Countless words have been written about hell. Usually descriptions include pits of fire and malevolent fallen angels who have their way with the damned souls. But when Ricky Yaakobi, 81, describes the hell she endured as a child during World War II in Greece, she describes a place full of benevolent souls.

"Every time the Germans raided the village, the partisans would ring the church bells and send one of the local kids to take us to a cave in the mountains. The kids would cover the mouth of the cave with branches so that we wouldn't be discovered. I don't remember it as being traumatic. I don't remember being afraid. I only remember the piece of sky that I could see between the branches," she says.

It is 2 p.m. in Kryoneri, a small village in Corinthia, Greece. Today, 74 years after Greece was liberated from the Nazis, two people are being honored posthumously with the title of Righteous Among the Nations, reserved for non-Jews who helped rescue Jews in World War II.

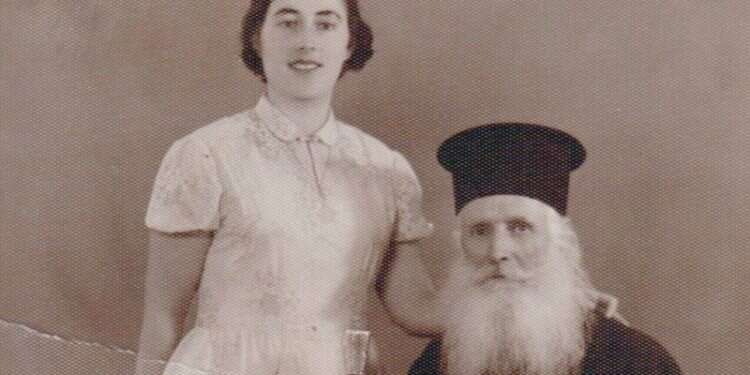

One of them is Father Nikolaos Athanasoulis, who saved the lives of Ricky Yaakobi and her family. The other is Athanasios Dimopoulos, who hid the family in his home. The honor was being accepted on their behalf by nine of their descendants.

This small, isolated town, known as Mergeni during the war, seems not to have changed a bit over the years. It has the same small houses, surrounded by flowers, the same narrow alleyways overlooking the fields and the mountains, greenhouses, a tavern and one grocery store that is actually closed most of the day. The spring that provided all the water the residents needed during the war still flows through the center of town. It is smaller now that the homes have indoor plumbing, but every now and then someone still walks up to fill up a bottle for the road.

The residents earn their living mainly from vineyards and olive groves, making raisins and olive oil, just as they did then. Today, they are gathered in a small square next to the local culture center, wearing their Sunday best. They are greeted by Greek and Israeli flags waving side by side. People from nearby villages are also arriving, and the square gradually fills with people – Ricky Yaakobi's now elderly classmates from their makeshift wartime schoolhouse gather alongside youngsters who heard the moving story from their parents.

There are also dignitaries: Israeli Ambassador to Greece Irit Ben-Abba, German Ambassador to Greece Jens Plötner, the district president, the local chief of police, the local priest. They all came to meet the little girl whose family was saved here, and who, after the war, migrated to Israel and built a kibbutz and had 10 children of her own.

Ricky was born in Athens to the Kamchi family. In 1943, when she was 6, the Germans seized the area from the Italians and her life turned upside down in an instant. Until then, she had been a spoiled child in a wealthy household with a servant who removed her father's shoes for him when he returned home from work each day. Suddenly, she had to flee with her family in a horse-drawn carriage to a village without electricity or running water. They had to hide there until the end of the war, living a modest life under assumed identities and depending on the kindness of locals for survival.

Yaakobi remembers vignettes from that time.

The first memory: "It's the era of Italian rule, before the German occupation. There was famine in Athens, and my mother, who was newly pregnant, went to get a pasta maker from a neighbor. Because of the weight of the machine, she fell down the stairs and was taken to a hospital. There she suffered a miscarriage without any anesthesia, because all the medication was sent to the frontlines. It was a miracle for the family because had a baby been born, they never would have been able to hide him in the cave without being caught."

