1.

Purim came and went, and we have all taken off our costumes. In many cultures, dressing up is perceived as a transformation. Once we don a costume, we are no longer who we were, even after we remove the mask. We are actually reborn, having integrated into another form, like a butterfly emerging from a cocoon.

In many instances, people need costumes to attain freedom. In honor of this time, between Purim and Passover, I would like to offer a Purim gift to our readers after so many weeks of exhausting political stories.

The Book of Esther, which we read every Purim, is the great book of secularization. God does not appear in it at all. It is like a newspaper feature: It sticks to the facts, describing only what happened. Queen Vashti just happened to be banished from the palace; Esther just happened to arrive at the palace just as the bitter enemy of the Jews was about to achieve great power and her uncle, Mordechai, just happened to thwart a planned putsch. Of all the books in the Bible, secular Jews can read the Book of Esther without fear of religious "indoctrination."

2.

But our sages decided to include the Book of Esther in the Bible at a certain point in time, making it a part of the religious canon. By doing so, they were offering a different take on history. The fundamental book of the Bible – Genesis – already teaches us to interpret history on two planes. Things happen on the surface (for example: Joseph dreams and his brothers, fearing his growing power and his preferred status with their father, decide to get rid of him), but in reality, their deed (which, to them, appeared to be a tragic end to the story) actually made Joseph's dream come true.

And it is not just young Joseph who dreams. There is an even deeper dream – dreamed by the father of our nation, Abraham, in the story of the covenant of the pieces. "Know of a surety that thy seed shall be a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them; and they shall afflict them four hundred years; and also that nation, whom they shall serve, will I judge; and afterward shall they come out with great substance. … And in the fourth generation, they shall come back hither." (Genesis 15:13–16). Before the Israelites can transform from Abraham's family into a great nation, they must integrate into another nation, don the costume of Egyptians and melt into the national womb of another ancient empire. Only after that, the slaves can remove their costume and realize that what they thought was their identity was merely a mask that they must take off. It is at that moment of realization that their rebirth begins, culminating with their exodus to freedom in the land of their forefathers.

Unlike the Book of Esther, in Genesis, the dual interpretation is overt. Joseph tells his brothers: "So now it was not you that sent me hither, but God; and He hath made me a father to Pharaoh, and lord of all his house, and ruler over all the land of Egypt" (Genesis 45:8) and later, "And as for you, ye meant evil against me; but God meant it for good, to bring to pass, as it is this day, to save much people alive" (Genesis 50:20). In other words, what you see isn't always what is actually happening behind the scenes.

3.

The Book of Esther came at a historical time when our nation was facing exile and destruction, without any divine guidance and refusing to acknowledge the inner current that was pushing the nation along through trials and tribulations. A drunken king was matched with a bitter enemy to offer a final solution to the Jewish issue.

Our sages, who faced similar hardships under the rule of the Roman Empire, having lived through days of blood and violence, offering a faith-based interpretation of the story of Esther from the point of view of a nation that had seen it all and survived. In their interpretation, Esther is the alef (the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet and the first letter of the words Esther and God) in the "seter" or hiding. In other words, God is hiding behind global events and leading our people through the valley of the shadow of death through destruction and redemption.

In the beginning of the 20th century, Jewish thinkers used to spell the Hebrew word for history with a tav (the last letter of the Hebrew alphabet) rather than a tet, making it a derivative of the same "seter" – an amalgamation of "hester" with the suffix "ya" – a common moniker for God. In this interpretation, history means an incognito God.

Much like the countless government corruption allegations that we are bombarded with in recent months, the debate does not end with the facts, but rather with the interpretation of the facts. Our sages offered a decoder key to anyone interpreting the Book of Esther: Anywhere the book says "hamelech" (the king) with the "ha" (the) prefix, God is hiding there.

