When Jacek Czaputowicz was appointed foreign minister of Poland this January, he never imagined the diplomatic brouhaha in which he would soon be embroiled. His main mission was to improve relations between Poland's conservative government and the European Union. But since then, populist elements in the Polish governing coalition prompted the government to adopt an amendment to a law which makes it illegal to blame Poland or the Polish people for Nazi atrocities committed in occupied Poland during World War II. The vote was held on the eve of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, and sparked a crisis, and not only because of the timing.

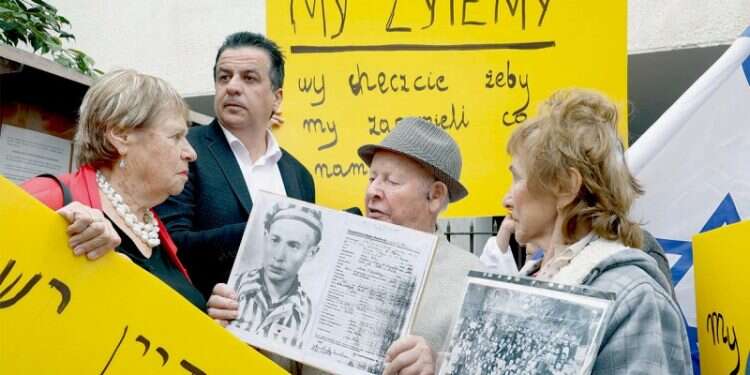

The amendment rocked Poland's relations with Israel and the Jewish world at large. The crisis caused old tensions and grudges to float to the surface, posing the threat to the delicate ties that have existed between the three sides in the past few decades.

Attempts to find a solution to the crisis that would not cause the Poles to feel that they had been forced to cave to outside pressure or portray the Israeli government as a partner in "rewriting" the history of the Holocaust went on for five months. The joint declaration by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki on June 27 might have been the target of criticism from Yad Vashem, but also paved the way to rebuild trust between Warsaw and Jerusalem.

Czaputowicz was supposed to have visited Israel this week – the first visit by a member of the Polish government since the crisis erupted - but Netanyahu requested that the visit be postponed because of heightened security tensions. Czaputowicz and Netanyahu are scheduled to meet a few weeks from now on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly in New York.

In an interview to the Israel Hayom weekend magazine, Czaputowicz parses the crisis over the Holocaust law and its ramifications.

"In Poland, we don't call the amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance the 'Holocaust law,' but rather the 'anti-defamation law,'" Czaputowicz begins.

The foreign minister explains that critics of the act were worried that the amendment would restrict the freedom to research and discover the truth about the Holocaust, "that it would make Holocaust survivors fear that they might, for example, be imprisoned for portraying Poland and Poles during that time in a negative light in their memoirs," he tells Israel Hayom.

"Another line of criticism was that the act would limit freedom of speech and expression. However, it was about preserving the truth about the Holocaust, not about distorting knowledge about the Holocaust," Czaputowicz emphasizes.

Czaputowicz says that the discourse of the past few months has been "painful" for the Poles who were accused of wanting to misrepresent historical truth, whereas, he says, they actually sought to defend it.

"We have witnessed an increase in the number of public statements that distort the truth about the Holocaust by deliberately attributing German crimes against Jews to the Polish state and the Polish nation," he says, adding that Poland's diplomatic missions are "struggling to keep up" with the number of corrections they need to issue – for example, asserting that the death camps that operated in Poland during the war were "German Nazi extermination camps" rather than "Polish death camps."

In Israel, too, Czaputowicz says, the term "Polish death camps" was used, at times out of "spite."

"I think there has been some resentment, but I hope it won't be an obstacle to [Polish-Israeli] relations. … We want to maintain contacts at all levels, including economic and cultural relations, between our societies," he says.

Czaputowicz points out that Poland's parliament, the Sejm, has removed articles from the law that allow for legal sanctions for the deliberate, inaccurate attribution of German Nazi crimes to the Polish state or Polish nation as a whole.

