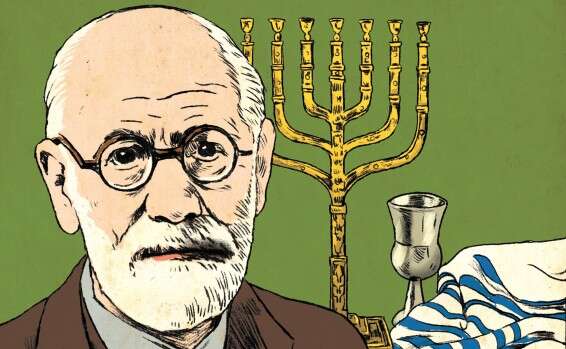

One of the only Jewish ceremonies that Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis (whose Hebrew name was Shlomo) observed was the Passover Seder. Freud knew Hebrew, so he read from the Haggadah. His wife, who came from an observant family, certainly knew the Haggadah by heart. His children, who were given a German education, apparently needed it translated into German. In short, it was a typical Seder for Jewish families who had left the ghetto and were in the process of emancipation, having ceased to keep the commandments but who maintained certain links to their Jewish past.

Freud was born a Jew, and repeatedly declared that he remained a Jew – a Jew without a God, but a Jew. That is how he self-identified his entire life, even in the face of rising anti-Semitism. But what was his Jewish identity?

His attitude toward all religions was negative, calling them a collective neurosis, but he believed in the power of myth and ascribed particular importance to Judaism's choice of monotheism. On the other hand, the stronger the Nazis grew in his spiritual homeland of Germany, the stronger Freud's Jewish identity became, along with his loathing of anti-Semitism, which he believed was very common among Christian peoples.

Freud's eldest son, Martin, wrote a memoir about life in his father's home. Judaism has a negligible place in the book. One of the stories from Martin's childhood illustrates this: He describes how only when his devout grandmother would visit the family on Shabbat did the children hear their father chanting prayers. Martin notes that this was a strange sight in the Freud household, because Jewish texts and melodies were usually absent from it.

An entire body of literature has been written about Freud's Jewish identity and the question of whether psychoanalysis is a form of Jewishness without god, like its founder. In his book "Freud in Zion: Psychoanalysis and the Making of Modern Jewish Identity," the psychoanalyst Eran Rolnik describes and parses this debate, which grew more intense after a group of Jews who belonged to the "hard core" of psychoanalysis in Germany and Austria made aliyah. One must also research Freud, the man, to understand how he saw Judaism – without God and without religion.

Freud's connection to Jewish things is clear – he grew up in a religious but liberal home, learned the Bible like all Jewish children, absorbed Jewish folklore and married a woman from an Orthodox Jewish family. These ties are not emphasized in his writing, with the exception of his book "Moses and Monotheism." However, his Jewish background also appears in his letters, in which he employed Yiddish expressions. On his 35th birthday, his father gave him a German translation of the Bible which he inscribed "To my dear son Shlomo," using literary Hebrew filled with references to Jewish sources. We can assume the father knew his son would be able to understand it.

Freud's attitude toward religion was uncompromising. He forced his observant wife to abandon her faith and her traditions. If she wanted to be with him, she would have to cut ties with her religious family and Judaism. Freud even went so far as to demand that she not fast on Yom Kippur, arguing that she was too thin to fast.

On the other hand, he sometimes did what she asked. He celebrated Purim, the Passover Seder (it would be interesting to know what he thought as he read the religious text of the Hagaddah, if he read it), and apparently observed the Yom Kippur fast. He was, of course, circumcised, and had his sons circumcised.

Moreover, two of his sons were members of prominent Zionist youth movements. Although not a Zionist himself, Freud supported their Zionist activity and was made an honorary member of the Zionist organization Kadima ("Forward"). From time to time some hidden Zionist instinct would apparently break out. In principle, he rejected the nationalist idea and fears that a Jewish state would come under the influence of religion. His close friends were Jews and he was afraid that psychoanalysis would be denigrated as a "Jewish science." For this reason, he tried to bring the non-Jewish Carl Jung into his circle until the two fell out and cut ties.

Freud's organizational links to the Jewish world became clear when he joined the Viennese branch of B'nai B'rith in 1897, the same year that anti-Semitism in the city scored a major victory when Emperor Franz Joseph approved the election of anti-Semitic leader Karl Lueger as mayor of Vienna, having rejected Luger four times since 1885. The popular Lueger represented the unapologetic anti-Semitism in a city where Jews played an important part.

