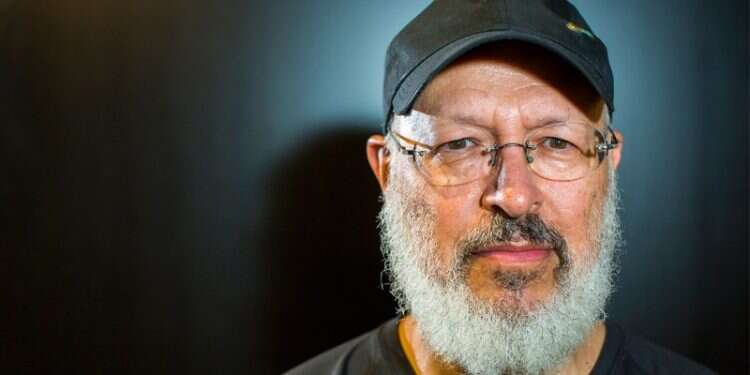

Artist and graphic designer Yossi Lemel, the son of Holocaust survivors, often asks himself to what extent the Holocaust can be studied on a personal level, and the personal applied to the collective.

"Until age 30, I barely dealt with the Holocaust. Dad talked very little about what he went through. He arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau with his father, and he was chosen for Dr. Josef Mengele's experiments. Eleven young people from his home community of Bedzin were chosen. The one who actually conducted the experiments was Mengele's assistant. [Dad] went through hell and couldn't talk about it for years," Lemel tells Israel Hayom.

"Today, I know that they experimented on them by injecting them with hepatitis B. On some, they performed liver biopsies without anesthetic. He went through the experiments at the Auschwitz I camps. He was also an errand boy who carried messages to Mengele. He said that every time he saw Mengele he'd run away. The man was a monster. Dad also witnessed experiments they did on others. Today, he's 92 and for years he kept silent about the hell he endured there. My mother also experienced the Holocaust in the town of Bedzin, as a member of the Radomsk hassidic community. She was actually the one who talked about it."

When Lemel decided to touch this open wound, he started traveling to Poland. On one trip, he retraced his father's footsteps. On another, his mother's, and on a third trip, his maternal grandfather's, who moved from place to place, following the Radomsker rebbe. On each trip, he created work for large-scale graphic exhibits that focused on the private destruction his family experienced as a way of making the disaster that befell the Jewish people palpable to viewers.

"I don't create these pieces to earn money, but rather to be a tool of memory. The way I see it, I'm a conduit through which the memory of the Holocaust is passed on to future generations. I don't sell the work and I don't make money off it," Lemel says.

Lemel, 61, studied graphic design at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. He is mainly known for his political posters, many of which deal with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He says that the first trip he photographed and edited into an art piece followed his father's childhood, starting in Bedzin in southern Poland until the time he reached the Auschwitz death camp.

"I was photographed in place of him. I photographed myself shaved and dressed in a prisoner's uniform in the Auschwitz blocks, when the temperature was -23° C [-9° F], and in the forest, too. While I was taking pictures, I was talking to my dad on the phone. The experience was amazing in its awfulness."

In the exhibit dedicated to his grandfather and his family, Lemel photographed the synagogue where his grandfather used to pray, with his own image reproduced over and over again in different positions. This is how Lemel portrays the people who are no longer alive and left gaping holes behind them.

"There are almost no Jews in Poland anymore, just crumbs. So I created a piece in which I take a picture of myself in a synagogue, reproduced until [the synagogue is] full of my own image. I also made a big piece featuring the tattooed number given to my father at the death camp," Lemel says.

This unusual piece of work was displayed on an entire floor of the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Hamburg, Germany, and sparked great interest among German visitors.

"A catalog of the show, which included a giant poster of my father's concentration camp number – six digits on [a poster] 6 meters [20 feet] long – was signed by Germany's foreign minister at the time, Joschka Fischer. I took the signed catalog to my father, who told me, 'Leave it. I already have the Germans' signature on my left arm. I don't need another one.'"

Lemel has also enlisted his family for his pieces. He photographed his younger daughter six times, for the six sisters of his mother, Batia Garfinkel-Lemel.

"Mom came from the Radomsk Hassidim, the biggest hassidic sect in southern Poland. They had 50,000 Hassidim and more than 36 yeshivas. The rebbe moved to Bedzin, and my mom and her family followed him. Later, my parents married," he says.

Lemel's parents survived the Holocaust, but the Radomsker rebbe (Rabbi Shlomo Hanoch Hacohen Rabinowitz), who chose to remain with his Hassidic followers, was subjected to brutal torture and secretly moved to Warsaw, where he was shot to death in 1942. Some of Rabinowitz's relatives were killed along with him, and other than a few survivors his Hassidic sect was wiped out. The murder of an entire branch of Hassidic Jewry prompted Lemel to take a third trip to Poland, where he created a piece portraying the various stages of the rebbe's life.

Lemel says that the trip was important to him on both a personal and a national level.

"I wanted to heal the tear and restore to our people an entire part of it that was lost, which we don't deal with at all because of the national trauma we went through. Wherever I give my lecture in Israel, people who are as far as they could be from the world of hassidism suddenly start talking about their [personal] links to the Holocaust. I don't mean religious links, but the link itself, the understanding that we are part of an entire people. I'm not talking about a connection to religion, but rather a connection to the Jewish identity that came apart, that was rent asunder, in the Holocaust.

"In the early days of the state [of Israel], no one talked about the Holocaust. The Eichmann trial opened the gates, but as an artists I feel that we haven't worked through the tragedy. My mission is to introduce the public to their ancestors," Lemel says.

Lemel's father's fragments of stories influenced him deeply. He used them as material in his other work, including some about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. "My work expresses the fears and threat that I absorbed unconsciously," he says.

Q: How to Israelis respond to your presentations?

"One totally secular woman told me, 'You know, I'm the great-granddaughter of the Chazon Ish [Rabbi Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz.]' And she's not alone. There is a real thirst not only to deal with the Holocaust, but also to remember the Jewish world for the past 2,000 years. I create graphic, political presentations. I've done posters for Amnesty International, for Greenpeace. I've had shows all over the world. I see my work as a mission.

"For example, everything about Greenpeace is important to me as an artist. The planet is a gift, and we need to preserve its sustainability. As someone who grew up in a home with a religious mother and a secular father who is angry at the Creator, my art is a way of connecting to the sacred. All creation is sacred. The planet is sacred and unfortunately, we are desecrating it.

"I have a lot of work about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, about the world, about refugees, but here, I see my main work as bringing the fading coals of our connection to our people to life. In Poland and Germany, people flock to my shows en masse.

"Masses of Poles came to my exhibit about my mother, which opened at Poland's National Museum in Poznan in the summer of 2008. Here, in Israel, the wound is still painful. We tiptoe around the subject. It's not easy for me, either, but I think that this is a way to understand where we came from."

Lemel creates his pieces in his free time. He spends most of his days running the ad agency Lemel Cohen, and lecturing at the Holon Institute of Technology.

Q: An ad man focuses on short, catchy messages, while art has a dimension of depth and delay. How do you bridge these two fields?

"In advertising, you need to send a message using a short design, with a short name - build a brand. A lot of thought and artistic work goes into advertising, too. But obviously, art has a deeper layer. I see my presentations about the Holocaust as my [artistic] peak. That is what I was put here to do, to be a conduit for that memory.