are some very good things about Israel's system. A citizen makes a clear ideological choice in voting for a party, and Israelis care about ideology. Even if you vote for a party that just makes it over the threshold with four or five seats, your people will have influence in the Knesset, and perhaps in the cabinet, if they join the coalition. Unlike the American or British systems in which parliamentary candidates stand for election from geographical districts, there is no problem of gerrymandering (drawing district boundaries to disenfranchise voters of a particular party or particular ethnic groups). The gridlock caused by a conflict between the executive and legislative branches, so characteristic of the American government, is far less likely.

I don't have an easy solution. Politics is politics, and it will always involve deals in smoke-filled rooms. But is there anything we can do to clean up the coalition system without losing the worthwhile parts?

This column first appeared on AbuYehuda.com and is reprinted with permission from JNS.org.