The string of successful Israeli intelligence efforts against Iran in recent years, aimed at undercutting the Islamic republic's nuclear program and thwarting its attempts to entrench itself militarily in Syria, have created the public perception that this campaign comprises only one side, which does what it will in this arena.

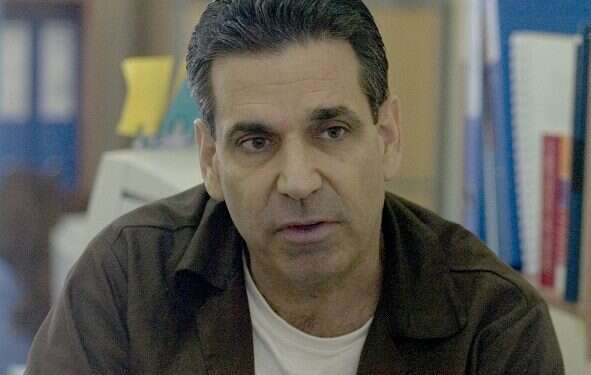

The Shin Bet security agency's announcement that it arrested disgraced former Energy Minister Gonen Segev on allegations of espionage for Israel's archfoe Iran, proved otherwise. Segev may have volunteered to serve the Iranians, but his actions allowed for a glimpse into the efforts made by the other side, namely Iran's effort to spy on Israel, infiltrate its territory, recruit agents, and plan operations that would allow it to both launch attacks or exact revenge.

Segev's handlers were officers with the Ministry of Intelligence of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the country's primary intelligence agency alongside the Revolutionary Guards' intelligence apparatus. The agency, known as MOI, allegedly reports to the Iranian Prime Minister's Office, but in reality, it enjoys full independence and answers only to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The MOI was established in during the era of the Shah, when Israel and Iran enjoyed close ties, and like most other security organizations in Iran, it was established based on Israeli knowledge and under the guidance of Israeli defense officials. It is not surprising that the MOI is similar in structure to the Mossad, Israel's national intelligence agency, or that it employs similar doctrine and practices.

"Add to that the Iranians' inherent dedication, intelligence and learning abilities and you get a serious opponent who should not be underestimated," a former senior intelligence official told Israel Hayom.

Iranian intelligence gathering efforts focus on a long list of targets, but its three primary interests include its immediate vicinity, namely the Persian Gulf, where it places an emphasis on Saudi Arabia, the Sunni world and the oil interests that drive its economy; Israel, as a staple Middle East entity, alongside Tehran's interests in Lebanon and Syria; and the United States, particularly U.S. activities in the Gulf.

Much like the Mossad and other intelligence agencies around the world, the MOI employs a wide variety of capabilities, including counterintelligence and maintaining ties with other spy agencies, including in countries friendly to Israel that maintain extensive ties with Iran.

Naturally, the agency's main operations focus on intelligence gathering, which stretches all familiar avenues and includes human, signals, imagery and cyber intelligence. These efforts are global: Every Iranian embassy has an MOI officer – sometimes more than one – among its personnel and they answer directly to Tehran.

Over the years, Iran has made quite a few attempts to recruit Israelis. The methods were varied: At first, efforts were focused on Jews who immigrated to Israel from Iran. Iranian intelligence tried to blackmail some into cooperating by putting pressure on relatives who remained in Iran; others were offered money, and in some cases, the MOI tried to appeal to the expat's longing for their homeland. These are all excellent recruitment methods used by every intelligence agency in the world, and the Ministry of Intelligence is no different.

In the 1990s, Iran attempted to turn Jews who immigrated to Israel during the wave of immigration from the former Soviet Union. In the years to come, the focus shifted to Arab Israelis, whose handlers were based both in Tehran and Lebanon.

Qais Obeid, an Arab Israeli from Taybeh who once worked for the Shin Bet and Palestinian intelligence, was recruited by Hezbollah, Iran's proxy in Lebanon, in the late 1990s and started running agents in the Middle East. Segev was one of his top marks and was lured to do business with Gulf states, completely oblivious to a plot to abduct him.

As Segev and Obeid's relationship grew closer, the Shin Bet was alerted to it and was able to warn Segev of Obeid's nefarious intentions. The latter then turned his attention to another potential asset and facilitated the abduction of Col. (res.) Elhanan Tannenbaum in 2000. Tannenbaum, whose capture seriously compromised national security, was released in January 2004 as part of a controversial prisoner exchange deal with Hezbollah.

Hezbollah may have executed Tannenbaum's abduction, but it was clear that Iran was behind the operation. It was Iranian infrastructure that allowed for him to enter Dubai, where he was eventually snatched, and it was Iran that supplied the Hezbollah abductors with safe houses and the plane on which the Israeli officer was transported to Lebanon. Iranian intelligence officers had also interrogated Tannenbaum while in Hezbollah captivity, and there is no doubt they benefited from the information he provided.

"It was an Iranian operation carried out by Hezbollah, just like many other attacks we have seen overseas," a senior Israeli official said.

While the similarity to overseas attacks exists, those are usually the handiwork of the Revolutionary Guards' intelligence apparatus and the Quds Force, the IRGC's black-ops arm. The MOI and the Revolutionary Guards both answer directly to the supreme leader, but they rarely collaborate.

Like the American Central Intelligence Agency, IRGC intelligence is autonomous and self-contained, from recruiting and handling agents, through a secret unit in the Iranian Foreign Ministry that ensures they have overseas access and infrastructure, to various intelligence gathering avenues, such as wiretapping, regular and cyber surveillance and drones.

As demonstrated in February during the Iranian drone incursion into Israeli airspace, Lebanon and Syria's shared borders with Israel allows the Quds Force to gather intelligence in a variety of methods, from observations points to using local shepherds to gather tactical information along the security fence.