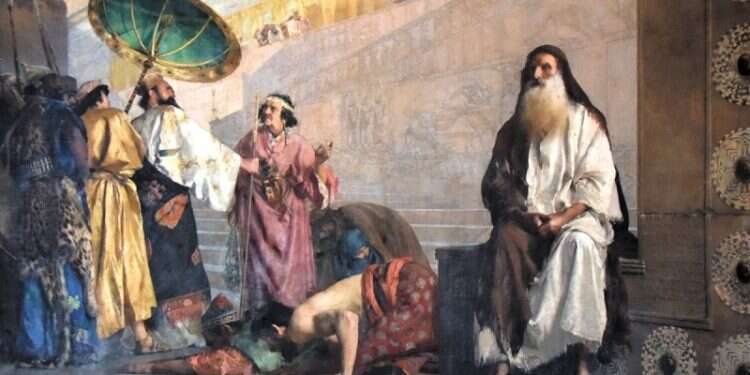

The Jews were in a delicate political predicament. An evil man had risen to power in the empire – someone you don't want to mess with. And indeed, "And all the king's servants, that were in the king's gate, bowed down, and prostrated themselves before Haman; for the king had so commanded concerning him" (Esther 3:2). The king's servants are the closest to the king – the leading socio-economic elite. If the king ordered it, they will bow before him. That's what's important. But our sages suggest that the servants are the servants of God, making them the religious scholarly elite of the Jewish people.

But at the end of the same verse, the opposite emerges: "But Mordechai bowed not down, nor prostrated himself before him" (Esther 3:2). And the horrified elite responded: "Then the king's servants, that were in the king's gate, said unto Mordechai: 'Why transgressest thou the king's commandment?'" (Esther 3:3). This could jeopardize not only the Jews' relations with the monarchy (at that point no one imagined that the result would be a declaration of total war against the Jews), but it is also a violation of the will of the king of the world, who selected his man to head the empire. Bow down to him. We mustn't rebel against the nations.

But Mordechai insists. He was a wise man, after all. And still, or perhaps because he was so wise, he preferred to risk his people. What did he see that his contemporaries didn't?

4.

This dispute reflects the two schools of thought that have existed among us since our inception as a people. Some 700 years later, when the Romans imposed their decrees on the land of Israel in the second century, a similar dispute erupted, as recounted in the Talmud:

When Rabbi Yossi ben Kisma fell ill, Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion visited him. Yossi advised Haninah to exercise extreme caution, if not submission. He said "Haninah, my brother, seest though not that this Roman people is upheld by God himself? It has destroyed his house and burned his Temple, slaughtered his faithful and exterminated his nobles; yet it prospers! In spite of all this, I hear, thou occupies thyself with the Torah, even calling assemblies and holding the scroll of the law before three."

With this, Yossi extended to Haninah the same criticism that the "king's servants" leveled at Mordechai: If you are a devout man, accept the rule of the Romans, because clearly, God chose them to rule over you.

To this, Haninah replied: "Heaven will have mercy on us."

Yossi became impatient on hearing this, and rejoined, "I am talking logic, and to all my arguments thou answerest, 'Heaven will have mercy on us!' I should not be surprised if they burned thee together with the scroll."

So what did Haninah actually say? Perhaps he meant that, in his view, one mustn't just accept things, such as the Roman rule over the land of Israel, as they are. Undesirable situations should be taken as a challenge, and by resisting them one can create the desired historical dialectic. The political and cultural friction generates the storm that leads to freedom.

And freedom doesn't always come immediately. Often, the quest for freedom brings about great calamities. That is what the dispute is about. But if we look at our history, we will see that at every important historical junction we chose Mordechai's path.

At the end of the Talmudic story, Yossi dies, and upon returning from his funeral the Romans discover Haninah studying Torah and gathering an audience "with a scroll in his lap."

As punishment, the Romans burned Haninah at the stake together with the Torah scroll. Before he died, he said to his daughter: "I should indeed despair were I alone burned; but since the scroll of the Torah is burning with me, the power that will avenge the offense against the law will also avenge the offense against me."

He added that his death will not have been in vain, even if it may not appear that way. He said that future generations will surely vindicate the idea for which he gave his life.

His heartbroken disciples then asked: "Master, what seest thou?" He answered: "I see the parchment burning while the letters of the law soar upward."

The body may burn, but the spirit remains invincible. It will be resurrected at the conclusion of a long, historical process in the form of a national body, and the letters will join back together into a new book – our book of life.