"Our position is that it is better if we can ensure the protection of historical truth without resorting to criminal sanctions. The declaration by prime ministers Netanyahu and Morawiecki gives us grounds for hope," he says.

Q: Did you expect such harsh reactions from Israel?

"The extent of the reaction was a surprise, especially given that 12 years earlier similar provisions were introduced into Polish legal statute, and Israel said nothing."

Q: What is your analysis of the crisis? Was it the result of a series of mistakes that started on a very symbolic day and was ignited by populist politicians on both sides, or was it an existing wound that was poised to re-open?

"It was a complete accident that the Sejm adopted the [amendment to] the law on that symbolic day. I would compare it to a forest fire: the immediate cause was a spark – the Sejm's adoption of the amendment and Israeli Ambassador to Poland Anna Azari's speech at Auschwitz in memory of the victims of the Holocaust.

"But the [underlying] causes of the fire were at the government level – the populist policies of opposition circles in Poland and the dispute in Israel.

"In Poland, comments by some Israeli politicians in the international press have been seen as attempts to check our sovereignty. It turned out that underneath the apparently good relations between Poland and Israel, there were deep resentments and emotions that have [now] come to light. Some opinions expressed in Israel were a shock to many Poles.

"The differences are difficult to overcome because they have to do with national identity – who we consider ourselves to be, and how we want others to see us. Under communism, we were far apart, a fact that contributed to the creation of separate narratives about our shared history," Czaputowicz says.

The foreign minister adds that Israel and Poland have much work ahead of them to reach mutual understanding.

Q: As the crisis escalated, some of the reactions showed that anti-Semitism is still very much present in some sectors of Polish society. The Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs published a troubling study that exposes the extent of renewed anti-Semitic discourse in Poland in the wake of the controversial "Holocaust law."

"There were indeed statements in Poland that could be classified as anti-Semitic. Many people tried to make our case, not always choosing the right arguments, or by employing stereotypes. However, I don't place much academic value on the article to which you refer.

"The author quotes the statements from some (rather second-rate) Polish journalists and politicians. They were made, but he does not put them in context. I think it would be easy to write an equally critical article on anti-Polish attitudes in Israeli society, quoting and comparing selected statements by journalists and politicians, and adding a picture of a Polish embassy covered with swastikas. Can such articles be called serious academic studies?

Czaputowicz points out one sentence he says escapes the reader: "Andrzej Duda, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, and leader of the Law and Justice Party Jaroslaw Kaczynaki issued statements condemning anti-Semitism in more general terms."

Why, he asks, does the author not develop the idea that the Polish government and authorities condemn anti-Semitism?

"In July, I attended a conference in Washington dedicated to religious freedom. During this meeting, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence spoke about anti-Semitism as a threat to religious freedom, giving the examples of Great Britain, France and Germany. In these countries, Jewish religious leaders have recommended that Jews not wear articles that identify them as Jews – such as kippahs – lest it put them at risk. When criticizing Poland, things need to be kept in proportion. In our country, Jews can feel safe, practice their religion freely, and develop their culture."

Q: What is your answer to Yad Vashem's criticism of the joint statement issued to resolve the crisis?

"In my opinion, it reflects the essence of our relations during the Holocaust well. I think that from a historical perspective, it will be highly valued by both countries. The prime ministers were able to rise above a current political dispute and adopt a document that paves the way for cooperation, including when it comes to investigating the difficult chapters of our history.

"Three historians affiliated with Yad Vashem presented their own assessment of the statement. In my opinion, they over-interpreted some of the declarations. In Poland, there is no threat to the freedom to research the Holocaust. Recently, many critical works have been published that are the subject of intense debate. It's natural for researchers to differ in their assessments of historical events.

"Were the cases of Poles rescuing Jews rare, while denunciation or the murder of fugitives from the ghettos numerous? That's difficult to resolve. The prime ministers' declaration doesn't attempt to resolve this; it acknowledges that both these cases existed.