Shady business

Iran's operational intelligence infrastructure facilitated quite a few terrorist attacks against Israeli targets around the world in the past, most prominently the 1994 bombing of the Argentine Israelite Mutual Association in which 85 people were killed and hundreds were wounded. Although Argentina did its best to cover up the evidence, there is solid information indicating Iran was involved in the attack, believed to be retaliation over the assassination of then-Hezbollah leader Abbas al-Musawi by Israel.

The 2008 assassination of Hezbollah's iconic military commander Imad Mughniyeh in Damascus, which foreign media attributed to Israel, launched a global Iranian reprisal effort that included targeting several Israeli assets around the world and Israeli efforts to counter Tehran's plans.

At the time, the intelligence race between Iran and Israel encompassed the world and included quite a few successes on Israel's part in thwarting attacks in the Far East and in Europe. In two cases, the attacks were successful – the 2012 attack against the wife of a Defense Ministry emissary in New Delhi, and the 2012 Burgas bus bombing, which targeted Israeli tourists.

While Hezbollah had carried out the attacks, Iran gave the orders, supplied the intelligence, created the operational infrastructure and had operatives on the ground – operations officers who arrived in both locations just before the attacks took place and disappeared without trace promptly afterward.

Orchestrating these attacks undoubtedly included meticulous intelligence gathering.

"The Iranians are obsessed with gathering intelligence worldwide," a defense official said this week. "They have operational infrastructure across five continents, with ready-made terrorist attacks they can execute once an order is given. Their people are constantly updating the information about their opponents, including us."

It is also likely that this was part of how the Iranians handled Segev, learning about the Israeli Embassy in Nigeria, the Israeli emissaries and businesspeople who live there or visit often, etc.

His interrogation shows that he tried to set the Iranians up with various individuals under the guise of business meetings. This is a familiar pattern of action for all intelligence agencies and the MOI is no different.

Over the years, Segev and his Iranian handlers reportedly tried to contact Israeli businessmen in various ways, including officials in the defense industries, while others were placed under surveillance. One Israeli academic was even approached about attending a professional conference in Tehran.

This activity sought to establish intelligence infrastructure. It is unlikely Segev had any meaning full information to share, and the little he did was relevant to the 1990s. It is also highly likely that the Iranians were suspicious of the former Israeli minister-turned convicted drug smuggler who left Israel for Africa, and they probably cross-referenced the information he provided diligently.

Still, the Iranians kept Segev on their payroll. This probably stemmed from a number of reasons, some relating to Segev's character – he is a charming conman – and some relating to the opportunities he created, from his potential abduction to the connections he tried to cement between his handlers and various former senior officials.

The Iranians' attempt to lure Israeli officials under the guise of business opportunities with foreign counterparts is essentially an endless area of activity. There are quite a few Israeli businesspeople who travel around Africa in search of big money, which has grown even bigger in the cyber age. Some of them have a checkered past and more than a few have been known to walk – and at times cross – the fine line between legal and illegal ventures.

In business meetings, they try to impress their listeners with details of their knowledge, connections, goods they can provide, etc., something a skilled handler can milk further. All he would need is the e-mail address of one contact to create a basis for an intelligence operation that gives the Iranians access to numerous individuals and computers in Israel. Segev was a prime mark for all of this.

His arrest – an Israel Police-assisted Shin Bet operation based on actionable Mossad intelligence – was an achievement marred by a sense of failure. Segev was a lone wolf operating under the radar in a distant country, who was active for years before he was caught.

"The fact that Segev betrayed the country and became a spy was shocking, but it's hard to say that anyone in Israel was surprised by the fact that Iran was acting here and managed to recruit an agent," a former senior official told Israel Hayom. "If anything, the fact that there are spies in Israel should be the working assumption. Gonen Segev is not the only one."

Not all about the money

This premise led the Shin Bet to expand its counterintelligence division. The unit focuses on both Israeli and foreign assets, as it is clear to the local intelligence community that, alongside the entities trying to gather intelligence in Israel for security or commercial reasons, the Iranians are major players here.

Some of Iran's intelligence-gathering efforts are overt and are based on the fact that Israel is a democracy in which the majority of information is disseminated by the media, but some are rooted in classic spycraft, primarily the use of agents. There have been many cases which it was revealed that Iranian agents approached Arab Israelis and Palestinians who reside in the West Bank. It is also likely that many of them became double agents, who spy on Iran.

In this respect, Israel has a significant advantage over Iran.

"We are better from operational, intelligence and technological standpoints, both defensive and offensive, part of which is recruiting agents," a top official explained.

"It's rare to find an Israeli willing to betray his country. If anyone here wants to leave the country, they get on a plane and leave. The situation in Iran is different – the economy is unstable and people are desperate. It certainly creates more opportunities, but make no mistake – recruiting agents is very difficult, for us too. You could spend years on a potential asset only to fail," he said.

Those who know Segev are convinced he was not motivated by money. He was greedy, that much is obvious, but he was trying to exact revenge on a state that he, in his twisted logic, believed had abandoned him. He also sought to restore his sense of importance and to feel wanted and vital. In this respect, Segev is not alone. It is likely that others like him are walking among us, and it is equally likely that various intelligence agencies are trying to get their hands on them.

"The working assumption in intelligence is that you only know what you know and you should question what you know," another official said. "This would be the wise course of action when it comes to Iran and its counterintelligence efforts against Israel, as well as with respect to its intentions in Syria and its nuclear program.

"If there is anything we learned this week – again – is that Iran is a serious, determined, studious and patient enemy, and that we should treat it as such if we want to guarantee that we always remain at least one step ahead," he said.