But Freud also encountered veiled anti-Semitism, which may have been why he wasn't given a professorial position at the University of Vienna and and could have prompted his non-Jewish colleagues to reject his revolutionary ideas. This is the atmosphere from which Freud was seeking refuge when he joined B'nai B'rith. He also found a curious audience that was willing to discuss his opinions. Freud did not limit himself to professional lectures at B'nai B'rith; he was also an active member, at least in his first years, and actively worked to expand the chapter and recruit Jewish friends to the organization.

Freud must have understood the Hebrew name of the organization ("Allies"), which was a branch of the organization founded by German Jews in the U.S. Its goal was to create a social framework for Jews who did not hide their Jewishness, and who embraced humanist, universal enlightenment.

Freud had no difficulty reconciling his activity with an international Jewish group with his loyalty to pre-Hitler German culture, but there is no doubt that he was influenced by the rise of anti-Semitism, and the pleasure he took in his involvement with a Jewish group indicated how at home he felt among other Jews. In this context, it is interesting to note that an important part of in Freudian psychoanalysis, the family romance complex [in which children fantasize about having "true parents" of a higher social standing than their actual parents] be solved only when a person acknowledges his or her background.

How did Freud explain his Jewish identity? In a speech to B'nai B'rith members on May 6, 1926, he tried to answer this question: "That which bound me to Judaism … was not my faith, nor was it national pride. … But there remained enough other things to make the attraction of Judaism and Jews irresistible – many dark emotional forces, all the more potent for being so hard to grasp in words, as well as the clear consciousness of an inner identity, the intimacy that comes from the same psychic structure."

Freud, who was unafraid to probe the depths of consciousness and unconsciousness, fails here to find any scientific or rational explanation for the "dark emotional forces" that bind him to the Jewish tribe, other than noting that it was Jews who supported him and his theories when he was isolated in Vienna when he first started out.

In his last book, "Moses the Monotheism," as in his article on Michelangelo's Moses, Freud gives a scientific voice to "godless Judaism." He hinted as much in his speech at B'nai B'rith: "Because I was a Jew I found myself free from many prejudices that hampered others in the use of their intellects; and as a Jew I was prepared to take my place on the side of the opposition and renounce being on good terms with the 'compact majority.'"

He is not talking about dark emotional forces here, but giving a historical explanation that he developed further in his book on Moses, which encountered harsh criticism, mainly because of the three factual determinations Freud makes in it: that Moses was an Egyptian prince who learned monotheism from the Egyptian monotheist Akhenaten; that Moses was murdered by the Hebrews because of his initial refusal to follow that faith; and that he was succeeded by another Moses, a Midianite. Freud then hypothesizes that the Jewish concept of the Messiah was formed from the rebel Hebrews' guilt over the murder of the Egyptian Moses.

There is no evidence to support this theory. However, the book includes a significant statement about the uniqueness of Judaism. According to Freud, the Jewish faith has left the Jews with character traits that are passed on through the generations; the religion did its job and Jews, even in the modern era, resemble their forefathers.

One notable character trait of the Jews is their spiritualism. Freud saw this quality, which is passed down from one generation to the next, as a sharp contrast to the Christianity of St. Paul, which brought mystical and polytheistic elements to the new religion. Freud even saw the Jewish monotheistic prohibition of graven images, statues and masks as a major contribution to the birth of Judaism as an austere faith based on a simplified idea of the divine. In his opinion, religion did indeed help shape the basic Jewish characteristic – spirituality that is unaccepting of any overlord – but it completed its work and Jews were now marked by qualities that their ancient religion had left them and could therefore forgo the commandments.

Without detailing all of Freud's theory about Moses and his people, there is one point that should be discussed: Freud saw himself as the heir of the monotheistic revolution because the concept of rebelling against paganism took on many forms, but its core was passed down through the generations and shaped the Jewish character. One Freudian researcher explains that according to Freud, Jewishness comprised a biological heredity of archaic memory that the Jewish people is obligated to pass on to the next generation. The researcher stresses that Freud redefined what made Jews unique: "The fact that Jews are Jews does not stem from religion or from social customs, but because they inherited Judaism in their bones."

For Freud, the story of Moses is about the return of what is repressed; the murder of Moses by the Hebrews is part of the Jews' collective unconscious and they are born with that burden, which determines their unique character. Unlike members of other religions, Jews are not exempted from that burden, even if they convert.

Rolnik also sees the matter of Moses' identity as secondary to the moral message of Judaism, which is passed from one generation to the next: Is the question of Moses' true identity really the main issue of Freud's work? "It appears that Freud's main contribution in his work has to do with the role for which Moses was destined, to bring monotheism to the Hebrews and in [monotheism's] effect on the construction of the Jewish identity.