"During the Holocaust, Poland did not exist as a country on the map of Europe. Hiding Jews was punishable by death. The so-called 'navy blue' police were part of the occupier's [Germany's] apparatus, and although it was mostly made up of Poles, calling it 'Polish' is misleading.

"It is also difficult to accept the attempt to exclude institutions whose aim was to help Jews. … The article is worthy of serious debate, which is the right way to reach historical truth, but this can be done more effectively when the dispute has cooled down."

Czaputowicz also points out that when the crisis over the Holocaust law was at its apex, German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel spoke up and stated that the full blame for the Holocaust lies with the Germans.

"There is no doubt as to who was responsible for the concentration camps. This organized mass murder was committed by our nation and by no one else. If there were individual collaborators, they do not change anything here," Gabriel said, adding that it was "no coincidence" that the Germans located their death camps in Poland, hoping to destroy both Polish culture and exterminate the Jewish people.

Q: What lessons have you drawn from what happened between Poland, Israel and the Jewish world in the past six months?

"I'm trying to find some positive aspects to this dispute. The intentions of the Polish side were pure. It wasn't about distorting the history of the Holocaust era, but about preserving the truth about it. When we realized that both sides were basically trying to do the same thing, we were able to compromise. The changes introduced by the Polish parliament should be interpreted as a willingness to search for the truth about the Holocaust together."

Q: What is your personal connection to the war?

"I was born in Warsaw after the war. My paternal grandfather was an officer in the Polish Army. He took part in the September 1939 campaign and was taken prisoner, spending more than five years in a German camp. The husband of my grandmother's sister died in Katyn, murdered by the Soviets, and two of her sons were killed in the Warsaw Uprising. My in-laws were officers in the Home Army, they fought in the Warsaw Uprising, and during the Stalinist period they spent many years in a communist prison, and in exile in the depths of Russia. The war affected many Polish families, especially those in Warsaw.

"At this year's events commemorating the 75th anniversary of the outbreak of the Ghetto Uprising, President of the World Jewish Congress Ronald Lauder recalled that a year after a group of Poles of Jewish descent rose up against the Germans, the entire Polish underground started a struggle against the German occupier. The people of Warsaw, Jews and Catholics, demonstrated courage in fighting German Nazis.

"For me personally, the history of Polish Jews is part of the history of Poland. During my youth, I was interested in their fate. I often visited abandoned Jewish cemeteries. Later, while active in the opposition in the late 1970s, we condemned the anti-Semitic campaign the communists unleashed in 1968. In the opposition, I cooperated with many colleagues of Jewish descent. We opposed the injustice of communism, and it didn't matter whether someone was a Jew or not."

Q: Are you planning to Israel soon?

"I certainly would like to visit Israel and we are looking for a time that would be convenient for both sides. I would be also glad to visit Yad Vashem, as it is a very important institution involved in the study of the Holocaust. We would like to resume the educational agreement on cooperation between Yad Vashem and [Poland's] Institute of National Remembrance."

Q: Will Poland join the renewed U.S. sanctions against Iran?

"It's not good for Poland when the policies of the United States and the European Union diverge. It's in our interest to strengthen transatlantic relations. Our position in the EU forum is that we fully understand the American policy toward Iran. However, our membership in the European Union makes it impossible to conduct independent policy regarding economic sanctions."

Q: How does Poland view the Trump-Putin summit?

"I visited Washington after President Trump and President Putin met in Helsinki. Representatives of the American administration assured me that there is no fundamental change in U.S. policy toward Moscow. We also see a chance for the Helsinki meeting to yield positive results in restoring calm to Syria, which is important for the security of Israel.

Q: Will Poland be willing to move its embassy to Jerusalem?

"Poland has an honorary consul in Jerusalem, Mr. Zeev Baran, who performs his function well. We will coordinate our position on any possible move of our embassy to Jerusalem within the framework of the European Union. I think that finding a sustainable solution to the crisis in the Middle East would help the international community decide on that issue."