The second memory: "My brother, mother and I were getting ready to go on vacation to a resort in November 1943, just as we did every year. My father would be joining us on the weekend. Then, suddenly, I was told that we were going to a village. A horse took us to the village on an unpaved, steep path. We traveled for hours. To this day, I don't understand how the horse managed to climb that incline."

The third memory: "We arrived at a small house in the village at 2 a.m. My brother, Yechiel, who was two years older than me, my parents Avraham and Shulamit, Uncle Rephael and my grandparents, Yechiel and Rebecca, and me. The people inside had never met us. They opened the door and let us all into their small home and gave us soup as if it were the most natural thing in the world."

Ricky has been retelling these memories for years. At first, she told her own children the stories of the kind people who saved her family. When the children grew up, her grandchildren started inviting her to their schools to tell her story to their classes. To this day she earnestly believes that it is her duty to tell the story of the courageous people in that village and relay everything she had learned from them.

Now she is here, with her 10 children, 30 of her grandchildren, and other relatives. Rina Geva, 40, her ninth child, says that when she was young she did not even realize that her mother was a Holocaust survivor.

"We knew that she fled, we heard the stories and knew all the details, but they were all adventure stories with a happy ending. It was only eight years ago that I finally understood," Geva says.

"I was studying drama therapy at the time. The girls in the class started talking about breastfeeding. I said that when I breastfed my children I always thought about what I would have done in the Holocaust, how I would have nursed my children. I talked about it as a kind of universal experience. I was sure that all nursing mothers think about where they would hide their baby if a war breaks out and how they would calm them if they were to cry in the hiding place.

"All the eyes in that room went wide. It became totally silent. Then the instructor said to me, 'Oh, you're second generation [Holocaust survivor].' And I argued with her. I said, ' I'm not.' My mother? Everything was fine with her. She always said she didn't suffer, that she didn't experience any trauma.

"That was the first time I realized that I was, in fact, a second-generation survivor. I understood the many indicators that reflect my being a second-generation survivor. I suddenly understood why it was absolutely forbidden to indulge in our home. Indulgence was a curse. Everyone always had to work. Hard. I understood that my mother, who grew up in an indulgent household as a child, suddenly lost everything in the war. That's why it was forbidden. I ultimately did my master's thesis on elderly Holocaust survivors. It was a kind of closure for me."

Dimitris Dimopoulos, 82, and his brother Georgios, 88, were children when their parents evacuated them from their treehouse to make room for the Kamchi family. They moved into a small adjacent room. Dimitris still lives in that home to this day. Today, the two brothers are accepting the Righteous Among the Nations honor on behalf of their father.

"I would take Ricky and her family back to the cave when the Germans came," Georgios recalls. "They would stay in the cave for a day or two, until it was safe, and then a kid would be sent to the cave to tell them that it was safe to return to the village."

Ricky converses with him in Greek. She tells him how one night, when she was very sick, her mother refused to take her to the cave.

"She insisted on staying at home with me. That night, the Germans looked for weapons that the partisans had hidden in the village. They burned down the barn that was next to the house. I remember standing at the window and watching the barn burn."

"Right," Dimitris confirms. "Your mother and my grandmother ran with jugs and pots to the spring and brought back water until they managed to put out the fire. Half the barn burned down. If they had known that you were Jewish, they would have burned down the whole house. Incidentally, we remodeled the house exactly in the way that it was."

Ricky: "I also remember that a German man entered the house and asked my mother what she was doing there. He recognized that she wasn't a villager. She told him that I was sick. He looked at me, and then he touched my forehead. I could see in his eyes that he didn't believe her. That he knew who we really were. But he signaled to his friend that there was nothing there, and they left. Even in hell, there was a German with a good soul. He didn't turn us in."

Avi Yaakobi, Ricky's eldest son, 57, wrote a book about the family with his brother Ido six years ago. In the book, they included several of their mother's stories.

"As kids, we mainly heard romantic stories. It is only now, that we're here and meeting these people face to face, that I can begin to understand the risk that they took. I'm trying to imagine my grandmother living here with the mothers of the women around here. When I meet them, it surprises me to learn how important our story is to them. It is a part of them no less than it is a part of us."