"The figure of Moses allowed Freud to repeat his argument that religion is not what keeps Jews separate from their Christian surroundings. The way he saw it, it was a matter of racial and intellectual differences that could not be summed up in observing the laws of the religion. These differences separate the Jews from other nations in a way that prevents [Jews from] fully assimilating," Rolnik says.

As the Nazis, who occupied Freud's beloved Vienna, forcing him to flee to London, grew more powerful, Freud grew closer to Judaism. In Hampstead in 1938, he dictated his last words to his daughter Anna. He was an old man and would eventually die shortly after World War II broke out, before the Jews of Europe were murdered – including his four sisters, whom he did not include on the list of family members allowed to go to London with him.

They remained in Vienna as easy prey for the Nazi killing machine.

Freud's remarks were intended for a conference on psychoanalysis in Paris, just before the upcoming war. Anna Freud read her father's words at the event.

"Any such advance in spirituality leads to increased self-confidence, which gives pride to people who feel that they are above those who are enthralled to the senses. We know that Moses gave the Jews the lofty sense that they were God's chosen people. The cancellation of a material form of God was a new and meaningful contribution to the people's hidden treasures. The Jews have maintained their tendency toward matters of the spirit.

"The bitter fate of the nation, politically, taught it to value its only asset that they managed to preserve, their literature. Immediately after the Second Temple was razed by Titus, Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakkai asked permission to open the first school of Torah study in Yavne. Since then, the Holy Book and the intellectual effort devoted to it have preserved the unity of the people."

This does not revoke Freud's position on the cancellation of Judaism as a religion. It is a historical explanation that sheds light on Freud's spiritual approach to his Jewish identity.

Before leaving Vienna for London, Freud sent a last letter to his son Ernst, who was in New York: "Sometimes I see myself as Jacob, taken by his sons to Egypt when he was already very old. We shall hope that after this, we will not experience another Exodus. It is time for the 'wandering Jew' to rest somewhere." In other words, at the end of his life, Freud reverted to well-known figures in Judaism: Moses, Ben Zakkai, and Jacob the Patriarch. In other words, Freud's Jewish national feeling became stronger as the Nazis stepped up their anti-Semitic persecution. And what about his attitude toward Zionism? From the start, he was ambivalent about the enterprise of Jewish nationalism. He willingly allowed himself to be named a member of the steering committee of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

In 1935, when it became clear what the Nazis intended to do, Freud wrote to Leib Yaffe, former director of the Jewish National Fund, "I know very well what an important and welcome tool this fund has made it its attempts to found a new home in our forefathers' ancient land. This is a sign of survival, a desire that cannot be overcome, that thus far has withstood thousands of years of harsh oppression! Our young people will continue the fight."

On one hand, Judaism is rejected as a religion, along with the acknowledgment that it has conferred on the Jews a non-sensual spiritual dimension, even when they abandon the religion. Hidden within this approach was growing a special feeling for Zionism, the movement for a national home for the Jews.

If we add his faith in the historical superiority of Jewish monotheism, to his tribal, nostalgic connection to his Jewish background and his increasing nationalist feeling given the hatred of Jews in Germany and Austria and the early success of the Zionist enterprise, we get a picture of Freud the Jew, in the grip of and part of Freud the universalist.

Freud is one of the only godless Jews who left the ghetto who tried to explain the bond between non-religious Jews in rational terms. But his explanation for this, too, is problematic. If the Jews passed on their spirituality via their simplified faith, how could it be passed on to non-believers? And how would they preserve their advantage in a secular humanist world? It's possible that Judaism's national meaning explains this contradiction in Freud's approach toward his Jewish identity.

Freud was the result of the emancipation of Jews and its failure. The enlightenment did not eradicate anti-Semitism, and in short order a new form of anti-Semitism – biological and racist in nature – which the Nazis embodied in the most terrible form. Alongside that tragedy, it is clear that the combination of modern thinking and existence and the Jewish identity, as Freud saw it, created a man who would have one of the greatest influences on human consciousness in the modern age.

As philosopher Yirmiyahu Yovel concludes, Freud was a non-religious Jew, a heretic, but nevertheless a Jew. This is how he saw himself and how others – Jews and gentiles, especially the Nazis, who burned his books and forced him into exile in his old age – saw him.

Freud passed away at his Hampstead home. He asked his doctor to release him from the torture of cancer. He committed suicide before the Wannsee Conference, but after reports began to arrive about the murder of Jews in Poland. He died on Yom Kippur and we will never know if there was a "Jewish element" to the fact that he committed suicide on this particular date.