Ricky strolls around the village with her family. When they arrive at the church, she recalls the difficult times that are etched into her memory.

"On the Sunday after we arrived, my father went to church because our papers said we were Christian. The priest, Father Nikolaos Athanasoulis, asked him to leave.

"My father walked out but remained behind the door. He heard the priest tell the congregants, 'Everyone knows that a family from Athens has come to the village. They say they are Christian but we all know they aren't. The Germans will come and they will offer you a sack of sugar or flour to turn this family in. I am warning you that if anyone talks about them, I will burn down their house. There will be no snitches in my village.'"

The current priest is hearing this story for the first time, and it visibly moves him.

"His spirit remains in the village to this day," he says. "He hugged every stranger who arrived. We even gave the Albanians food and clothes and a place to sleep."

Besides being the town priest, Athanasoulis was also the teacher. Ricky remembers how he would clear out the pews after Sunday services and replace them with small chairs so he could teach the multi-aged group once the partisans took over the village school. She and her brother joined the makeshift class. Ricky sat with the younger children in the first row and Yechiel sat a little behind her. The priest adjusted the lessons to cater to the needs of each child's age and level.

"One day, after school, the priest left and it was just us, the children. Suddenly everyone surrounded my brother Yechiel, took a glass bottle and threatened him, 'We'll kill you just like you killed Jesus.'

"I stood there, frozen. I didn't know what to do. One kid ran out to the priest and told him what was happening. The priest came in and put the kids who threatened my brother on one side of the room and the kid who went to get him on the other side. 'These are the bad kids,' he said, 'and this is the good kid.' He punished the bad kids and sent them to the basement. His message was clear and sharp. Everyone understood.

"Every man is born with some bad in his heart. I think that God did that so that we would learn that we are capable of overcoming the bad part. The people here in the village taught me, when I was 6, that it is possible to overcome the bad part and prevail."

Father Athanasoulis had 10 children too. His youngest daughter, now 97, could not make it to the ceremony, but his grandchildren are there to accept the award on his behalf. One is Aliki Athanasoulis, 79. She approaches Ricky and hugs her.

"We were true friends," she says with great emotion.

"I remember playing together. My grandfather used to say to us, 'You need to protect this family.' You were a part of our family.

"One day your brother Yechiel was sick when they smuggled you to the cave. My mother told your mother to leave him with us, because my father was also sick. They laid in bed together and told me to call Yechiel 'my brother.' When the Germans came, they asked my mother who the child was and she said, 'My son.' Yechiel continued to call her, 'Mama, mama,' for a long time after that."

Aliki opens her purse and takes out a few mementos she had kept from Ricky's parents.

"Several years ago, I approached the Israeli Embassy in Athens because I wanted to find you. But they told me that there are a lot of Kamchi families in Israel and that they wouldn't be able to locate you."

Yechiel Kamchi died two years ago. He did not live to see this joyous day. His daughter, Meital Kamchi-Froman, 42, did not know her father's stories.

"He was the smartest man I have ever met. He understood people. He was very intellectual, always knew the right thing to do and how to help. He never thought of himself as someone who endured the Holocaust. Though he never spent any money on himself and would never throw out a cucumber, even after it rotted.

"He viewed Ricky's memories as folk tales. He thought that she was imagining. He didn't believe that what had happened in Greece had shaped his reality. But when I hear the stories, and realize how real it actually is, it explains the sense of duty that always coursed through his veins. He was an Israeli spy, and he worked in a wide range of positions. To this day we can't talk about the things he did. In the 1960s, he was sent on missions in Greece. I assume that his familiarity with the culture and the language helped him do his work."

Kristos Pangos, 88, joins the conversation. As a child, he lived with his parents in the apartment above the Kamchi family.

"When you went to the cave, we would hide your uncle, Rephael. He had a limp and couldn't walk all the way to the cave."

Ricky is visibly moved by this story. She knew that Rephael, her father's brother, who had suffered a leg injury from a street car before the war, made a notch in his walking cane every time Ricky and the family hid in the cave during a German raid. That year, Rephael made 17 notches in his cane.

Gaby Kamchi, 69, Rephael's son, was born after the war. He heard from his father stories laced with fear and terror at the thought of being caught. Now, he is trying to gather more details about the families that hosted his father during these difficult times.

Nikov Spiros, 85, another neighbor who lived on the same street, tells him how his father used to visit them because they had an English typewriter, and Raphael used it to write letters. To whom? That remains a mystery.

Ricky is warmly embraced by the chairman of a local environmental group. He was born after the war, but when the Yaakobi family approached him, he started asking about them among his parents and the older neighbors at the café.

"Everyone remembered the family," he says. "I was surprised, no one ever told us that story before. I think that it is very important to tell the story to the younger generation, to teach them to be proud of what their parents had done and to encourage them to follow the same path."

Today, anyone who wants to visit the cave needs get through thick shrubbery. Before the ceremony, the environmental group made sure to clear the path so that a delegation could revisit the cave. They plan to bring young volunteers to the area to build a commemorative site with paths, benches and signs leading up to the cave "so that the story will be told every day and never forgotten."

Surrounded by family and local schoolchildren, Ricky makes her way to the cave. There, in speaking in Hebrew and Greek, she tells a story. "One day, my father took my brother and me to a distant place. He put a white sheet over his head and explained Yom Kippur to us. Then he prayed. It was important to him that we remember this day, though he probably didn't know for sure that it was that day. He probably just decided that this day was Yom Kippur. Sort of."

"Finally he told us 'children, when the war ends, we are going to Eretz Israel.' He always wanted to make aliyah to Israel, but during our time in that village, he understood that it was really imperative."

"When the war ended, on our way back to Athens, my father stopped at the Corinth Canal. He tore up our forged documents and said 'you will never live under a false identity again.' He vowed that he would do everything he could so that we would go to Eretz Israel as quickly as possible."

"Our house in Athens had been taken over by refugees. We moved into my grandmother's apartment, my mother's mother, who had hidden in a cellar in Athens. My father nagged the British Embassy constantly for us to get our immigration certificates. He was there every week. They kept telling him that there were no visas."

"Until one day, in 1945, the Jewish Agency rounded up 200 orphan children aged 4 to 14 to take them to Israel. They needed someone to accompany them on the ship, and no one in the agency spoke any Greek. They remembered that nag, Kamchi, and asked him if he would be willing to do it. He said of course, but only with the family."

"When we got to Eretz Israel, my parents went to the immigrants' home and Yechiel and I went with the orphans, who were distributed to the kibbutzim. We ended up in Ein Vered."

Ricky concludes her story with a message to Israelis. "If one of my children or grandchildren were to emigrate from Israel, I wouldn't be able to take it. We have a wonderful country, even if there is still a lot of work to do. If you think things need fixing, get up and fix them. You, young people."

Uri, Ricky's 11-year-old grandson, plays Hatikva on the trumpet. The sounds echo throughout the entire valley.

It's 3 p.m. The square is filled with hundreds of guests. The guests are ushered into the cultural center and it, too, fills up quickly. The curious guests forced to remain outside the hall listen to the ceremony on loudspeakers placed outside. Everyone huddles at the windows to get a peek inside.

Angaliki Athanasoulis, another of the priest's grandchildren, sings the Ballad of Mauthausen in Greek and there isn't a dry eye in the crowd. The Israeli ambassador presents the award to the descendants of the two honorees and it is clear to all in attendance that they are representing an entire village of kind, courageous people.

Ricky takes the stage, her emotions apparent. She tells the audience again of the bravery that the honorees displayed. She says they didn't only give her life, they also shaped her life. She embraces the descendants of the people who saved her, and they, in turn, give her photos.

"If your parents hadn't done what they did, I wouldn't have ten children and 40 grandchildren," she says. "There would be no Ricky."

Before returning to Israel, the Yaakobi family stops at the priest's grave in the outskirts of the village. Ricky calls her grandchildren over to lay flowers on the gravestone of the man to whom they owe their very existence. Ricky's husband says "I want to thank you, Father Athanasoulis, for doing what you did, at great risk not only to yourself but to your family and perhaps to the entire village. You risked everything you had. I wish I could be sure that I would do the same if I were in your position."